The Bethlehem story takes us deeper into what it means to be human

By Giles Fraser, Friday 20 December 2013 14.30 EST

It is not the present that they expected. Nothing close. They wanted the sort of God who would drive out the Romans. They wanted the sort of God that would set them in positions of power and authority. They wanted the sort of God who would answer their questions and make them feel good about themselves. No, it was nothing vaguely close.

Freud attacks religion for presenting us with a permanent and all-powerful father figure who will look after us and provide us with boundaries, thus to replace the father we lost in childhood. It is a neurotic technique of anxiety reduction, helping us psychologically to manage an out-of-control world. But the God discovered by the Magi and the Shepherds could not be more different. Not just God as human, but – just to rub in the point about powerlessness – God as a human baby.

Such a God just cannot function as the focus of anxiety reduction. It is almost as if the creator of heaven and earth has resigned his job as warden of the universe and reincarnated as the very thing that some human beings had wanted God to help us escape from: the raw limits of human existence. From here on in, for Christians at least, God is not to be set against humanism, but seen as its fiercest advocate.

And as God himself furiously throws out his unco-ordinated limbs and screams in need of food and shelter, as all babies do, so it begins to dawn on the little Bethlehem gathering that the responsibility for human care could not be subcontracted to some power in the sky.

In an astonishing use of the Greek word kenosis – meaning emptying – the writer of the letter to the Philippians explains the incarnation in terms of God emptying himself, making himself nothing. Little wonder some theologians have felt the psychological impact of Christmas to be almost indistinguishable from the psychological impact of the death of God. As WH Auden asks, desperately: “Was the triumphant answer to be this?”

At the end of the Tempest, Prospero gives up all his magic powers thus to make his way in the world as a mere human being. I find it a profoundly Christian and kenotic moment because, as I understand it, Christianity is, among other things, a sort of slow training in weaning human beings off their powerful belief in magic. Magic, we might say, is the denial of necessity, the denial that there are things about human existence – like death – that we cannot change by waving a wand or reciting a spell. This has nothing to do with Harry Potter – magic is the refusal of human limit. Which is why I would want to argue that there can be just as much magic in science as there can be in religion.

Yes, of course religion can be especially susceptible to it. But the attempt to transcend the constituent limits of our humanity is just as evident in the absurd fantasy of cryogenic deathlessness or the peculiar imagination of post-humanism. Technology can be as much a shelter for the belief in magic as religion ever was. And often with far less self-critical vigilance – as if the vague presence of science constitutes a fail-safe prophylactic against fantasy. Indeed, the psychological fantasy of magic is at its most powerful when it works in places where it is least expected.

What happened in Bethlehem was something quite different. The Magi travelled from the east to seek out the extraordinary. What they found was a child. Something perfectly ordinary and perfectly extraordinary at the same time. A source of salvation not by magic but by taking us deeper into the very question of what it means to be human: love, kindness and generosity. And there they found God.

http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/belief/2013/dec/20/bethlehem-story-deeper-human-christmas or http://bit.ly/JMszwG

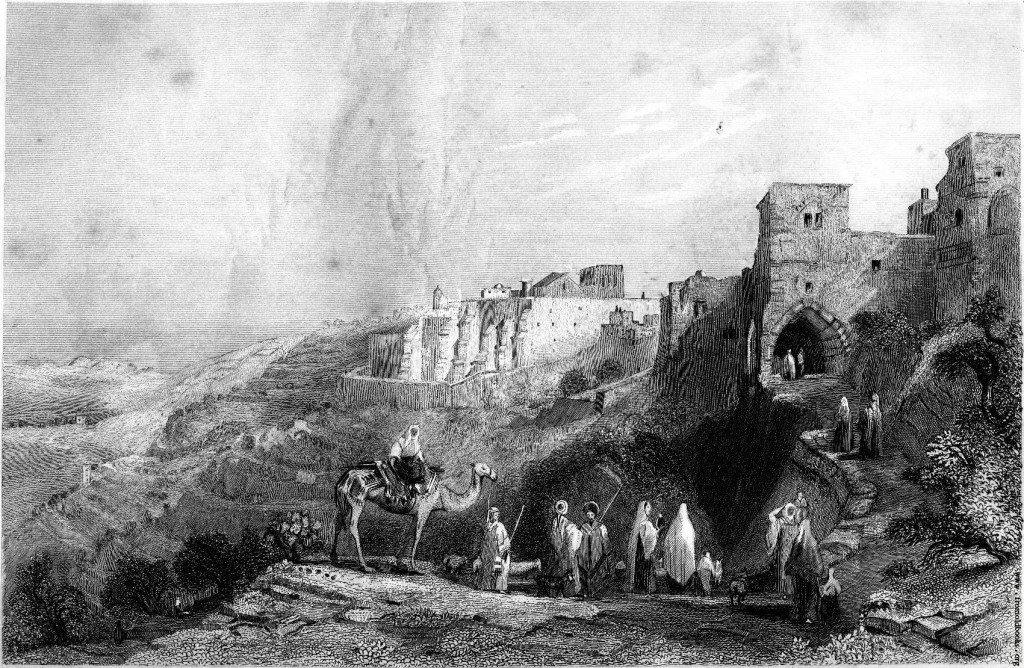

Illustration by Mead Clarke: “Christian Parlor Magazine Vol III” (1847). http://www.fromoldbooks.org/MeadClarke-ChristianParlorMagazine-Vol-III/pages/285-Bethlehem/ or http://bit.ly/1krrb0U