The controversy around Zero Dark Thirty: As misleading as the film itself

The controversy around Zero Dark Thirty: As misleading as the film itself

By Ramzi Kassem, 19 Jan 2013 15:20

The controversy surrounding Zero Dark Thirty has been as misguided as the film itself, which opened nationwide on Friday. Much of the debate has centred on whether Hurt Locker director Kathryn Bigelow’s latest opus leaves viewers with the false impression that torture led to the killing of Osama bin Laden. That both the means employed and the ends achieved in that equation are illegal and repugnant seems all but forgotten. Both torture and extrajudicial executions are anathema to civilised society, irrespective of their possible efficacy or expediency. More importantly, both the film and the controversy it has ignited treat torture at secret CIA prisons as though it were a thing of the past, masking the reality of an enduring practice.

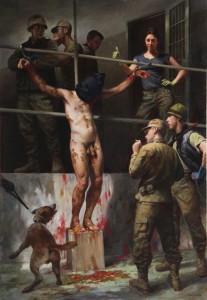

The first third of Zero Dark Thirty is unadulterated torture porn, a display of medieval cruelty at various CIA and affiliated prisons. Strappado, drowning, sexual abuse, beatings, stress positions, loud music, stuffing people into boxes, sleep deprivation, but also – and this is not acknowledged enough as torture – threats to send prisoners to countries where they would face further abuse (in the film, Israel). My clients at Guantánamo and Bagram survived such savagery at the hands of their American captors. I can attest that its traces on their bodies and minds are real and lasting. But the film cares not an ounce for those consequences, lingering instead on the torturers’ feelings about their crimes.

The film alludes to one of President Obama’s first acts in office: ordering the closure of CIA “detention facilities” and forbidding the agency from operating prisons again. An often-overlooked provision, however, exempts “short-term, transitory” facilities from the order. In a statement last month regarding CIA detention, Senator Dianne Feinstein lamented as “terrible mistakes” only “long-term, clandestine ‘black sites’.” The effect of these verbal gymnastics is to preserve the CIA’s ability to hold prisoners directly, albeit short-term.

And while Obama limited interrogation techniques to those listed in the Army Field Manual, that document was modified in 2006 to permit stress positions, sleep deprivation, and isolation – methods amounting to torture that are depicted in Zero Dark Thirty. The notion that the CIA no longer tortures prisoners, then, can only result from real or feigned ignorance.

Equally intact, of course, is the US government’s continuing reliance on proxy detention, where foreign regimes do the dirty work of imprisoning, interrogating, and often abusing prisoners without process, at the behest (and sometimes with the participation) of US agents.

To be sure, Zero Dark Thirty is misleading on its own terms. It begins with the claim that it is “based on firsthand accounts of actual events”. In what is perhaps the film’s only truly sophisticated, if unintended, insight, we see its heroine paradoxically overcoming subordination in a male-dominated profession while participating in the subjugation of Muslim prisoners, as she comes to fully embrace her sadistic role. Relying on a panoply of torture tricks reminiscent of your basic dictatorship (notwithstanding the obscene American conceit that ours is a more elevated, controlled form of torture), we watch as US agents extract information from a string of prisoners. It is this portrayal of torture bearing fruit that the Senate Intelligence Committee has condemned as “grossly inaccurate” based on its review of more than six million pages of classified intelligence records.

The final act of Zero Dark Thirty depicts the Abbottabad raid. Though it is the closest this film lover ever wants to come to a snuff movie, it does get one thing right: the raid was a “kill operation”, an ordered execution, despite the administration’s tepid protestations that US commandos were prepared to capture the unarmed bin Laden if only he had known to surrender in precisely the right way.

Zero Dark Thirty aspires to be a dispassionate exposition of the facts as they unfolded. But because their presentation is informed by and told from the perspective of the American operatives involved in the search for bin Laden, it is unsurprising that these filmmakers were “captured” by government officials with an agenda to justify their crimes. As such, the film cannot be neutral, no more than embedded war reporting can pass for truly independent journalism. In the end, Bigelow is an embedded filmmaker, and, from that position, her work cannot offer the critical, questioning perspective that defines art.

Unfortunately, the film’s errors and biases have focused national attention on whether torture “worked” and if the film got that “right”. That there has been no real accountability for past and ongoing crimes barely registers in the discussion. Far from highlighting that sad truth, Zero Dark Thirty lionizes those who ordered and implemented torture. In this respect, the filmmakers are complicit in reinforcing the impunity shielding the culprits.

Some would call that propaganda, and many of the film’s admirers as well as its critics have fallen for it.

Ramzi Kassem is a professor at the City University of New York School of Law. With his students, Professor Kassem represents prisoners of various nationalities presently or formerly held at American facilities at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, at Bagram Air Base, Afghanistan, at so-called “Black Sites”, and at other detention sites worldwide.

http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2013/01/20131191566253143.html or http://aje.me/10HgTmk

Painting “Torture Abu Ghraib,” 46” x 32” oil on canvas, 2009, by Max Ginsburg. http://snippits-and-slappits.blogspot.com/2012/06/todays-image-june-9-2012.html