Important!

Once upon a time in Stillwater, Oklahoma, on a cold January night in 1975, I had the distinct pleasure of seeing and hearing a unique gathering of Delta bluesmen. Here’s the clipping from the top of page 4 of the 1/22/1975 edition of The Daily O’Collegian (Oklahoma State’s college paper)…

…and here are the fascinating stories of the Memphis Blues Caravan, as told by Arne Brogger. Mr. Brogger wrote me today and added “It was an extraordinary experience, from start to finish (and the finish ended at a lot of gravesides). Real damn American History.”

The Short Version

The Short Version

The birth of the Memphis Blues Caravan occurred late one night in Steve LaVere’s music store in Memphis. LaVere and I had become acquainted through some dates I had booked for Furry Lewis. I had arranged these dates after finding LaVere’s number in the Billboard performance publication as the contact for personal appearances for Furry. Steve and I had hit it off as fellow “old souls” supported by our mutual love of the blues.

What Do You Think He Looks Like…?

In June of 1973, I was in Memphis and we were sitting in his shop at about 1:00 a.m., listening to some old 78’s in his collection. In the course of the conversation, Steve asked me if I had ever seen a picture of Robert Johnson. I, of course, told him “no,” as a picture of the legend of the blues did not exist. He asked me what I pictured Johnson looking like in my mind’s eye. I described what I thought he might look like. LaVere then reached for a manila envelope, about 6″ by 5″ inches in size. He pulled out a black and white photo of a very dapper black man in a suit and tie, wearing a snappy looking hat and holding a guitar. “That’s Robert Johnson,” he said.

I was dumbstruck. There he was, lost for all these years, looking exactly as I had pictured him. “Are your sure this is him?” I asked. “Without a doubt,” Steve told me. “I found his sister in Washington DC. She gave this to me.”

We both sat in silence for a long time. Blind Lemon Jefferson scratched on the old 78. We stared at the picture. “People have to see this, Steve,” I finally said. He said he had plans to copyright the image in conjunction with Robert’s sister. As soon as that was done, he would release it. “Who else has seen this,” I asked. “You, me and a couple of folks here in Memphis. I just got it last week.”

To Be Seen — And Heard…

The discussion then turned to the need for people to see the guys who invented this uniquely American art form. Steve had made contact with virtually every blues musician of consequence in Memphis, the “home of the blues in the known universe.” It was decided that we would try to put the whole crew who lived in Memphis on the road. It had never been done before. Personal appearances by local blues musicians had been, for the most part, solo date affairs. While most of the musicians knew each other, they had never toured or performed together as a group.

Kill The Fatted Calf…

We began our exploration of potential members with a visit to the home of Revered Robert Wilkins. Wilkins had recorded some powerful sides in the late 20’s and early 30’s for “race labels” and had enjoyed great success. Unfortunately for the blues world, Wilkins “heard the call” and became an ordained minister in the mid-30’s. He vowed never to play the blues again. It was a vow that he would not break.

Sitting in Rev. Wilkins’ living room in Memphis, Steve and I described to him what we were interested in doing. Rev. Wilkins explained to us his vow to give up the “Devil’s music,” though we sensed that his resolve might not be totally unshakeable. The blues he performed on those early recordings were done primarily in the key of A. All of his religious material was done largely in the key of E. He sat with this guitar on his lap and, after much coaching by Steve, he tuned up to A. We sat on the edge of our seats. As he struck the strings after finally tuning up, and that A chord rang though his house, his wife, who was in the kitchen, suddenly appeared. “Robert, you best not be doin’ what I think you’re doin’.” The guitar was quickly tuned down to E and the air went out of our balloon.

Rev. Wilkins told us that he would be unable to join us in this adventure, but wished us well. He then proceeded to play a few tunes he had written. One of these was a song which, he announced proudly, had just been done by “some English boys,” a group called The Rolling Stones. He then launched into “Prodigal Son,” one of the many choice cuts off the “Beggars Banquet” LP. The tune closed with the chorus verse, “that’s the way for us to get along….” And indeed it was. He was still contributing through his music, but on his own terms. He seemed a genuinely happy man.

Hit The Road…

Other visits to various artists followed over the next few days (enumerated in the pieces on Furry, Bukka, Red, et. al). By the end of the week, we had commitments from virtually all of the musicians who would later comprise the last, and only, great touring ensemble of classic country blues, The Memphis Blues Caravan.

It was now my job to get on the phone and start spreading the gospel and exciting commercial interest in the entourage. The first and most logical place to start, I thought, was in contacting college campuses around the country. The reaction was almost uniformly positive and, God bless them, the offers started rolling in.

Once the initial tour dates were booked, the job of logistics became daunting. We had to move twelve performers, a road manager and various pieces of equipment from Memphis to each date. In addition to salaries, we had the expense of transportation, per diems, lodging, “incidentals” (i.e. beverages) and the like to deal with. Hotel rooms had to be booked, stage and lighting plots had to be arranged, set orders and lengths had to a determined, egos had to be considered. The job became more complex by the day. And all of this had to be done before we ever played our first date.

Tour logistics fell to me, with Steve concentrating on set order, billing and “artist relations.” Flying to the dates was out of the question, as our budget was tight at best. We were not dealing with “pop star” money, but we had the same problems and requirements as a major rock tour. I decided that the best way to move the group was by chartered bus, and I struck a deal with Greyhound to provide equipment and drivers. Our first few tours were done in leased commercial coaches. This proved to be both unwieldy and expensive. It also did not provide the “comfort factor” needed for a prolonged stint on the road. By the third tour, we had wised up and found a company in Nashville that specialized in tour bus leasing and provided equipment with lounges, bunks, a galley and a head. The real deal. They also provided a driver who would be with us for the duration of the tour and who became, usually by the second night of the tour, a “member of the family.” In the space at the front of the bus, facing oncoming traffic, was a sign that usually read “Chartered.” We made a sign which simply said “Heaven,” put it on the front of the bus and hit the road.

Welcome To Chicago…

Our first date was at Northwestern University in the Chicago suburb of Evanston, Illinois. When Furry Lewis and I first met, I introduced him to a friend of mine, David Calvit, who quickly became one of Furry’s biggest fans. David owned a large travel agency in Minneapolis named Corporate Travel. His company specialized in just that, corporate travel. Blues performers were about as far from his usual clientele as you could get.

As I attempted to secure reasonable lodging in the Chicago area, I ran into problems. Eight rooms at bargain rates were not to be found. I called David and explained the situation. He listened quietly. “Furry is going to on these dates, right?” he asked. “Of course,” I told him. He said he would call me back.

The next day he called and told me we had nine rooms at the Lake Shore Holiday Inn on Lake Shore Drive in Chicago. I knew from travels to Chicago that this was one of Holiday Inn’s premier properties in the Midwest. “That’s great, David, but we can’t afford the wood,” I told him, as I knew that the rack rate for rooms at that property were in the low $100’s. In 1973, this was a lot of money. “Your rate,” he said, “is $35.00 per night.” I told him it was great to know a man who could pull the right strings. Little did I know.

When we arrived at the hotel from Memphis, the night before the show, the marquee facing Lake Shore Drive was ablaze with the words “Welcome, Memphis Blues Caravan.” We checked in to find real “rock star” service. A complimentary fruit basket (with a handwritten note to each artist) was in each room. Furry Lewis had his own room. The penthouse suite at the top of the hotel with panoramic views of Lake Michigan and the Chicago skyline. Life was good.

I will never forget the looks on the faces of these musicians at what they beheld. As I got Joe Willie Wilkins settled in his room, his bass player, Melvin Lee, turned to me and asked in a whisper, “Is all this for us?” “Yeah,” I said, as casually as I could. “You’re a member of the Memphis Blues Caravan, aren’t you?”

So we began … spreading the gospel, knocking audiences on their collective asses, and having a hell of a time.

http://thebluehighway.com/blues/mbc.html

The Straight Oil From The Can: Tales from the Memphis Blues Caravan and other stories…

The Straight Oil From The Can: Tales from the Memphis Blues Caravan and other stories…

By Arne Brogger, http://thesilvereagle.blogspot.com

November – 1975

The Memphis Blues Caravan was about to take the stage.

Seated in the brightly lit dressing room, encircled with vanity mirrors ringed with soft 40 watt bulbs, Bukka White opened the battered case holding his National Steel Guitar and quickly tuned to Spanish. Across the room Furry Lewis leaned back in his chair and announced to whomever would listen that he was READY. Joe Willie Wilkins rolled his eyes. His band perused the cold cuts on the hospitality table – inquiring where the fried chicken had gone. Someone accused Hammy Nixon of getting to it first and Sleepy John Estes allowed as that might well be what happened to the chicken. Hammy, smiling, said nothing. Piano Red, wearing his trademark dark glasses and narrow brimmed hat, sat perched on a chair, his enormous frame extending considerably from either side. Smiling and nodding at the fraternal hilarity, his fingers moved unconsciously as his hands rested on massive legs, perhaps rehearsing the opening tune of his set.

Suddenly, the stage manager’s voice came over the intercom. “Five minutes, gentlemen…” Red stood immediately, the smile gone and pre-show tension showing on his usually impassive face. “Guess I better go out there and do it.” All conversation stopped as Red received the full attention of everyone in the room. “Go get ’em, cud’n” Furry said as Red walked past him and disappeared out the door.

I walked Red to the stage and watched as he took his place at the piano. The curtain was closed and the area illuminated only by blue ‘work lights’. The stage manager, standing next to me and wearing a headset and mic, quietly said the words which would start the process that tonight’s audience had paid to witness, “House to half…” The house lights were cheated down to half strength. Once seated, Red adjusted his vocal mic, positioned himself on his seat and then turned to me and nodded. We had done this many times before and there was an unspoken agreement that nothing would happen until I received that nod. Turning to the stage manager, I in turn nodded. Holding the mouthpiece of his headset in his right hand, he whispered, “house to black…and…curtain.”

Memphis Piano Red’s left hand rolled like thunder as the curtain rose and the lights came up on stage. A spontaneous roar from the audience announced that the show had begun.

This is a story about the men and women who comprised The Memphis Blues Caravan, the last and only touring ensemble of American country Blues artists, the guys who originated the art-form we know as the Blues. My name is Arne Brogger. I was the guy who walked Red to that stage. But that’s not important – what’s important is the story I’m about to tell you.

Posted Thursday, September 3, 2009

Memphis…

Standing there watching Red I almost wondered aloud at my good fortune. I was hangin’ with the guys…guys from Memphis. Blues players. The best in the business – practitioners of the art form they helped to invent. A race of dinosaurs, rare and unique – and about to disappear forever.

Their hometown, Memphis, TN, was chartered as a city in 1819 and is the only major US city whose name traces its origins to the African continent. Five thousand years earlier Memes, a little known warrior king, united the northern and southern kingdoms of Egypt and established a city to serve as its capital. The city was called Memphis. Situated south of the Nile delta, it occupied, in its proximity to a mighty river, the same locale (in mirror opposite), as the city which would eventually share its name. Ancient Memphis would be home to the great treasures left the world by Egyptian civilization – the Great Pyramids, The Sphynix and the Necropolis. Much of what we know of Egyptian antiquity comes from archaeological findings unearthed in and around ancient Memphis. It was an area rich in talented artisans whose craft and art accompanied the royal and wealthy on their journeys into the next world.

The local Egyptian deity in the Memphis pantheon was the god Ptah. As the patron of artists and craftsmen, Ptah was also a creator deity. According to local belief he created mankind in his heart, using his voice as the prime moving life-force. That synergy of heart and voice in old Memphis would be recreated in its present-day namesake. And it would be known as the Blues. Like the stone edifices and finely crafted art of the ancients it would become a great treasure – not one lodged in a glass case or left to fade under the elements. It would live and breath, beckon and cajole, challenge and comfort. It would be music and it would change the world.

Posted Sunday, September 6, 2009

“I am a Japanese. The blues was much very good, but this person listens for the first time. I am very splendid! I was impressed! Thank you!”

The Blues is the voice of the heart – we respond to it, regardless of background or nationality. It is unafraid to speak what is felt and does so without shame or artifice. It is as self-conscious as a newborn. Its scope is inclusive, it does not separate people emotionally. Blues is human music – at once approachable and warm, welcoming and understanding. It opens its arms and lakes the listener in. Speaking to that common core shared by all mankind – our joy, our pain, our longings and out desires, the Blues has become great and important because it dwells on the primal. The power if this fact was grasped completely by the American artists who later helped invent jazz,country and, eventually, rock ‘n roll. The leap from the early Blues verse, echoing out of Mississippi, “Baby, please don’t go…” to Motown’s unashamed statement, “Ain’t too proud to beg, sweet darlin'” is as short as it is simple.

Famed anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss, speaking of the power of myth and its diminished role in modern society, suggested that music had taken on myth’s function. Music, he argued, had the ability to suggest, with primal narrative power, the conflicting forces and ideas that lie at the foundation of society. And that is society as a whole of which he speaks – black and white. Our shared humanity.

Blues, as an art form, was created and perfected by southern Blacks. There is nothing particularly Black in its subject matter, in the general sense. But it is all about being Black in the specific sense. The Blues and being Black are inextricably linked.

The holds of slave ships carried humanity, not luggage. No pots, no pans, no family pictures, no cedar chests filled with homespun. The space for heirlooms was confined to the four or so inches between the ears of the cargo. From the physical meagerness of this beginning, came a rich treasure. Free of the intellectual constraints of European tradition and reduced to a social and economic status where they had nothing left to lose, those new arrivals eventually turned inward, unpacking what they had brought with them – their basic humanity. They set it to rhyme and meter and nestled it into twelve musical bars. In so doing, they created something that forever raised them far above the meagerness of that origin and, at the same time, gave an undeserved gift to their captors and their descendants. They made us all very splendid, indeed.

Posted Sunday, September 6, 2009

“Goin’ upstairs, gonna pack up all my clothes, Anybody ask about me, tell ’em I stepped outdoors…”

My introduction to the Blues came as a 9-year-old boy listening to old Stinson78’s from a collection titled “Negro Sinful Songs as Sung by Huddie ‘Leadbelly’ Ledbetter.” They belonged to the father of my 4th grade classmate, Steve Thomes, and we almost wore them out listening time and again. Waiting until his parents were safely out of the house, we would sneak into the den and pull out the album and listen for hours. “Fannin Street” was a fave, with its salacious lyric being of special appeal to a 9 year-old’s ears…you know the one, about the woman who “…lives on the backside of the jail….”

In retrospect, the influence exerted by this particular record collection was far-reaching. Often, we were bothered in our listening by a young man who lived in the downstairs portion of the duplex occupied by Steve and his family. He was a year younger and a grade behind us in school. As such, he was considered a “little kid” and his presence was tolerated but not encouraged. The “little kid’s” name was Mark Naftalin. Mark would later go on to join a band and make some records. The band he joined, as keyboardist, was the Paul Butterfield Blues Band appearing on their first release (Born In Chicago) as well as the seminal East West, the album which truly launched the Butterfield Blues Band.

Mark has remained in the music business and currently owns Winner Records (www.winnerrecords.com). Steve, while never going into the business professionally, picked up guitar in his early teens and, listening to those early 78’s, became one of the finest 12 string guitar players I’ve ever heard. Later, a high school classmate of ours, Dave ‘Snaker’ Ray, would go on to fame (but limited fortune) as one third of the influential early ’60s Electra Records Blues trio, Koerner Ray & Glover. His early exposure to the Blues began with a close listening to Steve’s Stinson collection. Interestingly enough, another University High School classmate of ours, Barry Hansen (a/k/a Dr. Demento of radio fame) also was influenced by this collection. Was it the collection – or something in the water at U-High…?

As a youngster and as a young man, my friends and I listened with fascination to recordings by newly re-discovered Blues artists. I often wondered what these guys were like, these guys whose music meant so much to me. I would later discover the answer to that question when I was given a front row seat to the grandest of performances – The Memphis Blues Caravan.

Posted Thursday, September 10, 2009

Gathering the Samurai – Furry Lewis

Furry Lewis stepped off a plane from Memphis on May 3, 1972. Until that moment, I had never laid eyes on an authentic ‘country Bluesman.’ I collected his bag, together with a beat-up guitar case (black, with a white, hand-painted crescent moon and stars on one side and the legend, ‘Furry Lewis – Memphis, Tenn’ on the other) and we drove back to my house in SW Minneapolis. Later that day we sat in my living room and he asked if I would like to hear a tune. As the house filled with the ringing of that open E-tuned guitar and the slap of his slide on its neck, I thought I’d died and gone to heaven. The first tune was free – and I was hooked.

I was working as an agent and a few weeks earlier, by lucky chance, I saw his name listed in a Billboard publication under the Personal Appearance section. The listing showed a number in Memphis. I called and Steve Lavere answered. After a brief discussion I discovered that Furry was not just “open” to play dates, he was “wide open.”

Furry lived alone in a house at 811 Mosby St. He had retired from his job as a street sweeper for the Memphis Department of Sanitation and wanted to work. I got on the phone and started telling the “Furry Lewis” story to anyone who would listen. Within three or four days I had a six day tour booked for early May. The dates played and were a resounding success.

After each show (all were within an easy drive from Minneapolis) we would return to the house where Furry would play for an hour or so, charming every one in the room. When our initial visit (a week or so) was over, Furry cried, I cried, my wife Dianne cried. I assured him that we had not seen the last of each other and a month or so later I was in Memphis and began the process of meeting his contemporaries. These encounters, facilitated by Steve, eventually resulted in the formation of The Memphis Blues Caravan, a touring entourage which included, at various times and in various combinations the likes of Bukka White, Sleepy John Estes & Hammy Nixon, Memphis Piano Red, Sam Chatmon, Memphis Ma Rainey, Big Sam Clark, Mose Vinson, Madame Van Hunt and perhaps some others – but definitely NOT the Rev. Robert Wilkins. Not for lack of effort on our part. Steve called him and asked if we could come by his house to discuss a proposition of mutual interest. He said he’d listen and on my second night in Memphis, we knocked on his door.

Posted Monday, September 14, 2009

Gathering the Samurai – Rev. Robert Wilkins

We stood at Reverend Robert Wilkins’ door. This was the first visit to potential members of what would become The Memphis Blues Caravan. Wilkins had recorded some powerful sides in the late 20’s and early 30’s for “race labels” and had enjoyed great success. Unfortunately for the Blues world, he “head the call” and became ordained as a Minister in the mid thirties. He vowed never to play the Blues again.

Ringing the bell, his wife answered and escorted us into the living room. I remember a red shag carpet, wall to wall, with spotless white painted woodwork. The furniture was comfortable and well kept and on the mantle piece were pictures of family and friends. Light green shades covered lamps at either end of the couch where Reverend Wilkins sat as we entered. The entire room seemed bathed in a serene yellow glow. Mrs. Wilkins excused herself and disappeared into the kitchen at the back of the house. Reverend Wilkins asked us to have a seat.

We described to him what we were interested in doing. He explained to us his vow to give up the “Devil’s music” though we sensed that his resolve might not be totally unshakable. The Blues he performed on those early recordings were done (I was told) primarily in the Key of A. All of his religious material was done largely in the Key of E. He sat with his guitar on his lap and, after much coaching from Steve, he tuned up to A. As he struck the strings after finally tuning up, and that A chord rang through the house, his wife suddenly appeared. “Robert, you best not be doin‘ what I think you’re doin‘!” The guitar was quickly tuned down to E and the air went out of our balloon.

Reverend Wilkins told us that he would be unable to join us in this adventure but wished us well. He then proceeded to play a few tunes he had written. One of these was a song which, he announced proudly, had been done by “some English boys” – a group called The Rolling Stones. He then launched into “Prodigal Son”. The tune closed with the line, “…and that’s the way for us to get along.” I had to agree. But there would be no Blues from Reverend Wilkins.

The next afternoon, I’d knock on the door of 1112 Walker Ave. and meet John Williams, a/k/a Memphis Piano Red.

[Below is Rev. Wilkins’ son, John, doing his father’s classic, “Prodigal Son.”]

Posted Wednesday, September 16, 2009

Gathering the Samurai – Memphis Piano Red

Red’s house on Walker had a covered porch where he spent most of his time when the weather was warm. He was sitting there when I arrived and I was quickly invited inside. To the left as you entered sat an upright piano and across the room was a couch and various chairs, arranged ‘audience’ style, facing the piano.

Red was a large man, heavy set and powerful. He had spent years as a furniture mover and looked, even in his late 70’s, as if he could toss a baby grand around. In his youth he had played various joints and whorehouses, hoboed around the south, playing where ever he could. Like most black folks named ‘Red’, he was an albino. He had a high pitched voice and sounded like a gentle, sweet person when he talked. Provoked, however, that sweetness could quickly disappear. I only saw that happen once, but it scared hell out of me.

We were on the road shooting part of a film for the BBC and had stopped for an alfresco lunch arranged by the producers. The film crew wandered from musician to musician during the picnic, filming and interviewing the various Caravan members. Red was seated on the ground, eating some fried chicken. Behind him, the ground sloped up a few degrees. As he sat busying himself with his food, a bottle of soda, sitting up-hill from Red, was overturned. The liquid ran down the incline, collecting around Red’s large frame. Red felt the dampness spread underneath him and spun around on all fours. Joe Willie and Bukka, seeing what happened, began to laugh. His neck bulging and his face a mask of furry, Red struggled to his feet. The laughter abruptly stopped. Both men, looking truly frightened, began to back up as Red rose. They quickly began an earnest attempt to calm him with denials of responsibility and suggestions that what happened was an accident. Red, looking like a large bull with evisceration on his mind, eventually calmed down. Who knows what might have happened had they not been successful in their pleas.

But on that warm June day in 1972 Memphis, Red was nothing but friendly and outgoing. He allowed as he liked the idea of playing on the road and was ready to leave that very day. Ever the obliging host, he offered up some home brewed beer and then sat down at the piano. After two or three glasses of the stuff you were lucky to be able to stand. The room filled with neighbors, kids and old folks, ready for whatever might happen. Red’s left hand rolled and pretty soon someone started the barbecue. Red played on almost every date the Caravan performed and was a pleasure to be around. Always good natured and friendly and – after the picnic incident – always treated with respect.

Posted Thursday, September 17, 2009

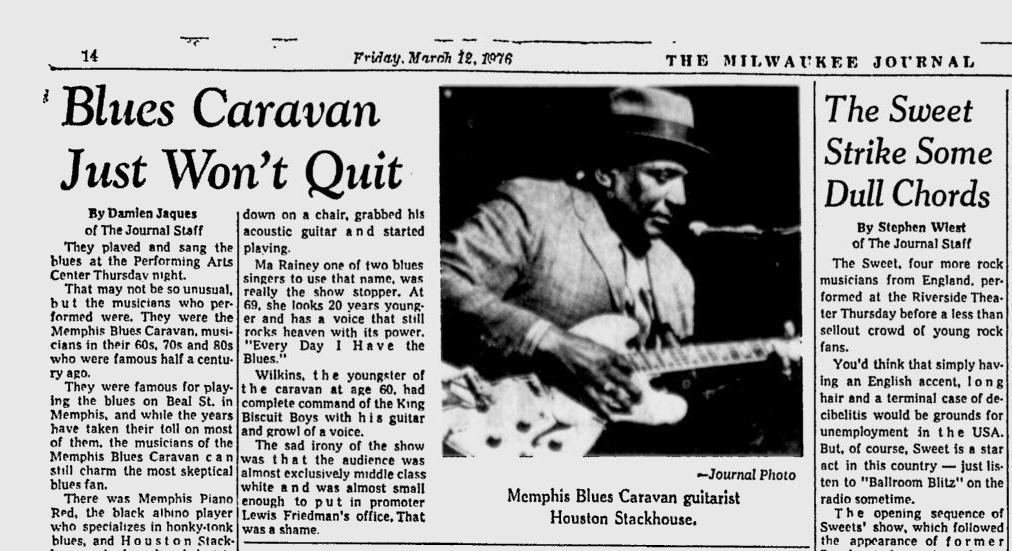

Gathering the Samurai – Joe Willie Wikins & Houston Stackhouse

Joe Willie and Stack were lifelong friends and had deservedly substantial reputations gained as the guitar players and vocalists in (Rice Miller) Sonny Boy Williamson’s King Biscuit Band. As such, they were featured performers on the seminal King Biscuit Flour radio program broadcast on station KFFA from Helena, AR in the forties. The first electric guitar Muddy Waters ever heard was played by Joe Willie and/or Stack.

When I met them they were living in a house on Carpenter Street along with Joe Willie’s wife, Carrie. The house was small and cluttered, but tidy. A record player stood next to the front wall and as I entered, “Smokestack Lightning” was coming from the small speaker in the front of the machine. “Howlin’ Woof”, as Carrie Wilkins pronounced it, provided background music that afternoon. Aside from the sparse furnishing, boxes of unknown contents and the old record player, on one wall hung the three pictures I had come to expect seeing in any home I visited in Black Memphis – FDR, JFK and MLK.

The day I arrived, Stack was in the backyard tending to a barbecue. He was cooking catfish. He had made a batter (the recipe for which he would not divulge, even to Carrie), dipping each fillet before placing it on the grill. Once the batter was browned, the fish was basted with a sauce (equally secret) and cooked a bit longer. I have eaten catfish at Gallitoirs in New Orleans, at the First-And-Last-Chance Cafe in Donaldsonville, LA and at Positanno in New York City. Nothing comes close to the magic wrought by Houston Stackhouse.

I had seen a picture of Joe Willie and Stack, taken in the 40’s at KFFA. The picture, a famous shot in Blues circles, shows Sonny Boy Williamson blowing harp, down center sits the drummer (the late Sam Carr) with “King Biscuit Boys” hand painted on the kick drum head and a very young Joe Willie Wilkins and Houston Stackhouse, standing center right, holding their guitars. As one can see from the picture, the young Joe Willie was a strikingly handsome man.

Years later, on the road with Joe Willie and the Caravan, the subject of the picture came up. Teasing Joe Willie, I remarked that he used to be a good looking guy – and asked him what happened. Joe smiled. Carrie, sitting across the room, shouted, “Good looking!? Shit, let me tell ya – I had’a pull women two-at-a-time off that motherfucker!”

Joe Willie continued to smile.

[Below is a video of Joe Willie Wilkins and Houston Stackhouse, with Stack doing the vocals.]

Posted Saturday, September 19, 2009

Cookin’…Furry’s greens…

We’ll get back to the ‘Samurai search’ but first, a few thoughts on food.

From Stackhouse’s catfish to Red’s barbecue, the members of the Caravan were, in their own way, gastronomes. Way before The Food Channel, Top Chief and all the other nitwit foodie propaganda, Southern cooking had long reined as a unique American cuisine. On the road, as often as not, conversation would turn to food and reminiscences of great meals. Tasty barbecue, catfish, chicken, and arcane treats like opossum, squirrel and rabbit. Each member it seemed, had a double, secret life as a chef/cook and would regale his fellows with tidbits and secrets which, when applied to a particular dish, would result in absolute perfection. Stack’s catfish sauce not withstanding, Furry Lewis was also accomplished in the kitchen and on one early fall day shared two of his specialties, greens and corn bread, with me and some friends.

In 1977, during one of his many stays at my house, Furry offered to cook. The offer was prompted by a discussion of Southern recipes he had with my friend (and his) David Calvit. David was from Alexandria, LA and brought to his marriage to a Minnesota native an array of old family recipes. His wife, Gretchen, in turn brought her own considerable culinary skills to bear on the information with the result that a small, select group of us Yankees were able to sample authentic Louisiana Creole and Cajun dishes (pre-Paul Prudhomm and all that “blackened” crap) and other Southern specialities as few could at that time and place.

The discussion David and Furry shared centered around greens and their proper preparation. It was more than a discussion. I recall some disagreement between the parties concerning some rather (to my ears) arcane and subtle variations in preparation. The exchange culminated in Furry volunteering to “show us” what properly prepared greens should look and taste like. David and I were dispatched to find ingredients.

Finding greens in Minneapolis was no easy chore for a couple of white guys. Our search eventually led us to a south side Red Owl supermarket. Entering, we were greeted with an array of goods not found at Lund’s, the Minneapolis middle-class food emporium we were used to. After making our way to the vegetable counter, David sorted through Collard greens and, after close examination, selected three bundles. Next, we moved to meat section and found a piece of fat-back (salt pork), as instructed. We made our purchases and returned to my house.

Furry examined the goods. The fat-back was judged too small. The greens were another story. “This is the best they had?” – the irritation showing in his voice. An artist about to create a masterpiece as important as proper greens did not want to be hampered (or sabotaged) by inferior ingredients. “That’s the best they had…” David said, a bit defensively. Furry was far from pleased. “Where’d you get these?” he asked. David and I looked at each other. “A store – about three miles from here.” Furry eyed us both. “Where’s my hat?”

The three of us drove to the Red Owl.

We entered the store, led by Furry wearing his tan fedora and dark pinstripe suit. He had a cane in his right hand and walked with a slow, measured step. Conversation at the cash register stopped as we made our way past it, heading for the vegetables. Surveying the greens, Furry shook his head. Suddenly, a voice behind us said, “May I help you, sir?” Turning, we regarded Vernon Biggs, Store Manager (as his name tag stated). Vernon was about the size of a black Buick with a voice that commanded awed attention. He spoke directly to Furry, well aware of who in the trio was in charge. What followed was an experience I never forgot.

Posted Monday, September 21, 2009

More about Furry’s greens – I’m with the band…

Mr. Biggs towered over the trio in front of the stack of greens at the south side Red Owl supermarket. “Can I help you with anything?” Furry Lewis, my friend David Calvit, and I all turned to behold the enormous store manager.

“Yeah – you got any decent greens?” said Furry, bluntly. In replying, Mr. Biggs (I’m sure) thought, for one fleeting moment, that he was addressing his grandfather or perhaps an aged uncle. “Certainly, sir. Let me see what we have in the back.” Moments later a large, flat cart appeared, pushed by Mr. Biggs. Piled on top were fresh, crisp greens, perhaps a bushel. Furry smiled. David and I smiled. Mr. Biggs smiled.

Examining the pile with a practiced eye, Furry made his selection and handed Mr. Biggs the three bunches of greens he had chosen. Biggs asked if there was anything else we needed. “Fatback” said Furry, “about yea…” holding up his hands to indicate size. “Of course” said Biggs. He placed the greens in a shopping cart and disappeared. We were about to make our way over to the meat counter when Biggs re-appeared. He held up two pieces of fatback, each freshly wrapped in plastic. “Like this?” he asked. Furry nodded, choosing the large of the two. Again, everybody smiled, especially the white guys and Mr. Biggs. “Corn bread” said Furry. David and I looked at each other. “Over here” said Biggs, taking Furry’s arm. We followed the mountain that was Biggs and Furry in his tan fedora to the dry mix shelf. Biggs made a suggestion, “Try this…” he said to Furry, it being obvious who was involved in the decision process.

Mr. Biggs escorted us to the cashier, pushing the shopping cart carrying the greens, fatback and corn meal with one hand, the other on Furry’s elbow . There was a line five deep at the only checkout lane open. Biggs walked to an empty lane, placed the items on the counter and called over his shoulder. “Jenny, can you come here a minute please?” A woman sitting in an open, elevated “office” in the corner of the store stopped what she was doing and quickly descended to the checkout area. “Can you help his gentleman?” he said, nodding to Furry.

“Of course, Mr. Biggs….”

Furry looked at Biggs, “What’s you’re name, boy?” I think I physically jumped at those words, as if I heard a gun shot. The idea of calling anyone of color “boy” was so foreign to my Northern ears, especially someone who looked like Mr. Biggs, that it physically startled me. David didn’t blink. I quickly realized that, at age 80-something (so he claimed…), EVERYBODY was a boy to Furry, and – he was a black guy from Memphis. Not an uptight Yankee who had lived his whole white life eating white food, going to white church, white school and hanging out with his white friends. If Furry were to have spoken in 21st Century vernacular he would have said, “chill, asshole…” to my reaction.

With his cataracts and coke-bottle glasses, Furry couldn’t see the name tag. “I’m Vernon,” said Biggs, extending his hand. “Pleased to meet you,” Furry allowed. “My pleasure” said Mr. Biggs, “y’all come back any time…”

In the music business there is a line that, when spoken with some authority, facilitates access at a show. It’s a simple and declarative statement, “I’m with the band…” Leaving the Red Owl (forever known as ‘Furry’s Red Owl’ by me and David) I felt that I truly was that…but better and more special. I was with Furry Lewis.

At 5:10 the next morning, I awoke to hear the clatter of pans in the kitchen downstairs. My wife, Dianne, gave me an “is this necessary” look. I said nothing. Closing my eyes, I went back to sleep. When I opened them again it was 7:35 and the ambrosial aroma coming from the kitchen was as wonderful as it was unusual.

Walking into the kitchen, I found Furry bustling around, wearing one of my wife’s aprons. “You May Kiss The Cook” in large, red letters was the legend on the front. I said not a word. “Ain’t gonna be no grits in them greens. I washed ’em in twelve waters. Yes sir, a right-smart a waters…”

Later it would be explained to me that greens had to be thoroughly rinsed (in a ‘right-smart’ – a lot – of ‘waters’) to wash away the fine sand endemic to such as leeks, greens and the like. And indeed there were no grits in them greens. They were delicious. Spiced with cayenne, properly greasy from the fatback (“if you don’t use nothin’ but natural lean – you can’t cook no good greasy greens” as the tune goes), they were a hit. The cornbread was perfect. And David Calvit brought a gumbo, made from an old family recipe. A true feast.

[Note to readers – if there is interest in the recipe for the greens and/or the gumbo, hit the Comment button and let me know. I’ll append it in the next post…complete with metric conversion for y’all in So. America and Europe. AB]

Posted Tuesday, September 22, 2009

Gathering the Samurai…Sleepy John & Hammy

Brownsville, TN lies east of Memphis, just off Interstate 40 – The Music Highway. In 1999, (holyshit…a decade ago??) I took the exit to Brownsville on my way back to Nashville from Memphis. I was looking for a right-hand road.

It had been almost 20 years since I had seen Hammy Nixon, more than two decades since I’d seen Sleepy John Estes. By that time (’99) they were both long gone. I last encountered Hammy on Sept. 17, 1981 when, as a pall bearer, I sat next to him at the funeral of Furry Lewis. Rufus Thomas sat on the other side of me. An Oreo Sandwich, book-ended by musical greatness. Knox Phillips (Sam’s son) was in the audience, Jim Dickinson may have been there as well. Sid Selvidge and Lee Baker, torch bearers and Memphis musical luminaries, sat behind us. Hammy spoke, as did Rufus and others. I did not. Cowed by the august company and fearful of uncontrolled sobbing, I sat mute. One of my biggest regrets. But that’s a story for later.

John and Hammy lived near each other in Brownsville. Squalor doesn’t come close to describing their situation. Steve Tomashefsky of Delmark Records attended John’s funeral in 1977 and described to me what he saw. Run-down, falling to bits, disheveled, were just some of the words I heard from him. Children with lineages of questionable origin ran about. It was said that Hammy’s wife may have been John daughter, or vice-versa, or not. Who knew. But above all of this poverty and squalor rose the poetry of John’s lyrics and the power of Hammy’s harmonica.

The two partners had performed all over the world. They were the only members of the Caravan whom I sent to the Molde Jazz Festival who went directly to Norway, without having to stop in Washington, DC to undergo the “passport routine” (a routine I’ll describe in detail in a later post). John continued to compose and recorded for Delmark Records until very late in his life. His works, most recorded for various “race” labels from 1929 to the early 40’s, were covered by many popular performers. These ranged from various flamboyant American and British rock stars to the careful and poignant Ry Cooder.

John lost his sight in the 50’s and depended on Hammy to shepherd him about. His disability further deepened the bond between them and Hammy was always attentive to John’s needs. John suffered from a blood pressure disorder which caused him to nod off on occasion. The moniker ‘Sleepy’ was given him in the 40’s and it stuck for life. Hammy never used the nick name and always referred to him simply as John (I can hear him say it as I write this…).

John was fascinating to talk to. His conversation bespoke his poetic bent and made it a joy to listen. I remember sitting with him on the tour bus shortly after he and Hammy had returned from a series of overseas concerts. How was it, John? “I traveled and rambled far from home. Met peoples speaking a language I have never known.” John’s poetic style of speech was such that, when he spoke, all the other Caravan members listened. He was treated with a reverence and respect unique among members of the group. Hammy, on the other hand, was more “one of the boys.” No one ever thought twice about giving him a verbal jab and he endured it all with constant good humor.

Hammy was a large man, ample around the middle. He loved to eat. Anything left on a plate after lunch was fair game to Hammy. Backstage, he hoovered the cold cuts and fried chicken. He also suffered form considerable flatulence (yeah, well I’m terribly sorry – you’ll get past it…). He had ‘required seating’ near the front of the bus and more than once during a tour, a groan would go up from someone followed by a “Jesus, Hammy!” The front door of the the bus was flung open as we sailed down the highway at 65 mph. Never seemed to bother John, though – a fact that further strengthened the bond between them…at least, I’m sure, from Hammy’s perspective.

The road, to John and Hammy, as for many of the Caravan members, must have seemed like a Five Star vacation. Not only was there the adulation and attention, expenses were covered, there was a copious amount of liquor (not something that either John or Hammy particularly indulged in) and clean sheets and plumbing that always worked. Off the road, things were a bit different. John’s Delmark Records obituary noted, “However, like many artists, he had distinct public and private selves, and the poverty and frustration in his home life have spelled out a great American tragedy.” None of this want, however, marred John’s persona or performance. Articulate and witty, when ‘the dozens’ were played on the bus, and the ball tossed to John, hoots and hollers went up, “…Whatcha gonna say to that, John!!” Everyone hung on his response and whistled and clapped as the line hit home.

[Below are John and Hammy performing Corrina Corrina in Japan in 1976, the year before John’s passing. Hammy is playing harmonica and kazoo (!).]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vEZ3bdPRONg (deleted)

Posted Wednesday, September 23, 2009

Bukka White – and the National Steel. The ‘last’ Samurai

Booker T. Washington “Bukka” White was born in Cleveland, MS in 1905 – or in Aberdeen, MS, or…? No one seems too sure. But it’s a minor matter. What’s important is what he gave the world after those humble beginnings, where ever they may have been.

Bukka’s ‘instrument of choice’ was the National Steel Resonator Guitar, manufactured in quantity in the ’20’s, 30’s and ’40’s (and, to a lesser extent, to this day) and could be had from the Sears Roebuck Catalog for about $4.50, back in the day. Favored for its volume in the days before electrical pickups, the National could easily be heard above the din of a juke joint or picnic.

I first met Bukka White in 1972. “Bukka? He’s not here, He’s at his office…” His wife directed me to Leath St. a few blocks away. There, in the shade, against the brick wall that was one side of the Triune Sundry store, I found Bukka. He was sitting on a plastic chair. Next to him was a wood crate that held a cooling quart of beer. Scattered about sat three or four admirers. Bukka was holding court. I introduced myself and explained the purpose of my visit, to put together a group of Memphis Blues musicians to tour the country. Bukka was cool to the idea and visibly skeptical of just who the hell I was. Some white boy with a Bright Idea. He’d heard a few of those before. “If the money’s right – and I get it in front – maybe so…” That was extent of his commitment to the project.

“Okay, good enough for me. Let’s see what we can do.” We shook hands.

In the late ’30’s Bukka had done time at the notorious Parchman Farm Prison, a/k/a The Mississippi State Penitentiary. His daughter, Irene Kertchaval, told me the story. She said he won money in a crap game. The man he won it from refused to pay. Words were exchanged, the man reached down, Bukka pulled out a gun and killed him. Next stop, Parchman farm.

Parchman was less about punishment (and even less about rehabilitation) than it was about business. The ribbon-wire-enclosed ‘camps’ – as they were called – housed a tightly segregated population and sat amidst some 20,000 acres of cotton fields. These fields were worked by the general population and produced millions in state revenues. Established in the late a 1800’s, by 1914, Parchman was single biggest business in the state of Mississippi. It was still big business some 20+ years later when Bukka arrived to serve his time for manslaughter. His crime, being a black-on-black violation, did not draw a heavy sentence and, with the help of his guitar and talent, he was paroled after serving four years.

The racial element of justice, as dispensed in pre-mid-century America, was illustrated in high relief by an incident related to me by my friend, David Calvit. He grew up in Louisiana during the period. In 1949, as a teenager, David was summoned to court for a traffic violation. Waiting to be called, he sat watching the judge deal with the docket. A case involving the knifing of one black man by another was called and the victim took the stand. “How long was the blade on the knife that the defendant used to stab you?” the judge asked. “Uh, ’bout five inches, Your Honor.” The judge continued, “And how far into you did he stab that blade?” The victim looked at the judge, ” Uh, ’bout four inches, I reckon.”

The judge banged his gavel. “Twenty dollar fine. Five dollars per inch. Next case.”

Black or white, in those days the distance between ‘justice’ and ‘equity’ grew, it seemed, apace with latitude. Vernon Presley, father of Elvis, also served time at Parchman and may well have been there at the same time as Bukka. Their paths probably never crossed due the ‘separate but equal’ nature of their surroundings. Vernon got two years for “uttering a false instrument” – he altered the “$2.00” to “$3.00” on a check given him in payment for a pig. The issuer of the check was a local (Tupelo, MS) big shot who sought to make an example of this dishonest ‘cracker’.

My relationship with Bukka was slow to develop but eventually grew into a friendship. Early on, he displayed himself to be a man of his word. And he expected the same in return. He never had to be reminded what time the bus was leaving, when he had to be on stage or how long a set we needed. If we had a 5:00 AM departure for the next gig, he was the first man aboard.

Bukka and BB King were first cousins. In 1975 I helped organize a concert at Western Illinois University in Macomb, IL. The show consisted of Bukka White, Willie Dixon, Muddy Waters and BB King (whew!!). Either Willie or Muddy (I don’t remember which) had played Detroit the night before and had stopped in Chicago at 5:00 AM to pick up master harp player Carry Bell, just to add a little ‘weight’ to his set. I have never seen musicians so psyched to play a gig as these guys were when they showed up. Bob Margolin, Muddy’s guitar player for almost a decade, remembers it to this day – ask him, he’s on Facebook, that playground of the middle aged (I’m there, too…) or his website, bobmargolin.com.

Bukka opened the show, followed by Willie, then Muddy and BB closed. The show started at 8:00 and BB finally came down from the stage at 1:00 AM. There were some 3,500 people in the audience, and NO ONE LEFT. At the close of the show, BB called Bukka up to acknowledge him. Bukka grabbed the mic and began to talk. He reminded BB of his first guitar, a Stella, given him by Bukka.

“You remember, B, you was so little, next to that big red Stella.” There was absolute silence. BB was looking at the tops of his shoes. His eyes were filling. He looked, for all the world, like a nine- year-old boy, standing on that stage. “Yeah…I sure do remember.” he finally said, and threw his arms around Bukka. The audience erupted.

With the addition of Bukka White, the core group that comprised the Memphis Blues Caravan came to be. Others would rotate through, some on a regular basis, some but once. They would include the likes of Memphis Ma Rainey, Mose Vinson, Madame Van Hunt, Sam Chatmon, and others. We’ll be dealing with each, at various times, as the story continues.

[Below is Bukka’s “Fast Streamline” – background music for a wonderful short by someone named Shukowinz.]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fgQudd8zBSc (deleted)

Posted Wednesday, September 23, 2009

Hit the road…but why?

Why should I do this – why get involved in a task that offered a ton of work with little reward? Was ANYBODY going to get rich behind this? Probably not. My fellows at the agency had a finite amount of time to devote to doing what we did. We booked shows – each one of which would occur once in an eternity and then we had to do it all over again. Booking the Caravan would consume resources…of time, of money and involve an ‘education’ process to boot. It was much easier to book dates on ‘popular’ acts, (the forgettable and forgotten Mason Proffit, or Crow, or the nascent John Denver), than on a bunch of geriatric Blues musicians. Returning from Memphis, my first sales job was with the principals of Schon Productions, the agency I worked for. And then, with my fellow agents. We, all of us, worked on commission and the twenty minutes spent on ‘selling’ a date on, say, Crow, versus the hour or three to do the same for the Caravan, could not be ignored. To his great credit, Rand Levy, the agency principal, ‘got it’ and gave his okay.

Having secured commitments from the agency and the musicians who would eventually comprise the last, and only, touring ensemble of classic American country Blues, it was my job to get on the phone, start spreading the gospel and excite commercial interest in the entourage.

The first and most logical place to start, I thought, were colleges around the country. The reaction was almost uniformly positive and, God bless them, the offers started trickling in. ‘Trickle’ being the operative word. Again, (and again) the wisdom of this undertaking came under scrutiny. And I (we) had to closely examine the reasons for doing this. On some strange level, unarticulated in my own thoughts, a firm resolve formed. I thought about what I had seen and heard over my week or so in Memphis. I thought about what I felt as a 9-year-old and as a young man, listening. “We gotta do this…” was all I could muster to rejoin the doubts and concerns expressed by my peers. At that stage of my life I didn’t have the inner dialogue, or the experience, necessary to give voice to what I truly felt.

The members of the Caravan lived hard, shitty lives full of poverty, alcohol and violence. They had persevered through crushing disappointment, been fucked over countless times. Where were the royalties? Where were the gigs? Where, oh where, was the fucking money? In the mail? Not hardly.

In the early ’60’s a number of the members had enjoyed a brief moment of recognition, a bit of money, some notoriety. And then it was back to pushing a broom or moving furniture or driving a truck. When Jagger and Richards first met Muddy Waters, he was standing on a ladder, painting a wall at Chess Records. And he’d had HITS. So why did these guys bother? What made them keep doing this thing so full of promise and disappointment? They had no choice. Like Mr. Hooker said, “It’s in ’em and its gotta come out.”

As mentioned before in this scrivening, the Blues is as self conscious as a newborn. The root of its power lies in the unintended nature of its artistry. Every member of the Caravan played for themselves, first. The audience was second. The art and magic that came out of them and spilled across the stage was almost accidental. I have a tape of a show where Furry Lewis breaks down on stage (it happened more than once, believe me). He can be heard, clearly sobbing and then speaking to me, after I rushed from the wings. “I done broke down…what should I do?” The moment had gotten the best of him, and of the audience. His were not the only tears shed that night.

Tolstoy said that art is emotion, transferred from one person to another. True art has the added power of accident – or at least lack of premeditation. Furry never intended to be overcome by the emotion fueling his performance. He usually left the stage dry-eyed. But the emotion was always there, it was in him – and it had to come out. Occasionally it got the best of him. Watching a performer who weeps at the same point, in the same song, night after night (Vegas has a couple…) may be affecting. But profoundly moving? NFW.

On some level, back then, I knew I wanted to be in the Profoundly Moving Business. Like our Japanese friend of an earlier post, I wanted audiences to be given the chance to be Very Splendid.

“We gotta do this…”

Powered by a small group of zealous agents at Schon Productions (me, Gary Marx, Sue McLean & Randy Levy), the trickle eventually became a steady stream and the first tour took shape.

Posted Sunday, September 27, 2009

Gonna shake ’em on down…

Once the initial dates were booked, the job of logistics became daunting. We had to move some twelve performers, a road manager and various pieces of equipment, from Memphis to the first date and then on to the next.

Flying the dates was out of the question as our budget was tight at best. We were not dealing with ‘rock star’ money but we had the same problems and requirements as a major rock tour. I decided that the best was to move the group was by chartered bus and struck a deal with Greyhound to provide equipment and drivers. Our first two tours were done in leased commercial coaches. This proved to both unwieldy and expensive. It also did not provide the ‘comfort factor’ needed for a prolonged stint on the road. By the third tour, we had wised-up and found a company out of Nashville who specialized in tour bus leasing and provided equipment with lounges, bunks, a galley and head. The real deal. They also provided a driver who would be with us for the duration of the tour and who became, usually by the second night, a huge fan AND a member of the family. In the ‘destination window’ up on the front of the bus, facing oncoming traffic, we put a sign that read “Heaven” – and we hit the road.

In addition to the expense of transportation, we had salaries, Per Diem, lodging, “incidentals” (i.e. beverages) and the like to deal with. Hotel rooms had to be booked, set orders and lengths had to be determined (and in some cases, negotiated), egos assuaged, etc. the job became more complex by the day. And it all had to be done before we played the first date – and that first date was in Chicago. Lucky for me, I had a well connected friend who eased the process considerably.

That friend, David Calvit, (he of the greens story) owned a company in Minneapolis called Corporate Travel. The company specialized in just that, corporate travel. Blues performers were about as far from his usual clientele as you could get.

Our first date was in Cahn Auditorium at Northwestern University. That’s Chicagoland. Trying to find reasonable lodging wasn’t just a chore, it was an impossibility. Eight rooms at bargain rates were not to be found. I had resigned myself to the probability of a night in Gary, IN and the resultant hour and a half ride to and from the gig. In a causal conversation with my friend, I mentioned our plight. He listened quietly. “Furry is going to on these dates, right?” he asked. “Of course.” The conversation ended.

The next day he called and told me we had the rooms we needed at the Lake Shore Holiday Inn on Lake Shore Drive. From trips to Chicago I knew that this was Holiday Inn’s premier property in the city.

“Sounds great…but we can afford the wood.” I had visions of $130 plus per night per room (in 1973, a lot of money). I was thinking more like a no-tell in Elgin or maybe the same in Gary.

“Your rate is $35.00 per night.” Holyshit.

Arriving at the hotel from Memphis, the night before the show, the marquee facing Lake Shore Drive was ablaze with the words “Welcome, Memphis Blues Caravan.” We checked in to find real rock-star service. A complimentary fruit basket (with a hand written note to each artist) was in each room. Furry Lewis had his own room. It was the penthouse suite, complete with panoramic views of Lake Michigan and the Chicago skyline.

Posted Monday, September 28, 2009

Alcohol & Violence – “…knowing that most things break”

“For soon amid the silver loneliness

Of night he lifted up his voice and sang,

Secure, with only two moons listening,

Until the whole harmonious landscape rang –“

Alcohol and violence were a constant in the lives of virtually every member of the Caravan. It was not unique to them, it was a byproduct of one other constant, poverty. If your life circumstances are shitty, alcohol provides an escape from those circumstances. Not that all poor people drink – or drink to excess. Far from it. Problem is, when some people drink, shit happens. And usually it’s not the shit that people want. Believe me, I know. ‘Nuff said.

Booze and music have always been co-ingredients in a roaring good time. Musicians have had a firm grasp on the power of the interplay between those two elements as well as an appreciation for the transformative escape provided by both. From the old song lyric, “If the river was whiskey and I was a diving duck, I’d dive to the bottom and never would come up” to the modern song title, “There Stands The Glass” – it’s the same lick. Alcohol takes us someplace else. Away from where we are. Music does the same. Together, they can be a veritable magic carpet. But sometimes that carpet lands on the wrong side of the wall.

Bukka White was the only member of the Caravan to have served time in a State Penitentiary. None of the members, however, were unfamiliar with jails or the police. Bukka’s crime was manslaughter and he would lager confide that his visit to Parchman wasn’t his only experience behind bars. He had spent time also in the Shelby County Jail in Memphis for a similar crime. He never gave a definitive figure on the number of men he had killed. It was at least two, possibly more. He claimed that each incident was in self defense and that he ‘hated to do it.’ Was he, or his victim, sober when these things happened? Probably not.

John ‘Piano Red’ Williams also had brushes with the law. While he never admitted to having been arrested, his conversation was rife with recollections of violent encounters. I remember one exchange in particular, sitting with Red at the dining room table in my house in Minneapolis, where red was engaged in one of his winding stories of stream-of-consciousness descriptions of incidents experienced during his 80 or so years.

At this telling he described an encounter with a ‘devilish rascal’ who had crossed him (hummm, was anyone having a drink?). Their exchange escalated into a full -blown confrontation, forcing Red to pick up an axe handle. At this point in the story, he asked if I knew how to ‘han’el’ someone through the use of such a weapon.

“Ah, no…”

Pleasant and friendly, Red continued in his innocent-sounding, high-pitched voice. “Well, first you him in the one arm. Him sharp, comin’ down at a angle. You break they arm. Then you him on the other side, and break they other arm.” Red paused, making sure that his lesson was getting through, perhaps expecting a question. “Then you take the axe han’el,” he continued, in the same sweet voice, “and you hits ’em in they haid.”

Joe Willie Wilkins, a pacific and gentle soul, told me of a call he got from Muddy Waters in the late ’50’s informing him that he (Muddy) was was sending his guitar player at the time, Pat Hare, back to Memphis. The instructions were that Joe was to arrange for Pat to ‘lay low’ for a while and not return to Chicago until he was sent for by Muddy. Pat had recorded for Sun Records in its early years and released a side ominously titled “I’m Gonna Murder My Baby” (re-released on Rhino in 1990). A few years later, in a jealous drunken rage he killed a woman in Chicago and was under investigation for the crime, prompting the call from Muddy. Joe related that this was not the first time such a thing had happened to Pat Hare.

Hare’s name was familiar to me as I remember reading an account of his crimes in the local paper years after his Memphis visit. Auburn ‘Pat’ Hare killed a woman in Minneapolis under similar circumstances. He also killed a policeman sent to investigate. Hare was roaring drunk at the time. Joe Willie allowed as Pat, sober, was a quiet and unassuming guy. Drunk, he was a homicidal maniac.

Auburn ‘Pat’ Hare died in Minnesota’s Stillwater State Penitentiary in 1980. Had alcohol not taken him there, who knows where or when he would have died.

Whiskey and fried chicken fueled the Caravan in its years on the road. From management to performers, Jack and Jim were constant companions. Looking back through the haze, it’s a wonder nothing more serious occurred than a pulled knife and some threatening words (both courtesy of Furry, but more of that later).

No injuries, no cops, no blood.

With a nod to E. A. & Mr. Flood…

Posted Friday, October 2, 2009

Rolling Through The Night –

Sometimes, when contiguous dates couldn’t be routed, we were forced to make a ‘hop’ of several hundred miles to the next engagement. These were largely done overnight so that arrival would put us in at least six or seven hours before showtime. Generally, these overnight adventures were the exception. But we were not the Rolling Stones. We couldn’t pick and choose which dates we would play. We took what we were given and made the best of it.

On nights such as these we would leave directly after the show and rack up a couple hundred miles before stopping for a late snack. Of course ‘Snack’ was a total misnomer for what happened at the hands of the Caravan members in a diner. These guys could eat.

One night we played Marion, Il, a town situated in the southern part of the state. The following night we were playing Charlottesville, VA, some 800 miles away. Leaving Marion at about 11:00, we eventually pulled into a truck stop in northern Kentucky called the Cross Keys. It was close to 1:00 AM. The establishment lay at the branch of Interstates 24 and 64. Ten miles before we arrived, the CB in the bus crackled with female voices promising all manner of delights. Each lady had a ‘handle’ descriptive of the services provided and were actively soliciting congress with truckers inbound to the Cross Keys. Interest level on the bus increased with each mile.

The Cross Keys was huge. It held about four acres of 18 wheelers – parked one after the other. The whole scene was illuminated by mercury vapor lamps perched high atop poles scattered about. The air was gray with diesel exhaust. And hopping from cab to cab were the hookers.

We pulled up to the front and walked single file into the restaurant potion of the complex. Heads, covered in Peterbuilt, Mack and Freightliner hats, turned as we made our way. Conversation stopped. For a moment, I felt like we were from Mars and had just made landing on some strange, bizarre planet. Slowly, we settled into booths and tables. Conversation resumed, heads turned back to coffee, biscuits and gravy or whatever. A waitress approached, “What kin ah gitcha, hon…?” she said to Furry, sitting at the head of a table.

We ate. And ate. We drank coffee. We paid the check. We left.

Walking back to the bus, past the hookers flitting from cab to cab, I was about to board when one of the ladies hopped down from a cab-over-Pete parked next to us. As the driver closed the door, I noticed what was written on its side, “Sawyer Transport”. And underneath, in italic script, “Truckin’ For Jesus.”

Stomachs full and back on the bus, we high-balled out of the Cross Keys, disappearing into the eastbound darkness. Our next stop would be somewhere past the Smokey Mountains in the first rays of dawn.

The post-show adrenalin had pretty much dissipated and the hearty fare began to have a sedative effect. By twos and threes, the members ambled off to their respective bunks and fell asleep. Aside from myself, Furry and Red were the last two left conscious in the forward lounge. Furry was the first to drop and announced that he’s like to stretch out. I helped him back to his bunk. Red sat slumped in a Captain’s Chair, his great stomach taut against his T-shirt. Coe College it read. He wore it everywhere. With his hat still on his head, he closed his eyes and snoozed quietly. It was 2:40 AM.

I climbed into the jump seat above and behind the driver. Looking down, I could see the soft green glow of the instrument lights and ahead, through the broad front window of the Silver Eagle, our headlights pushed down the Interstate. I asked the driver how he was doing. “Just fine…” Did he ever get tired on these long overnight runs? “Nope. Driving is what I do.”

Okay…

The radio was tuned to KAAY out of Little Rock or, alternatively, to KDKA, the nation’s first commercial radio station, out of Pittsburgh. These were the days of Clear Channel AM radio and the two megawatt giants came in like a local station. As a young man in Minneapolis, driving my father home form work on winter nights, we would listen to KDKA’s National News at 5:00 PM. And in the mid ’50’s, XERF, nominally out of Del Rio, TX (but really out of Ciudad Cohilla, Mexico) would blast 100,000 watts of Rock ‘n Roll to eager young ears in the Heartland.

Music played from the radio. The driver and I listened in silence.

After a time, I slid out of the jump seat and stood in the stairwell leaning hands-on-chin against the Silver Eagle’s broad, padded dashboard. Half a moon shown in the southern sky and the dark fields rolled on, reflected in a faint silver luminescence. America passed under my feet. Mile after mile. Vast, didn’t come close. Years later at various times, I would tell newly arrived British musicians, as they made ready to embark on a first US tour, “Gentleman, you are about to have a new appreciation of the word ‘distance.'”

The music from the radio played not just in our ears that night. It played in the ears of the thousands who listened, busy with business that kept them up as the hours passed. It was a tie that bound all; familiar, comfortable, entertaining. The music spoke to some, stirred memories or emotions in others, and assured the rest that they were not alone. American music, sailing through the night air.

And here they were – a bus-load of dinosaurs. Country Bluesmen, the last living relics and purveyors of one of America’s greatest musical traditions. Shining the light, declining the bushel. On their way to the next gig, just 800 miles down the road.

Posted Tuesday, October 6, 2009

A Day In The Life –

The Caravan was, in many respects, a party on wheels. It consisted of a group of co-conspirators who both enjoyed each others’ company (for the most part) and shared a commonality of experience unique to a very small group – i.e. they were American Blues singers.

The day would begin with breakfast, usually a hearty affair heavy on the fried side of the menu. This would occur anytime between 5:00 and 9:00 AM depending on when we had a ‘bus call’. The ‘bus call’ was a previously agreed upon time signaling the departure of the bus for the next gig. This call was inviolate and could not be missed. With very few exceptions, it was never a problem – most of the Caravan members were early risers regardless of when they got to bed the night before.

After check out and settled on the bus, the Caravan fell into a routine. Each member sat in their respective seat in the lounge of the bus (by the second date, each had claimed a favorite) and entertained each other as the miles rolled past.

One of the favorite pastimes was to play “the dozens” a rhyming put-down game where one member tried to top the other with a well-aimed jibe or an answer back in kind. The origin of the name of this game was something I wondered about over the years. Anyone I asked, including members of the Caravan, had no idea. The response to a casual insult was many times a curt “don’t do me no dozens…” It wasn’t until years later that I would learn where the term originated.

In the antebellum South, when slaves became old or enfeebled or otherwise damaged (they were chattel), they were put in groups of 12 and sold as a lot at auction. Being ‘in the dozens’ was a situation to be avoided at all costs and carried with it a sense of shame. In modern day, it had been softened to indicate mere discomfort at being “one-upped” by someone else. The king of dozens was, as mentioned earlier, Sleepy John Estes, the poet of the Blues.

At about 1:00 or 2:00 in the afternoon the call would go up to stop at a ‘chicken store’ to get some lunch. Simultaneously there would be a request to stop at the ‘whiskey store’ for fortification against the chill of the coming evening. The party had begun.

On reaching the gig, out first stop was the hotel. Check in was always an experience, both from the reaction of the desk staff, to the process of getting everyone sorted out and into their respective rooms. Red and Furry were ‘roomies’ as were the drummer and bass player from Joe Willie’s band. Old partners for years, John and Hammy bunked together as did Stack and Joe Willie. Bukka and Clarence Nelson (Joe Willie’s guitar player) had single rooms, as they desired.

After everyone was in their respective rooms, I would go over to the venue, Sound and lighting had to be checked out to be sure contract rider demands for production were met. I would also meet with the producer to see if there was any last minute press that had to be done (this was in pre-cell phone days when none of this could accomplished en route, as it can today). Soon it was time for a sound check. This would require the presence of Joe Willie’s rhythm section – Joe Willie and Stackhouse, who were ‘stars’, didn’t have to involve themselves with these details. Drums were set and mic’ed, lighting cues were discussed, the band would run through a couple of tunes to set levels and any last minute details were attended to. All this was usually finished about an hour before “doors” (when doors were opened and ticket holders where let into the house). As the auditorium filled, I went back to the hotel to round up performers and head back to the venue. We usually arrived about ten or fifteen minutes before show time.

Some promoters felt this was a bit too close for comfort but they never had cause for concern. The Caravan never missed a curtain time. If we were supposed to hit at 8:00, we hit at 8:00.

The ‘opener’ for the Caravan was always Piano Red. He took great pleasure in his constant reminders to the rest of the group that it we he who had the hardest job of the lot. He also suggested that any enthusiastic response that the rest of the Caravan might receive was due largely to the warm carpet that his performance spread for them. He was, more often than not, at least partly correct. Bukka White followed next, then Furry Lewis. No one wanted to follow furry.

After Furry’s set we generally had an intermission and then opened back up with Sleepy John Estes and Hammy Nixon. They were followed, in many instances, by Ma Rainey (Lilly Mae Glover) backed by Joe Willie’s band. Joe Willie and Stackhouse joined the band next and at the end of their set, went into ‘The Saints’ and were joined on stage by everyone in the Caravan.

After the show, it was party time in earnest. Backstage was usually clogged with people, a great many with guitars in hand, asking questions about everything from tuning techniques to the brand of whiskey preferred by respective performers. It was at this time that I had to be on my guard as well-intentioned youngsters badgered the performers with questions. The problem came when a few would try to cut one or two of the performers from the pack (usually Furry and/or Bukka) and spirit them away to some house or apartment for an after-hours songfest. Both performers were always game for an adventure of this sort but I had learned from experience that this meant trouble.

Though probably well intentioned, the hosts of these clandestine get-a-ways, did not have the best interests of the performers at heart. Fueled by copious amounts of booze and God knows what else, these get-togethers had the potential for real havoc. We didn’t need any trouble, “a thousand miles away from home, standing in the rain…”

After the backstage shenanigans, we went back to the hotel and usually gather in one anther’s rooms. The guitar would get passed from hand to hand, the bottle of Jack Daniels would slowly drain and by 1:00 or 1:30 AM, it was lights out.

The next morning we got up and did it all over again.

Posted Wednesday, October 14, 2009

The Squabbles…

Like any extended family, not everyone got along. The major friction in the group lay between Furry Lewis and Bukka White. These two had known each other for years and lived just a few blocks apart. Their paths had crossed professionally and socially countless times and they had been booked on selected dates together before the Caravan was organized.

After one of these dates, the two were at an airline ticket counter somewhere in Colorado preparing to fly home to Memphis. Furry recounted the following story to me. Furry kept his wallet in his hip pocket, wrapped in a thick rubber band. Evidently he had to open it at the counter for some reason. After his business was transacted, he left. Bukka was in back of him, next in line. A few feet from the counter, Furry realized that he had left the wallet and returned for it. According to Furry, when he got his wallet back there was $100 missing.

Ever since that day, Furry had ‘a problem’ with Bukka. Whether there was any truth to the story, I find hard to believe. Bukka may have been many things, but he was not a thief. Cataracts had laid claim to Furry’s eyesight and a mis-count was entirely possible. The true source of the problem lay more in the realm of professional jealousy and Furry’s covetousness of the spot light than any overt larceny.

One afternoon on the bus the rancor came to a head. Furry was sitting about two seats in front of Bukka. Evidently, there were some words exchanged between the tow of them. All of a sudden I heard someone shout my name. “You better get back here quick!”

I turned and headed up the aisle. There was Furry, standing by his seat with his back to me. His broad-brimmed fedora was on his heard and his cane in his left hand. In his right hand was a knife. I rushed up to him and asked what the hell was going on. Furry turned to me and said, “I ain’t gonna say a word to that motherfucker, I’m just gonna cut his goddam head off!”

Bukka was smiling. “You just a silly old man” he said to Furry. I took Furry by the shoulder and asked him to sit down. He did so immediately. “Nobody gonna talk to me like that sombitch does” he said. I asked him to pocket the knife. He did so, slowly. Silence. Finally, Hammy Nixon, sitting across the aisle broke the ice. “No place here for that kinda shit. ‘Sides, I hear Bukka be jealous of you cause you so good lookin’” everyone laughed. Including Furry. Bukka stared out the window.

Whew…

Later, I would talk to Bukka to find out what was going on. He said he had told Furry that he thought it wasn’t such a good idea that he (Furry) bother other performers while they were on stage. Furry had a bad habit of suddenly appearing from the wings sometimes during someone else’s performance. He would wave his hat in the air and do a little dance. Audiences generally went nuts. That was all Furry needed. Any encouragement from an audience would cause him to run a routine into the ground.

I and others had discussions with him about this in the past. He always countered that he was “just trying to help the show.” Try as we might to explain the situation to him, he was like a bottle rocket backstage. Unpredictable. But fortunately not very fast. Eventually, someone from Joe Willie’s band was assigned “Furry duty” during the show so that incidents could be kept to a minimum.

By far the most frequent victim of Furry’s attention-grabbing was Memphis Ma Rainey (Lily Mae Glover). Ma’s performance was theatrical and florid and always got a great response. Furry, however, had no respect for her, either as a person or as a performer. “She just an ol’ barrelhouse woman. Never cut no records. Made more money on her back than standing on a stage…” After a show one night when Furry had (again) interrupted her performance with his ‘hat dance’ she let him have it. Back in the dressing room, she threatened to “knock you on your goddam ass if you ever try that again!” And she was more than capable of following through. In her younger days, both before and after traveling with the original Ma Rainey, she would occasionally supplement her income rolling drunks on Beale Street. A sweet person at heart – but more about her in a later post.

The squabbles. Rock stars or country Blues performers, everyone had an ego. It came with the territory.

Posted Tuesday, October 27, 2009

Furry Lewis – and some ‘religious songs’…