A timely reminder of the bloody anniversary we all forgot

A timely reminder of the bloody anniversary we all forgot

By Robert Fisk, Sunday 28 December 2014

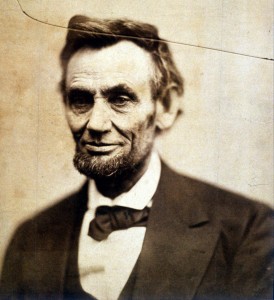

Every month, my London mail package thumps on to my Beirut doorstep with An Cosantóir inside. It’s the magazine of the Irish Defence Forces – surely the glossiest-paged journal of any army, let alone one of the smallest military forces in the world. But among its accounts of Ireland’s UN missions abroad – think Golan, for example, with Syria’s civil war crashing around Irish soldiers – almost inevitably each month, there’s a piece of history we’ve forgotten. For while the start of the Great War of 1914-18 has been commemorated to the point of spiritualism these past 12 months, who remembers that this week we enter the 150th anniversary year of the end of the American Civil War?

In US history, it is a profound event that we should all remember; here, after all, lie the original bones of the Union, its victory consecrated among some of the units whose soldiers were sent to their deaths in Iraq in 2003, its brutality ghosted into the future narrative of American military records, its equalities reflected in the large number of black soldiers who died in present-day Mesopotamia. But for the Irish, too, the civil war of 1861-1865, is a sombre anniversary.

They reckon that 210,000 Irish soldiers fought in British uniform in the First World War, and that 49,300 were killed. Yet almost as many Irishmen fought in the American Civil War – 200,000 in all, 180,000 in the Union army, 20,000 for the Confederates. An estimated 20 per cent of the Union navy were Irish-born – 26,000 men – and the total Irish dead of the American conflict came to at least 30,000. Many of the Irish fatalities were from Famine families who had fled the desperate poverty of their homes in what was then the United Kingdom, only to die at Antietam and Gettysburg. My old alma mater, Trinity College Dublin, is collating the figures and they are likely to rise much higher as Irish academics mine into the American Compiled Military Service Records for the regiments of both sides.

In An Cosantóir, the archaeologist and historian Damian Shiels, writes that the very first Irish soldier to die in the American war in 1861 was an Irishman from Co Tipperary, mortally wounded when his arm was blown off. Private Daniel Hough, of the 1st US Artillery, was a gunner firing a salute permitted by the victorious Confederates after the capture of Fort Sumpter, South Carolina, on 12 April. The second soldier to be killed in the same war died that night. He was Edward Gallway from Co Cork. Of the fort’s military garrison of 86 men, 38 were from Ireland.

The best Irish-born Union general of the war was 32-year-old Brigadier-General Thomas Smyth, a Cork man leading his brigade across the Appomattox river in 1865 in pursuit of Robert E Lee. Riding to the front line, a bullet fired by a Confederate sniper hit the left side of Smyth’s face, entering his neck and spinal column. He died on 9 April. “Less than 12 hours later Lee surrendered the Army of North Virginia to Ulysses S Grant…” Shiels writes. “The former farmer from Ballyhooly, Co Cork, thus became the last Union general to die in the war.”

As Shiels says, many of the Irish affected by the civil war were Famine-era emigrants, “for whom the war represented the second great trauma of their lives”. Take Charles and Marcella O’Reilly, who left Ireland in the 1840s. Their eldest son enlisted on the Union side in August 1862 and was joined by his father Charles in the New York Heavy Artillery more than a year later. Father and son were fighting side by side at the Battle of Cedar Creek in 1864 when the Confederates launched a furious attack. Shiels quotes a terrifying account of what happened, written by a comrade of both men in a style so familiar to accounts of the Great War almost exactly 50 years later:

“…Anthony Riley [sic] was shot and killed; his father was by his side; the blood and face of his son covered the hands and face of the father. I never saw a more affecting sight than this; the poor old man kneels over the body of his dead son; his tears mingle with his son’s blood; O God! What a sight; he can stop but a moment, for the rebels are pressing us; he must leave his dying boy… he bends over him, kisses him on the cheek…”

Just over five months later, Charles O’Reilly died of disease contracted in the trenches of Petersburg, Virginia. The loss of her husband and eldest son was disastrous for Marcella and her remaining children. In 1871, her property was seized by the sheriff and sold – an English-style misery that must have been harshly familiar to the widow.

The last known Irishman to have fought in the civil war was still alive in 1950. But memories were mixed. While 146 Irishmen were awarded the Medal of Honour in the war, the Irish Brigade lost heavily (although most Irishmen fought in non-ethnic units). If 25 per cent of the New York population were Irish – which accounts for the large numbers fighting for the Union – the rising casualty toll reduced the army’s recruitment. Two-thirds of the protesters in the New York Draft riots – following Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862 – were Irish. Which proves that romance has little place in history. And in Ireland, there is today not a single memorial to the Irishmen killed in that great conflict on the other side of the Atlantic – which preceded the other Great War, whose dead lie across the fields of the Somme and Ypres.

And a final blow of the trumpet of that last Great War, for which I must thank journalist Peter Murtagh. Captain Arthur Moore O’Sullivan, of the Royal Irish Rifles, from Co Wicklow – Amos to his friends – sent

up one of the signal flares during the Christmas 1914 “football truce” in the trenches of France. Alas, he was wounded in no man’s land three months later, and in April was killed in the hopeless battle of Aubers Ridge, where around 11,500 died. One of the Germans to survive was Corporal Adolf Hitler.

http://www.independent.co.uk/voices/comment/a-timely-reminder-of-the-bloody-anniversary-we-all-forgot-9947514.html or http://ind.pn/1y0UekK