Remembering Dorothy Day

Remembering Dorothy Day

By Robert Ellsberg, 7/21/11 08:19 AM ET

…

I met Dorothy Day in the fall of 1975 when I was nineteen. I had taken leave from college and made my way to the Catholic Worker headquarters in New York City, drawn by a number of motivations. I was anxious to learn something directly about life, apart from books. I was tired of living for myself alone and longed to give myself to something larger and more meaningful. But mostly, I think, I was drawn by the hope of meeting Dorothy Day, the movement’s legendary founder, and still, at 77, editor of its newspaper. I had planned to stay a few months, but was pretty quickly hooked, and remained for five years — as it turned out, the last five years of Dorothy’s life.

Our first meeting occurred on the first floor of St. Joseph House, the large room that served as soup kitchen, meeting hall, or chapel, depending on the occasion. Dorothy, who dressed in donated clothes, took pride in the occasions when she was mistaken for one of the homeless women on the Bowery. But there was no mistaking the authority she carried, even among the down-and-out characters who made up the Catholic Worker family.

To be honest, I was initially intimidated. Knowing the importance of first impressions, I had spent a lot of time preparing to ask just the right question. But when the moment came, all I could think of was, “How do you reconcile Catholicism and anarchism?” She looked at me with a bemused expression and said, “It’s never been a problem for me.”

I withdrew to ponder that for a while, wondering if her words contained some deeper meaning. Over time I came to realize that Dorothy just wasn’t too interested in abstractions.

She was actually a very social and approachable person. She had little taste for solitude and it wasn’t hard to get to know her. A great storyteller, she could spin fascinating tales about the Catholic Worker, her comrades in the radical struggle, or poignant details from the life of Chekhov, Tolstoy, or St. Therese. She was, in turn, endlessly fascinated by other people’s stories — where they came from, what books they liked, where they had traveled. “What’s your favorite novel by Dostoevsky?” was a favorite conversation starter. Whether you answered The Brothers Karamazov or Crime and Punishment, she inevitably endorsed your selection.

A year after my arrival Dorothy asked me to become the managing editor of the Catholic Worker paper. She was, as she liked to say, “in retirement,” and the day-to-day management of the paper and the household were in the hands of those she called “the young people.” I was twenty. My “promotion” had very little to do with any qualification for the job and everything to do with the fact that no one else was particularly interested. But Dorothy had faith in people and she was able to make them feel her faith as well, so they forgot their feelings of inadequacy and found themselves doing all kinds of things they never dreamed possible.

She didn’t much like the rather lugubrious art I selected for my first issue of the paper. “People my age don’t want to see dark things like that,” she said. “They want to see cheerful things, like the ocean, or the circus.” Otherwise she exercised little day-to-day oversight. Each month she would give me a few sheets of entries typed up from her journal. “Do what you want with it,” she would say. “I don’t care if you change it, cut it up, or throw it away.” From previous editors I learned that she was not always this detached about her writing. Part of the reason for writing now, she said, was to let her readers know that she was “still alive.” Indeed, if she missed a month, we would be besieged by letters inquiring as to her health.

Dorothy admired hard workers. In the “war between the worker and the scholar,” she liked people to be both. She didn’t particularly admire those who were just “scholars,” who sat around reading all the time. She thought that men were constitutionally prone to this kind of abstraction, which was responsible for many of the world’s problems. (Certainly my own tendencies were in that direction.)

Nevertheless she enjoyed talking about ideas, especially as they were embodied in history, novels, social movements, or in people’s lives. It was Dorothy who first sparked my fascination with the lives of the saints–both canonized figures like St. Francis and Teresa of Avila, and other holy people like Gandhi, Cesar Chavez, and Martin Luther King. She delighted in talking about their human qualities, as much as their heroic deeds. “Youth has an instinct for the heroic,” she liked to say. And even as she grew bent with age and hard of hearing, she retained her idealism, an instinct for adventure that connected her in a special way with the spirit of youth.

One day I applied under the Freedom of Information Act for a copy of her voluminous FBI file. It documented the efforts of the FBI over several decades to comprehend just what category of subversion the Catholic Worker was supposed to represent. Apparently at one time Dorothy’s name was placed on a list of dangerous radicals to be detained in the event of a national emergency. What particularly pleased her, however, was a profile that J. Edgar Hoover had composed: “Dorothy Day is a very erratic and irresponsible person who makes every effort to castigate the Bureau whenever she feels inclined.”

“That’s marvelous!” she said. “Read it again!”

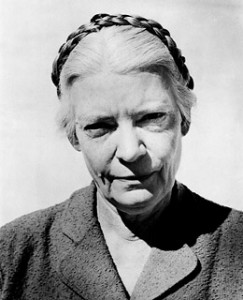

There was a playful side to her. Photographs tend to make her look severe. But what stands out in the memory of anyone who knew her was her girlish laugh and sense of fun. Many of her stories were self-deprecating — such as the time she knitted a pair of socks and one of the women in the house asked if she could have them to use as a “gag gift” for Christmas. Or the time in the 1950s when she read a book about Chairman Mao and volunteered to lead a talk at the next Friday night meeting. “Well, somehow word must have spread because that Friday the room was filled with people from Chinatown and scholars from the University, and they must have been surprised when all I did was stand up and give a book report. You see,” she said, “I’m such a fool that I’m never afraid of appearing foolish.”

All the same, she was fastidious and cultivated in her tastes; she loved classical music, the opera, literature, flowers, and beautiful things. In her old age she liked to surround herself with postcards: icons and paintings, but also pictures of nature — trees, the ocean, arctic wilderness. She loved to quote Dostoevsky’s words, “The world will be saved by beauty.”

Despite all the sadness and suffering around her, she had an eye for the transcendent. There were always moments when it was possible to see beneath the surface. “Just look at that tree!” she would say. It might be an act of kindness, the sound of an opera on the radio, or the sight of flowers growing on the fire-escape outside her window: such moments caused her heart to rejoice. She liked to quote St. Teresa of Avila, who said, “I am such a grateful person that I can be purchased for a sardine.”

Above all she was a woman of prayer. She attended daily Mass, when she was able; she rose at dawn each day to recite the morning office and to meditate on scripture. After years of reading the breviary the language of the Psalms had become her daily bread: “Sing to the Lord a new song … sing joyfully to the Lord.”

When I went to the Catholic Worker I was not motivated by explicitly religious interests. Like Dorothy, I had been raised in the Episcopal Church, but I had pretty much drifted away from organized religion. What drew me to the Catholic Worker was Dorothy’s lifetime of consistent opposition to war, and the fact that her convictions were rooted in solidarity with the poor and those who suffered. Ultimately, I came to appreciate not just Dorothy’s anti-war convictions but the deeper tradition and spirituality that sustained her. I understood nothing about Dorothy if I didn’t realize the importance of the sacraments, prayer, liturgy, and the communion of saints, in which her witness was rooted. When I understood that, I felt a need to become a Catholic myself.

I was received into the church in a small chapel in a tenement apartment of the Little Brothers of the Gospel. Dorothy greeted me afterwards with much joy, giving me an old biography of Charles de Foucauld and a cross made out of nails. “No one will dare to arrest you as long as you’re wearing that,” she said.

She recalled the occasion of her own first communion in a church on Staten Island, many years before. “I was all flustered with the occasion and I said to a woman, ‘Oh, I must get home. I’ve got a baby to feed.’ And the woman said, ‘Why, I didn’t know you were married.’ And I said, ‘I’m not.’ And you should have seen the expression on her face, wondering whether they hadn’t made a terrible mistake!”

It was one of our last conversations. That fall I returned to college. So many volunteers over the years had come and gone. She wished me well and urged me not to forget her. “What is your favorite book by Dostoevsky?” she asked. “The Idiot,” I suggested arbitrarily. “Mine too!” she replied with delight.

She died soon after, on November 29, 1980.

That was over thirty years ago. After her death I would have been delighted to see Dorothy immediately canonized and named the patron saint of peace and social justice. From a distance of three decades, however, I see that she was more than a hero for radical Catholics. At a time when the church is so greatly divided between ideological factions, Dorothy was truly a saint of “common ground” — someone who held in tension a great love for the church along with deep sufferings over its sins and failings.

I think about her especially in these times we are living through, when once again the gospel narrative seems somehow foolish and irrelevant in the face of terrorism and endless war. Once again we confront a situation in which massive violence is proffered as the only realistic solution to our problems, and a “just cause” is invoked to justify virtually any means.

I remember sitting with her over supper while a somewhat deranged young man pounded on the table insisting, “Dorothy, you just don’t understand. Individuals in this day and age are not what’s important. It’s nations and governments that are important.”

“All individuals are important,” Dorothy answered, in a quiet voice. “They’re all that’s important.”

But she was equally discerning in her approach to peacemaking, cautioning against the temptation to be overly concerned with “success.” Too often, she believed, would-be peacemakers are driven by the need to be heard in the corridors of power, to be impressive and spectacular. But Christ’s victory, she always noted, was achieved by the way of apparent failure: “Unless the seed falls into the ground and dies, it bears no fruit.” “We do what we can,” she often said. Nevertheless, “We must always aim for the impossible; if we lower our goal, we also diminish our effort.”

One of her favorite characters was Pietro Spina, the hero of Ignazio Silone’s novel, Bread and Wine, who does no more during a time of war than go out in the night and write the word NO on the town walls. If nothing else his deed shatters the “unanimity of consent”; it allows people to envision the subversive possibility of an alternative reality.

Dorothy was a great believer in what Jean-Pierre de Caussade called “the sacrament of the present moment.” In each situation, in each encounter, in each task before us, she believed, there is a path to God. We don’t need to be in a monastery or a chapel. We don’t need to become different people first. We can start today, this moment, where we are, to add to the balance of love in the world, to add to the balance of peace.

…

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/robert-ellsberg/dorothy-day_b_904964.html or http://huff.to/r2GLte or http://tinyurl.com/427sz9l

AP photograph: http://www.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,1850894_1850895_1850863,00.html or http://ti.me/roYF4a or http://tinyurl.com/yl4vote