Jimmy Carter: ‘We never dropped a bomb. We never fired a bullet. We never went to war’

Jimmy Carter: ‘We never dropped a bomb. We never fired a bullet. We never went to war’

By Carole Cadwalladr, Sunday 11 September 2011

…

Where does Jimmy Carter live? Well, close your eyes and imagine the kind of house an ex-president of the United States might live in. The sort of residence befitting the former leader of the most powerful nation on earth. Got it? Right, now scrub that clean from your mind and instead imagine the sort of house where a moderately successful junior accountant and his family might live.

It’s what in America is called a “ranch house”, or, as we’d say, “a bungalow”. There are no porticoes. No columns. No sweeping lawns. There’s just a small brick single-storey structure that Jimmy and his wife, Rosalynn, built on Woodland Drive back in 1961 when he was a peanut farmer and she was a peanut farmer’s wife, right in the heart of the town in which they grew up. Though Plains, Georgia is barely a town. A street, might be a more accurate description. A single road going nowhere much.

At the end of the drive there’s a fleet of black Suburbans, giant SUVs with blacked-out windows: not too many junior accountants would have a crack team of secret service agents on site, it’s true. But it’s hard to overstate how modest it is. It’s not much of an exaggeration to say that the whole thing would fit comfortably into the sitting room of just one of Tony and Cherie Blair’s nine houses.

If you’re under 40, you may not even remember Jimmy Carter. But you might recall President Bartlet. From The West Wing. When I chat to Phil Wise, vice-president of the Carter Center – the foundation Carter set up after leaving office – he reminds me that Martin Sheen partly based his character on Carter. Wise grew up next door to the Carter family, and as a college student he volunteered for the governor’s campaign alongside Chip, the middle son. He worked for the presidential campaign “as the youngest gopher”, and ended up in the White House as Carter’s appointment secretary. (His character in The West Wing? “The African-American man who sits outside the president’s office.”)

Was Carter really like President Bartlet? I ask Wise that question as we drive from the Carter Center in Atlanta to Plains through the rolling Georgian countryside, passing signs for catfish buffets and churches that exhort us to “Get out of Facebook and into God’s Book”. He considers the question seriously: “They were both former governors. Could both be very stubborn. And they both had a certain moral tone.” He concludes: “There was a lot of Carter in the part.”

In Britain we assumed that a politician that upright, that pure, could only be fictitious, and the expenses scandal has only reinforced that. But everything about Jimmy Carter’s life – what he did as president, and what he’s done since – has proved that “certain moral tone”. And his home somehow encapsulates this. Inside, there’s no hallway, just a patch of carpet separating a small dining room from a tiny sitting room. Then, all of a sudden, there’s Jimmy.

Strictly speaking, he’s still Mr President, but it’s hard to give the office its true gravitas in what looks like my mum’s living room. And there’s a plain, homespun quality about him that’s reminiscent of that other great Jimmy, the patron saint of small-town American life: Jimmy Stewart. He’ll turn 87 in October, and is recovering from having both his knees replaced this summer, but the dazzling smile that once captivated America is still there. Though it’s a terrible cliché, not to mention patronising and ageist, to describe any octogenarian as “twinkly”, he undeniably is.

He leads me slowly into the family room at the back of the house. Photographs of the children, grandchildren and great grandchildren line the walls, and an old throw covers an even older sofa. Mary, the housekeeper who’s been with the family for 40-odd years, brings Carter coffee in an ancient plastic cup, so old that the “Royal Caribbean” logo on it has faded nearly clean away. (Mary first came to work at the governor’s mansion as a convicted murderer on day release, and – how’s this for living your liberal beliefs? – the Carters asked her to look after their three-year-old daughter, Amy.)

It’s a tiny place, Plains, two-and-a-half hours’ drive from Atlanta, but there was never any doubt that Jimmy and Rosalynn would come home. “Oh no. Never. My folks have been here since 1860. And Rosalynn’s folks since the 1830s, so our families have been involved with the Plains community for a long time. Our land is here, and our churches are here, and the schools that we went to are here. We have a full life here. No matter what we do around the world – and we now have programmes in maybe 70 countries – we can work from here as easily as anywhere. This is where we’ve always come back to.”

It was even more of a political Siberia in the pre-internet age of 1981 when they first returned after Carter was defeated by Ronald Reagan. Wise came with them as their chief of staff. He recalls: “I was horrified when they said they were coming back here. I had to go and live with my parents. I thought they’d at least go to Atlanta.” Thirty years on, the Carters are still incredibly involved with the town. I stay in the Plains Inn, a former funeral parlour turned into a hotel – and decorated by Rosalynn – at the Carters’ instigation a few years back. One of my fellow guests works for the national park service at Carter’s childhood home, now a museum, and tells me that the Carters still pop by to pick vegetables from the garden. And on most Sundays Jimmy wanders down to the Maranatha Baptist Church to teach Sunday school.

In the Carters’ family room there’s a Harry Potter book on the coffee table. At Christmas they’re taking the entire family to the Wizarding World of Harry Potter at Universal Studios in Florida, and “so I thought I ought to acquaint myself with Harry Potter first,” he says. He’s never been one to skimp on the homework. Wise tells me: “My entire life, I’ve only ever managed to tell him one thing he didn’t already know. I told him about how in the second world war the Japanese tried to develop a folding aeroplane, and he said ‘I did not know that.’ And I swear that’s the only time that has ever happened.”

Jimmy’s early years on the family farm just outside Plains coloured his entire life. As a boy during the Great Depression, he recalls, “streams of tramps, or we called them hobos, walked back and forth in front of our house, along the railroad”. Even more influentially, it was a mostly black community. “I learned at first hand the deprivation of both white and black people living in a segregated community, which was then not challenged at all.” Except by his own mother; thanks to her liberalism all his earliest playmates were black.

Politics was never on the agenda. He’s adamant about this, and when Rosalynn joins us she’s bemused at the idea that he had any desire to be president when she married him.

“Oh no. I assumed he’d be in the navy and I’d be a naval wife. And he did too.”

What would you have made of it had you known?

“I’d have thought it was tremendously exciting,” she says.

“But ridiculous,” he interjects.

“But totally ridiculous,” she agrees.

They’re not a couple, one senses, to shy away from stating bald truths. She’s four years her husband’s junior, and his equal in no-holds-barred energy. Until his knee operations temporarily prevented him, he swam “at least” 40 lengths a day. And she does two-and-a-half miles around the property on a trike. They travel all over the world. And Peggy, who works for the Carter Center in Plains, tells me: “Every minute of every day is scheduled. They make us mere mortals look bone idle.”

They’re also – rather amazingly, given that they’ve just celebrated their 65th wedding anniversary – still as soppy about each other as two lovebirds. Everyone tells me this. Wise, four employees at the Carter Center, a man in a shop in Plains. And Jimmy and Rosalynn themselves. “They hold hands all the time,” says Kelly Callahan, the assistant director of the Carter Center’s health programme. “They’re just so cute. It’s unbelievable. They do everything together. They come to all the staff meetings, and he’ll always say, ‘Did I forget anything, Rosalynn?'”

The story of Jimmy Carter’s rise to power is, even 35 years on, still extraordinary. He truly was the man from nowhere. What was it, I ask Rosalynn, that enabled him to achieve the highest office in the land?

“Well, he was elected governor after a long campaign…” she begins.

He interrupts her. “But what do you think propelled me from Plains to the White House?”

“Well, it was not until you were governor that you ever dreamed of being president, I don’t think.” And she continues in this vein until he interrupts her again.

“I’d be interested in hearing your answer to the question she asked,” he says. And he really is. He’s genuinely amused, and anticipating her potential reply. I get the sense she’s not one to carelessly drop extraneous compliments. And eventually, after I rephrase it, she answers: “Well, I think he was always just looking for something more to do. In the navy he always got the best job, and always went one step up, and then another step. And I think it’s in his nature to be adventurous. He’s always said, ‘If you don’t try something, you won’t succeed.’ So he’s never been afraid of failure.”

It’s not the most glowing of encomiums, all things considered, but he seems just about satisfied with this.

The thing you have to remember about Jimmy Carter, explains Steven Hochman, a Jefferson scholar who’s worked with him for the past 30 years, helping research his books, is that he’s a problem-solver by nature. “He’s very independent. If you grow up on a farm, you have to do things for yourself. When some problem comes up, he’s used to solving it. His dad would do it. He would do it.”

The young Jimmy studied engineering at the US naval academy in Annapolis, and even now he’s drawn to practical problems he believes he can solve. The Carter Center, the foundation he and Rosalynn set up to promote and champion human rights, has been quietly working towards eradicating some of the world’s nastier diseases. Guinea worm, a debilitating parasite, affected 3.5 million people worldwide when the Carter Center decided to try to eradicate it. Last year there were just 1,797 cases, mostly in South Sudan, and it looks set to be only the second (after smallpox) disease ever eliminated. Also on their hit list is river blindness, trachoma and lymphatic filariasis, otherwise known as elephantiasis. As part of their human-rights efforts, they monitor elections in some of the most troubled corners of the world. “Our basic principle that has shaped us ever since we were founded is that we don’t duplicate what other people do,” says Carter. “If the World Bank or Harvard University or whoever is adequately taking care of a problem, we don’t get involved. We only try to fill vacuums where people don’t want to do anything.”

Kelly Callahan calls the diseases “low-hanging fruit”. “All the money goes to the big three: HIV, Aids and malaria. Everything else gets neglected. But these diseases [those the Center targets] affect the poorest of the poor. And by eliminating them we can make a huge difference to the lives of the poorest people on earth. I think he was drawn to this work because he likes projects that are outcome-orientated, and that are community-based – very much like he is. And he still asks all these questions. There’s a desire to do more. A lot of us in this line of work are competitive. We want to do more. And he’s like that. He’s very passionate and intense.”

And he shows no sign of letting up. He travels to the world’s most intractable trouble spots as part of his work with the Elders, a group of elder statesmen (the caped crusaders of conflict resolution!) led by Nelson Mandela. In April he was in North Korea, trying again to negotiate an agreement on its nuclear programme – as he did successfully in 1994 when he persuaded Kim II-sung to agree to a nuclear weapons freeze. And this autumn he’ll be in Haiti, helping build 100 homes with volunteers from Habitat for Humanity, something he’s done every year for the past 30 years. He’s pioneered a model of post-presidential activism that Bill Clinton (or even ex-CEOs such as Bill Gates) have striven to emulate. And in 2002 he received the ultimate recognition for it: the Nobel Peace Prize.

Jimmy Carter approached his career with all the pragmatism of a practical man, and the deep-rooted morality of a religious one. American politics is increasingly dominated by what’s called the religious right; conservatives who share an anti-scientific world view, who treat evolution as a heretical theory, and universal healthcare as dangerous socialism. But Carter was of the religious left, a very different beast. He has a profound faith, rooted in his Baptist upbringing. He and Rosalynn read the Bible to each other every night and have done so for “30-something years”. (They read in Spanish, so that they can practise their language skills at the same time; they’re relentless self-improvers.) “I read a chapter one night,” says Rosalynn. “And he reads a chapter the next night.”

Politics wasn’t so much a life choice he made, as the culmination of a sequence of events. “I was the chairman of the school board, and I was concerned about the public school system,” he tells me. “I served as governor for as long as the constitution would permit me, and after that I ran for president in 1975. As you probably know, I was elected.”

I heard, I say. Was there really never a master plan?

“Not at all. It was always just the next step. When I told my mother I was running for president, she said, president of what?”

Ah yes, Miss Lillian. I’ve read about her. She was the great egalitarian influence of his childhood years: “She never treated our black neighbours any differently than she did white people, and she was able to get away with that in a segregated society because she was a member of the medical profession [a nurse] and she was a very strong-willed woman anyway.”

At the age of 68 she went off to be a Peace Corps volunteer. There’s a template, then, for an active old age, and he’s started to resemble her in other ways too. He was the first high-profile figure to call for Guantánamo to be closed. He has criticised President Obama for failing to live up to his promises, for backtracking on foreign affairs, for failing to keep his resolve on Israel. (“When he said no more settlements, that was a major step forward. But then he backed away from that, as he’s backed away from all of his other demands.”)

But his name is being increasingly linked with Obama’s in other contexts too. In the heavyweight journal Foreign Policy, Walter Russell Mead coined a phrase to characterise what he suggested was hampering President Obama’s presidency: the Carter Syndrome. The “conflicting impulses influencing how this young leader thinks about the world threaten to tear his presidency apart. And in the worst scenario turn him into a new Jimmy Carter.”

Or, as Nicholas Dawidoff put it in a major profile Rolling Stone published of Jimmy Carter this spring, it’s because of Obama’s “scattered ambitions, his lack of a grand vision, his outsider’s discomfort with the ways of Washington, his fumbling economic policies… and above all his supposed lack of toughness, [that] the man he is increasingly compared with is Carter”.

But as Dawidoff points out, Jimmy Carter is to Republicans what George W Bush is to Democrats: their very names make their enemies foam at the mouth. And the reassessment is working both ways. For years Carter was considered a failure because he was a single-term president, because he was perceived as weak, and because he refused to take action against America’s newly minted enemy, Iran. But, at this distance, the three great achievements of that single term seem even more of an achievement today: he forced through the Camp David Accords, one of only two peace treaties that Israel has ever signed, isolating Anwar Sadat and Menachem Begin at Camp David for 13 days until he gradually wore them down; he also forced through the Panama Canal Treaty, a deeply unpopular move that returned the canal to Panama, but which prevented, many believe, a difficult and nasty war in Latin America; and he brought in an energy policy that saw him reduce America’s dependency on imported oil by half. He was mocked – three decades before global warming became a fashionable concern – for walking around the White House, turning down the thermostats.

What he’s most proud of, though, is that he didn’t fire a single shot. Didn’t kill a single person. Didn’t lead his country into a war – legal or illegal. “We kept our country at peace. We never went to war. We never dropped a bomb. We never fired a bullet. But still we achieved our international goals. We brought peace to other people, including Egypt and Israel. We normalised relations with China, which had been non-existent for 30-something years. We brought peace between US and most of the countries in Latin America because of the Panama Canal Treaty. We formed a working relationship with the Soviet Union.”

It’s the simple fact of not going to war that, given what came next, should be recognised. “In the last 50 years now, more than that,” he says, “that’s almost a unique achievement.” He was bitterly opposed to both Iraq wars. “Iraq was just a terrible mistake. I thought so in Iraq 1, and I was against it in Iraq 2.” And it’s not just George W Bush who has blood on his hands, he says, but Tony Blair too: “I don’t know what went on in private meetings when Tony Blair agreed to it. But had Bush not gotten that tacit support from Blair, I don’t know if the course of history might have been different.”

It’s the second time we’ve talked about Blair. Money has disfigured American politics, Carter says. I ask him about the pledge he made the day after he lost his bid for re-election, when he told the press he would not make money off the back of his presidency. Is that true?

“That is correct,” he says. Then he jokes: “It was kind of a weak moment.”

What inspired it?

“My favourite president, and the one I admired most, was Harry Truman. When Truman left office he took the same position. He didn’t serve on corporate boards. He didn’t make speeches around the world for a lot of money.”

Unlike Blair, I say. He’s made a fortune since leaving office.

“I know he has. I know that.”

What do you think of that?

“I wouldn’t comment on that.”

But then he doesn’t need to. His whole life has been a comment on that.

It seems an impossibly long time ago, 1980. Prince Charles had just started dating Lady Diana Spencer. Dallas was the most popular TV show on both sides of the Atlantic. And Iran had recently been convulsed by the world’s first Islamic revolution. More pertinent to the story of Jimmy Carter, Islamist students and militants had stormed the American embassy in Tehran in November 1979 and taken 52 members of staff hostage.

What could the US do? How could it save the hostages? It was a question that President Carter wrestled with for 444 long days. It paralysed the presidency. Carter refused to campaign for re-election, refused to light the White House Christmas tree, refused to bomb Tehran.

Rosalynn has been quoted as saying that, had her husband bombed Tehran, he would have been re-elected. I put this to Carter. “That’s probably true. A lot of people thought that. But it would probably have resulted in the death of maybe tens of thousands of Iranians who were innocent, and in the deaths of the hostages as well. In retrospect I don’t have any doubt that I did the right thing. But it was not a popular thing among the public, and it was not even popular among my own advisers inside the White House. Including my wife.”

Really?

“Well, she thought I ought to be more willing to use military power.”

Instead, he launched Operation Eagle Claw and, in a terrible confluence of extreme circumstances involving a sandstorm in the desert and a helicopter crash, eight US servicemen were killed. And no hostages were rescued. It was a humiliating failure. A failure his political career never recovered from.

Nicholas Schmidle, in his New Yorker account of the covert Seals mission that killed Osama bin Laden in May this year, notes that: “Deploying four Chinooks was a last-minute decision made after President Barack Obama said he wanted to feel assured that the Americans could ‘fight their way out of Pakistan’.” In the event they weren’t needed (although the prime helicopter did crash in Bin Laden’s compound and had to be abandoned), but the source of his anxiety is easy to guess. If there is one thing President Carter wishes he’d done differently, it would be sending “one more helicopter”.

“We had to have six, to bring back the hostages. We planned on seven. At the last minute I ordered eight. And, incredibly, three of them were decommissioned. One turned back to the aircraft carrier. One went down in a sandstorm in the desert, and the other had a hydraulic leak and crashed. Complete surprise to all of us, particularly to the military experts. We lost three out of eight helicopters. So then we had to withdraw. But if I’d had one more helicopter we could have brought back our hostages, and I would have been looked upon as a much more successful president.”

Does that haunt you?

“Not really. I feel quite at ease with what we were able to do while I was president and what we’ve done since then.”

No regrets?

“Not really. On balance, my life has been a constant stream of blessings rather than disappointments and failures and tragedies. I wish I had been re-elected. I think I could have kept our country at peace. I think I could have consolidated what we achieved at Camp David with a treaty between Israel and the Palestinians. But I left office, and a lot of things changed. I think we would have had a very successful energy policy in this country and maybe around the world if I’d stayed in office. But that’s just dreaming. I’m willing to accept that.”

But it’s a tantalising prospect – to play alternative histories. To do a Jimmy Stewart with Jimmy Carter. The great what-might-have-been? Lots of different people tell me that the Middle East is his “unfinished business”. Including him. “My constant prayer, my number one foreign goal, is to bring peace to Israel. And in the process to Israel’s neighbours.”

The Camp David Accords were a massive political gamble. He risked failure, but he succeeded where no one has before or since. In 2006 he published a book, Palestine: Peace not Apartheid, that excited fury from the American right. Steven Hochman tells me: “He’s used to criticism. But I think it did hurt him. Some friends broke with him.” And yet it’s hard in Britain to understand what’s so controversial about the book. He recommends, as has pretty much everybody else who’s ever considered the situation, a two-state solution.

What about death? That’s what I want to ask, but it’s a bald question to ask anyone, let alone a former president who’s accelerating towards his 90s. Wise splutters when I start talking about “your time left”. I’d read, though, that Carter’s favourite poet is Dylan Thomas, and he confirms this. So I ask: “Does the poem ‘Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night‘ have increasing resonance as you get older?”

“It does. It does,” he says.

It’s one of Thomas’s most famous works, written as his father lay dying. He exhorts him instead to “rage, rage against the dying of the light”. No one, not the wise, nor the good, nor even the wild men, he writes, has ever done enough to be ready to die.

Does he think he’ll rage against the dying of the light? “I do, I do,” he says. “Come on, I’ll show you my Dylan Thomas.” He takes me off to his study – a converted car-port – where there’s a whole row of Thomas and on the wall a carefully transcribed handwritten framed copy of “A Refusal to Mourn the Death, by Fire, of a Child, in London”. “Amy did that for me,” he says. “When she was a child.” (The former First Daughter was eight when she entered the White House, grew into a student firebrand and is now a stay-at-home mother in Atlanta: Rosalynn shows me a photo of Amy’s elder son holding a baby and says, “I just love that photo. You know, I didn’t have her until I was 40, and she’s just had a baby in her 40s.”)

Does that poem also have special significance too for Jimmy?

“Not really,” he says. “I just always really loved the sound of the words. It’s so beautiful. I made all my children learn it by heart.”

He’s published his own poetry, too, along with many volumes of memoirs and a children’s book. On the way out of the room he points out his oil paintings. Some are more successful than others (he got round the tricky self-portrait issue by painting himself from behind) but he’s nothing if not a trier.

Karin Ryan, director of the human-rights programme at the Carter Center, says what she loves about him is “that he’s not jaded. He’s not cynical. He gets exasperated but he still has hope. He gets enthusiastic in a very young way. There’s almost an activist spirit about him.”

She has worked at the Carter Center for more than 20 years after happening to visit the museum. “I saw the exhibits on Camp David and Panama and was blown away. I just thought: this is the way that American power should be. It was at the height of Reaganism, and I really related to this case of America as a moral power. Of using our power and institutions for peace and empowerment. Those of us who’ve stayed, we’ve hung around because we love them, Jimmy and Rosalynn.”

Just not as much as they love each other. I find myself wondering about this. I’ve read Ronald Reagan’s diaries and observed how much he doted on Nancy; and Laura Bush’s memoirs, in which there’s no doubt that her marriage to Dubya is a strong and happy one; as, surely, is Barack and Michelle’s. A rock-solid marriage is almost a pre-condition of being elected president, it seems. But of all of them, none can match Jimmy and Rosalynn.

I mention to Carter how Kelly Callahan had spoken of him as a true romantic. Jimmy and Rosalynn both answer at once.

“I think he’s romantic,” says Rosalynn.

“I think so,” says Jimmy, and he turns to look at her. “We’re still very much in love. We miss each other when we’re apart.”

“That’s why he doesn’t like for me to go off on my own. I go sometimes but he doesn’t like it. He likes for me to be at home.”

Carter tells me he could never have become president without Rosalynn. “That is literally true. I was completely unknown, and I didn’t have any money. So I went to one state and Rosalynn went to a different state. My oldest son and his wife, my middle son and his wife, my youngest son and his wife, my mother, and my mother’s sister all went to different places every week. And they all campaigned for me. So by the time the other more famous candidates woke up, they’d already lost.”

And their secret to a happy marriage? “We give each other space,” says Rosalynn. “That’s really important. And it was most important after we came home from the White House because we’d never been at home all day together every day. And it was a difficult time.”

They’ve always made a point of learning new things together. They have their Spanish lesson once a week. They climbed mountains, learned how to fly fish, went birdwatching. “I learned how to ski when I was 59 and Jimmy was 63,” says Rosalynn.

He was dating Miss Georgia Southwestern College when they first went out. Carter explains: “The next-to-last night that I was home on vacation from the naval academy, the whole family had a family reunion, and she [the beauty queen] couldn’t have a date with me. So I was looking for a blind date, and picked up Rosalynn in front of the Methodist church.”

Rosalynn takes up the story: “His sister, Ruth, was my best friend, and we’d been trying to get me together with him all summer. That night, Ruth and her date stopped in front of the church and picked me up, and I finally got to go with him.”

So young Jimmy wasn’t sad to see the back of the beauty queen?

“Well… after I’d had a date with Rosalynn, I was not interested in anybody else.”

It was love at first sight?

“It was. For me.”

I should be asking him for his views on Michele Bachmann. Or Binyamin Netanyahu. Or Kim Jong-il. But it’s terribly affecting, watching and listening to them both together. And if President Obama does turn out to have the “Carter Syndrome”, he might just need to count his blessings. I’m really not sure they make politicians like Jimmy Carter any more. If they ever did.

…

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/sep/11/president-jimmy-carter-interview or http://bit.ly/qHy9pj or http://tinyurl.com/3q92a5k

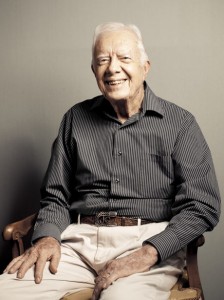

Photograph of President Jimmy Carter at home last month in Plains, Georgia, by Chris Stanford for the Observer.