Why ‘they’ still don’t hate ‘us’

By Mark LeVine, 26 Sep 2012 08:07

I knew the title to my second book would be Why They Don’t Hate Us before the last embers of what had been the World Trade Center had cooled. Life in New York City was just beginning to reanimate after two weeks in which everything seemed frozen in time. The only thing that seemed to move was the ash and dust from the wreckage of the World Trade Center which daily covered New York City with a fresh coat of death.

Walking through the bowels of the Times Square subway station I passed a Hudson News stand and caught sight of the just published September 28, 2001, issue of Newsweek, with the title “Why They Hate Us: The Roots of Islamic Rage” emblazoned across it over an image of a young boy dressed in traditional garb holding a toy AK-47. The absurdity of the title – as if the world could so neatly be divided into a “we” and a “they” each, playing our respective roles in some preordained clash of civilisations – provided the perfect foil to summarise the main argument of my research on the impact of globalisation in the Middle East during the last two years.

The similarity between that cover and the much-debated cover of last week’s issue of Newsweek, with the title “Muslim Rage” boldly written over an image of screaming Muslim men, is striking. So is the fact that in each case Newsweek had a well-known nominally Muslim writer with little public connection to their faith – Ayaan Hirsi Ali in fact is a self-described atheist – explain what the “West” must do to win, or at least cope with the irrational masses about whom they claim authority to speak.

Whether in 2001 or 2012, the need to generalise about almost one-fourth of humanity, and the benefits of doing is, are evident from the opening sentences of the two articles.

Muslims or Arabs?

In the piercing aftermath of 9/11, Fareed Zakaria pointed out that “there are billions of poor and weak and oppressed people around the world. They don’t turn planes into bombs. They don’t blow themselves up to kill thousands of civilians… There is something stronger at work here than deprivation and jealousy. Something that can move men to kill but also to die”. He went on to argue that the rage that motivated the 9/11 terrorists came “out of a culture that reinforces their hostility, distrust and hatred of the West – and of America in particular”.

Zakaria did not blame Islam per se; his scorn was focused on its Arab heartland. He declared that while countries like Indonesia were dutifully following the West’s advice on economic and political reform the Arab world was a cesspool of anti-American fury and suicide bombings. His misreading of his Pakistan as a relatively moderate country compared with Egypt or Syria remains as shocking as it is telling.

“By the late 1980s,” he argued, “while the rest of the world was watching old regimes from Moscow to Prague to Seoul to Johannesburg crack, the Arabs were stuck with their ageing dictators and corrupt kings.” Apparently the fact that all of these regimes were, as he pointed out, brutal dictatorships with long histories of torturing their peoples, apparently had little to do with their alleged “choice”. Instead, it’s “disillusionment with the West” and a “lack of ideas” that is “at the heart of the problem”.

These views, according to the author, have “paralysed Arab civilisation”, and led a region “that had once yearned for modernity” to “reject it dramatically”.

Venality and carelessness, in spades

Zakaria admitted that the United States had been too cozy with the region’s ubiquitous strong-men. But “America has not been venal in the Arab world”, explained, “only careless”. His ignorance – willful or not; the reader can decide which is worse – of American policies and their motivations in the Middle East is as astonishing today as it was on September 12, 2001. But it was absolutely crucial that America at worst be “careless” rather than “venal”. If it turned out that decades of support for some of the most oppressive regimes in the world was the result of deliberate policies, what would that say about “us”?

Declaring himself part of the “we” against whom the Arab world is waging war, Zakaria stated that “we”, “cannot offer the Arab world support for its solution [to the Palestinian problem] – the extinction of the state… Similarly, we cannot abandon our policy of containing Saddam Hussein. He is building weapons of mass destruction”.

We might mention that the declared policy of the majority of Arab states in 2001 was to support the Oslo peace process while Saddam Hussein was not building WMDs. But the facts don’t really matter compared with the powerful perception Zakaria’s attitude helped to generate and sustain in the next decade. That “they” are fundamentally incompatible and unable to live among “us” is too self-evidently true to be challenged by mere facts.

Ayaan Hirsi Ali, the Somali-born Dutch political activist and former Parliamentarian, similarly defines herself as part of the “we” against whom irrational Islam is rearing its ugly head. “Once again the streets of the Arab world are burning with false outrage. But we must hold our heads up high,” she begins her article by declaring.

Like Zakaria a decade before, Ali sees little need to explain who “they” are. “Islam’s rage reared its ugly head again last week”, and thus it is Muslims as a collective who are responsible. Ali argues that the murder of the Ambassador and members of his entourage was the result of a “raging mob” who under the watch of a “negligent or complicit” government. That the murders were the result of a well-planned attack by a terrorist group in a region that the government has yet to be able to bring under its control (in good measure thanks to all the weaponry released by the US-sponsored insurgency against Gaddafi) is irrelevant.

Islam is nothing less or more than an anti-Western and anti-modern mob. Whether in Libya or in Egypt, it’s clear that Muslims are making a “free choice” to “reject freedom as the West understands it” in favour of governments that “stand for ideals diametrically opposed to those upheld by the United States”.

Never mind that the “values” of the United States includes supporting corrupt and brutal dictatorships and occupations, launching wars of aggression based on lies, violating its own constitutional principles to detain indefinitely, torture and even murder suspected enemies (including its own citizens). Or that a small but politically powerful percentage of American citizens seem as determined to incite violence in the Muslim world as their counterparts there seem determined to launch violence against Westerners. If Islam is defined by the rage of a small part of its adherents, the West is defined by the abstract liberal ideals that never have to be actualised in practice to remain the standard against which others – but not the West – are measured.

Disaggregating us and them

Neither Zakaria in 2001 nor Ali today can offer any real advice for how “we” can deal with “them”, for four reasons.

First, so many of their facts were and remain wrong that their larger arguments aren’t very useful. The problem is actually more damaging to Ali because, unlike Zakaria, she has a very powerful personal story of suffering at the hands of an oppressive, violent and patriarchal culture in her native Somalia that deserves to be heard. Sadly, it is undermined by broad generalisations and inaccurate claims she makes.

Second, both authors completely leave out the history and ongoing realities of Western/US support for violent and even murderous regimes across the region, which lies at the foundation of much of the quite understandable anger and rage of Muslims against the US or European governments. It is not the only reason for it, and it doesn’t excuse terrorism against civilians, whether Muslims or so-called “infidels”, or the widespread religiously grounded prejudices or oppression across the Arab/Muslim world. But the rage for which they are attempting to account simply cannot be understood, never mind addressed, without placing such policies at the centre for any analysis.

Similarly, both authors make scant mention of the quite long history and ongoing reality of “irrational” rage among “Western” Christians or Jews against Islam which, aside from its role in the present video scandal, has had at least as profound an impact on the policies of the American or Israeli governments towards Muslims as Islamic rage has had on the policies of most Arab/Muslim governments towards the US or Israel.

Third, both Zakaria and Ali, and their colleagues (both fellow Muslims like Fouad Ajami and Irshad Manji and the broader mainstream and conservative punditocracy), generalise from the most extreme segments of Arab/Muslim societies to Arab/Muslim “civilisation” as a whole. The simple fact is that the vast majority of Muslims have not been engaged in an irrational hatred of the West or unwillingness to engage with the basic tenets of modernity. As with their counterparts in Western countries and globally, they are just trying to survive and build a better life for their children.

No matter how reprehensible is the behaviour of violent protesters during the most recent protests, they comprise only the smallest percentage of the world’s Muslims, and their actions in fact have produced a wide backlash against them, from citizens attacking extremist headquarters in Benghazi to progressive Muslims writing detailed rebuttals to the ideologies underlying such actions. Moreover, no matter how unacceptable the ongoing oppression of women or minorities in the Muslim world is, such actions are neither unique to the Muslim world, nor are they the primary source of the rage these articles seek to explain.

Fourth, all the “rage” writers completely ignore the long history of interaction and support between people in the “West” and “Muslim” world – from interfaith jam sessions in medieval al-Andalus to kings and sultans, beys and deys, allying against common enemies on both sides of the religious divide in the unceasing great power games of the early modern era, to tens of thousands of European migrants building multi-ethnic, religious and linguistic communities in 19th century Alexandria or Tunis (in which former Christian slaves could rise to high government positions), to anarchist-inspired activist collectives conspiring together against authoritarian capitalist elites in early 20th – and now 21st – century Cairo, Madrid and Wall Street.

Of course, such collaborations also have had their much darker side, in the cozy relationships between Western and Arab/Muslim governments. Whether it’s freedom fighters morphing into terrorists (a la Osama bin Laden), or terrorists becoming freedom fighters (as we’ve seen occur just last week with the Obama administration’s decision to remove the MEK from the list of terrorist organisations), such policies are at the root of the broader distortions in the relationships between the Muslim majority world and the West that most “rage” writers fail to explain.

Maybe they do hate us?

If the Arab uprisings of the last two years have taught us anything, it is that there is no such thing as one Arab personality or culture. Just as the US is seemingly evenly divided between two broad trends that can scarcely be considered part of the same identity, most every Arab/Muslim country is riven by overlapping class, ethnic, sectarian, tribal, national and other conflicts.

The one generality that increasingly unites people across the globe, however, is the clear lack of solidarity between the wealthiest members of all societies and their poorer compatriots. Whether it’s the richest 1.5 per cent in the United States, 5 per cent in Pakistan or 10 per cent in Egypt or Morocco, contemporary neoliberal, globalised capitalism is uniting the interests of elites against the rest of their societies – and as a result, the interests of the rest of us together in opposition, like never before. This was clear to anyone lucky enough to be in Tunis or Cairo during their initial uprisings, or Milwaukee, Lower Manhattan and Madrid no[t] longer thereafter.

When you look at the incredible damage being wrought by energy, mining, agribusiness, food processing, weapons, and so many other industries on the planet, from global warming to rain forest destruction to the poisoning of large swaths of the land and sea, it’s hard not to believe that they – the political and economic elites who manage the world today and control most of its resources and wealth – really do hate the rest of us. Or at the very least, they couldn’t care less.

The German philosopher, Peter Sloterdijk, has argued that rage has long been a root force shaping societies. The problem is that it’s always been far too easy for those with power to misdirect the rage of others away from them and towards whatever social forces might challenge their control. But if rage all too often produces nihilistic anger and violence, it also can produce heroism and courage. The trick is to figure out how to channel and control the rage – not with anger, but with a positive vision of a future that address[es] and transcends the dynamics that lie beneath it.

This is precisely what the Arab uprisings, and soon after, the global Occupy movement, have begun to do. If the rage that increasingly swirls around all our societies can be channelled and directed against those who truly threaten our collective future, the sooner we might be able slow, if not stop, the inexorable march towards ecological disaster and a new feudal age.

Mark LeVine is professor of Middle Eastern history at UC Irvine and distinguished visiting professor at the Centre for Middle Eastern Studies at Lund University in Sweden and the author of the forthcoming book about the revolutions in the Arab world, The Five Year Old Who Toppled a Pharaoh. His book, Heavy Metal Islam, which focused on ‘rock and resistance and the struggle for soul’ in the evolving music scene of the Middle East and North Africa, was published in 2008.

http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2012/09/201292661444773258.html or http://aje.me/SQI2Jk

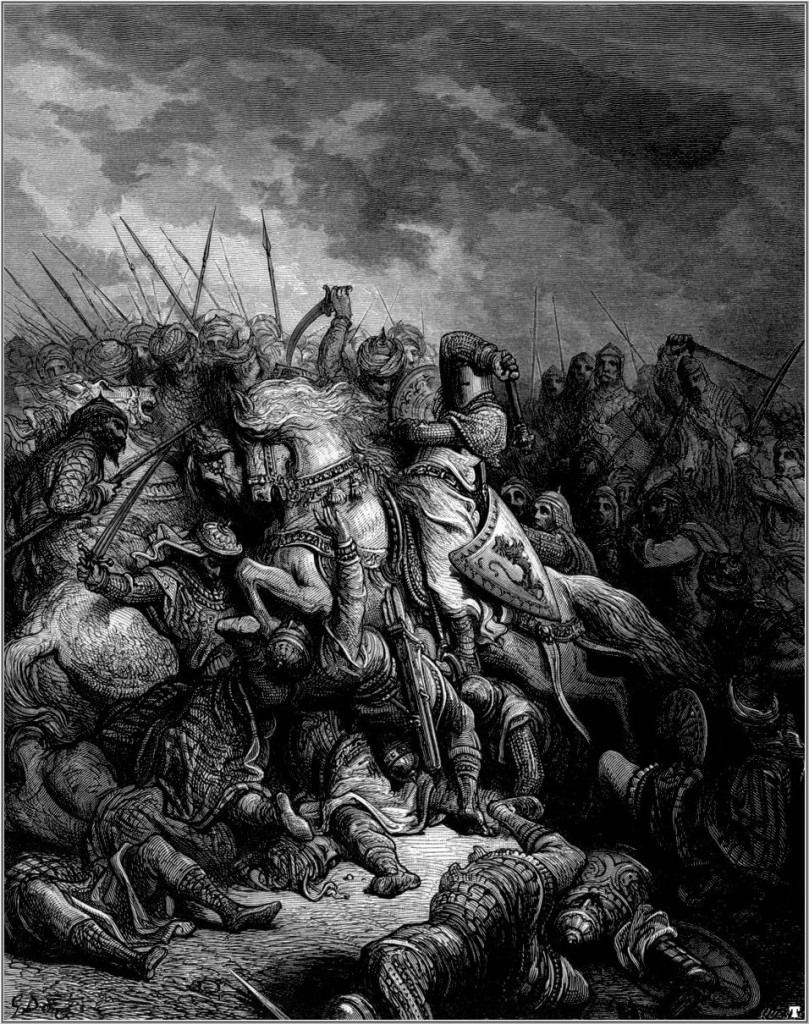

Engraving by Gustave Doré (1832-1883). http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Gustave_dore_crusades_richard_and_saladin_at_the_battle_of_arsuf.jpg or http://bit.ly/OZMGt8