Mythologizing Evolution

By Karl Giberson, Ph.D, 05/31/2012 12:09 pm

…

A prominent new atheist blogger has just completed a week-long series paying homage to the great journalist H. L. Mencken, best known for his coverage of the 1925 Scopes Trial. The series represents ongoing efforts to enhance the mythology of evolution, efforts that have been particularly successful when it comes to the Scopes Trial.

Most people today see the Scopes Trial as a simple confrontation between superstitious hillbillies who rallied around a great buffoon, William Jennings Bryan, who prosecuted a great and open-minded science teacher, John Scopes. The crime was the teaching of evolution.

Mencken was widely read and is celebrated today for his hyperbolic and uncharitable rhetoric. He ridiculed the local population in Dayton — called them “rustic ignoramuses” — in ways that no major news outlet would publish today. When Bryan died, shortly after the trial, Mencken wrote a most hateful obituary:

“It was plain to everyone, when Bryan came to Dayton, that his great days were behind him — that he was now definitely an old man, and headed at last for silence. There was a vague, unpleasant manginess about his appearance; he somehow seemed dirty, though a close glance showed him carefully shaved, and clad in immaculate linen.”

Such images serve the purposes of those that want evolution to be our creation myth. Anyone who rejects evolution must be, according to Mencken, an ignorant mangy buffoon. Or, as Richard Dawkins has stated, in language only slight more temperate, “stupid, wicked, or insane.”

Such uncharitable caricatures of the critics of evolution make it easy to dismiss their concerns. If our critics are buffoons, we can ignore them.

Bryan was certainly wrong about evolution. But he was not a buffoon; he was a champion of liberal causes and ran three times for president on the democratic ticket. We would do well to think about the concerns that animated his anti-evolutionary campaign and brought him to Dayton. Bryan was, for example, horrified at the way German intellectuals were rationalizing the militarism that would lead Germany into World War I. A professor at the University of Leipzig published a frightening book titled “Darwinism Applied to Peoples and States” in 1910, arguing that the morally advanced European races should exterminate the morally inferior ones. He called this the “righteousness of the struggle for existence” and anticipated it would lead to the “extermination of the crude immoral hordes.”

Whether or not this is an appropriate application of Darwin’s ideas — I don’t think it is — Bryan’s concern along these lines certainly deserves our respect, not ridicule, and we might learn something from pondering it.

Bryan watched developments in Europe closely and warned president Woodrow Wilson that the U.S. should not enter the war. “It is not likely that either side will win so complete a victory as to be able to dictate terms,” he wrote in 1914 after two years as Secretary of State, “and if either side does win such a victory it will probably mean preparation for another war. It would seem better to look for a more rational basis for peace.” Bryan resigned as Wilson’s Secretary of State in 1915, protesting America’s entry into World War I.

The concerns about evolution that Bryan expressed — perhaps inarticulately — represent a dark chapter in the history of Darwin’s theory that many of its champions today would like to suppress as they mythologize the story of evolution. In Bryan’s day evolution was almost universally believed to sanction draconian measures to improve our species by eliminating the less fit. The textbook from which John Scopes supposedly taught evolution — George Hunter’s “A Civic Biology” — spoke in chilling language of “parasitic” families that do harm by “corrupting, stealing, or spreading disease.” The students were warned of the importance of preventing the propagation of such a “low and degenerate race.”

This, of course, is the sordid tale of Social Darwinism — a misapplication of Darwin’s ideas that died in the Nazi death camps along with those the Nazis perceived to be from a “low and degenerate race.”

Bryan, of course, was wrong about evolution — although we might cut him some slack given the state of the theory then — and his performance in Dayton certainly had a few blunders. But we should not reduce him to a caricature to avoid confronting the reality of what evolution meant for so many at that historical moment.

In the same way, we should listen more carefully to the critics of evolution today. Not all of them are stupid, wicked or insane.

…

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/karl-giberson-phd/mythologizing-evolution_b_1546356.html?ref=religion or http://huff.to/L4UG7k

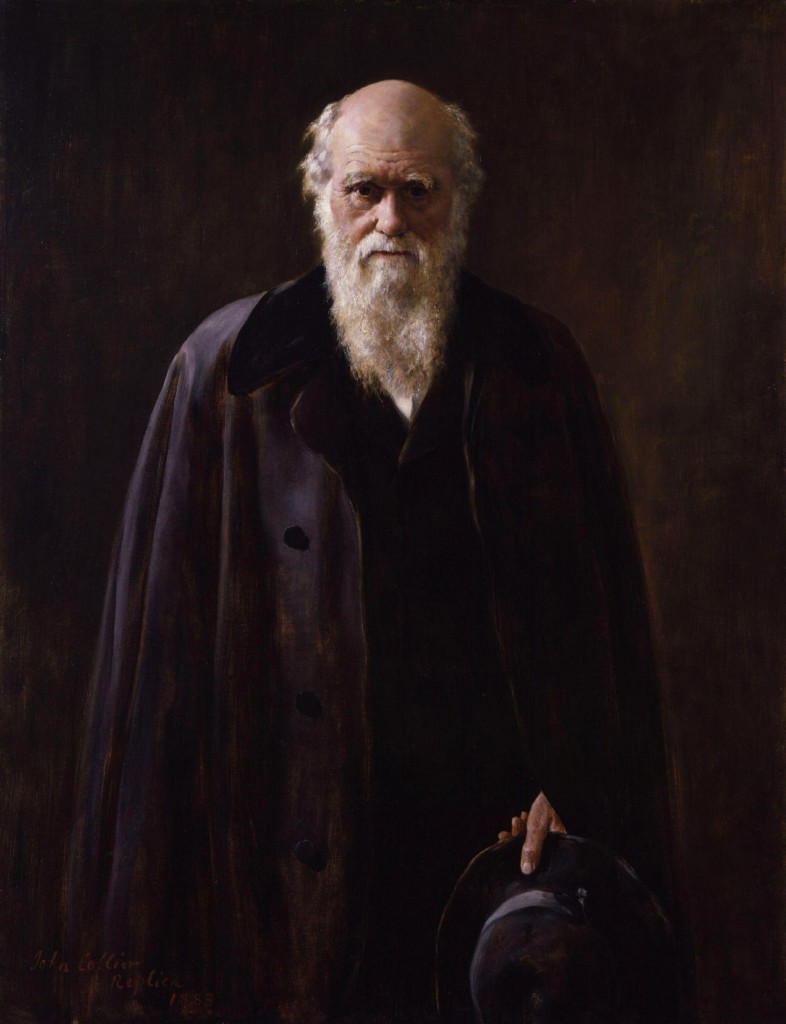

Oil painting of Charles Darwin by John Maler Collier, 1883, London, National Portrait Gallery. http://www.kingsacademy.com/mhodges/11_Western-Art/23_Later-19th-Century-Romanticism/23_Later-19th-Century-Romanticism.htm or http://bit.ly/Mar090