Hook-nosed Jew vs. Mohammed cartoons: What’s the difference?

By Shoshana Kordova, Jan. 21, 2015 11:50 AM

You won’t be surprised, in these post-Charlie Hebdo days, to hear that there’s a controversial cartoon going around the Internet. I’m not talking about a French cartoon, but a drawing from 2012 by Brazilian cartoonist Carlos Latuff illustrating his belief that insults to Jews are derided by the West as anti-Semitism while insults to Muslims are hailed as free speech (see below).

It may feel uncomfortable to ask out loud whether we are upholding a double standard if we protest the publication of cartoons of hook-nosed Jews while supporting the publication of cartoons of the Prophet Mohammed. That, after all, is a question that could get people labeled “anti-Semites” or “defenders of terrorism.” But it is a legitimate question well worth addressing – even if we don’t all agree on the answer.

Some would have us believe that protesting cartoons perceived as anti-Semitic is a form of censorship, a way of inhibiting freedom of speech. But genuine freedom of speech is most meaningful when proponents of both sides of any given issue can enjoy it: Those who seek to publish stereotypical images of world-dominating Jews, and those who protest them; those who seek to publish cartoons depicting Islamic fundamentalists as “idiots” who fail to comprehend the true Islam, and those who protest them.

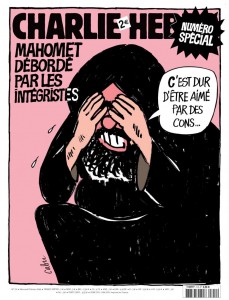

The cover of an issue of Charlie Hebdo magazine reads, ‘Mohammed overwhelmed by the fundamentalists’ and ‘It’s tough being loved by idiots.’

It ought to go without saying that such protests lose all legitimacy when they involve deadly weapons, or any form of violence. But if the violence has already taken place, there is no dissonance between objecting to an act of terror targeting cartoonists and objecting to a cartoon you find offensive. That’s not a double standard; it is the very embodiment of free speech.

In the West, not only Muslims, but Jews and Israelis, too, are occasionally the targets of a cartoonist’s pen. A 2003 cartoon by Dave Brown that ran in Britain’s The Independent showed then-Prime Minister Ariel Sharon devouring a Palestinian baby. The Israeli Embassy called the cartoon an anti-Semitic allusion to the blood libel that Jews eat Christian children. But the U.K. Press Complaints Commission approved the cartoon, accepting the argument that it was a satirical take on a Goya painting and targeted Sharon as a politician (not a Jew). It later won Britain’s 2003 Political Cartoon of the Year award.

More recently, Australia’s Sydney Morning Herald published a cartoon in July by Glen Le Lievre that showed a kippa-wearing man sitting on a chair emblazoned with a Star of David, remote control in hand, as he looked out over an exploding Gaza Strip during the summer’s 50-day war. At the time, the media were reporting that some residents of southern Israel were sitting outside to watch the air force drop bombs over Gaza. The Herald apologized after Jewish groups threatened a lawsuit, arguing that the cartoon was anti-Semitic.

Were either, or both, of these cartoons actually anti-Semitic? Even if there were an objective barometer that could determine such a thing, the answer would be irrelevant. What is relevant is the process that took place: Two publications decided to publish cartoons that were likely to cause offense; people did get offended, and lodged protests; one of the newspapers defended its decision and the other apologized.

And that brings us to the other side of the free press coin: the right of media outlets to choose what to publish. Just as protests against certain kinds of cartoons have come under fire lately as undermining free speech, so have the decisions by some leading media outlets not to publish the more controversial Charlie Hebdo covers, such as those picturing Mohammed.

There is a strong argument to be made in favor of publishing the cartoons, primarily that their newsworthiness outweighs any offense they might cause. But freedom of the press means, in part, that the press should have the freedom to decide what it will – and will not – publish. For many publications around the world, that meant running the cartoons, in some cases on the front page; for New York Times executive editor Dean Baquet, it meant refusing to print something he characterizes as “gratuitous insult.” Just as Charlie Hebdo exercised its right to publish what it deemed fit to print, so did the Times exercise its right to refrain from publishing what it deemed unfit.

The problem is that France, which has some of the toughest hate speech laws in the European Union and has made it illegal to deny the Holocaust, doesn’t actually offer its citizens full free speech rights. Outlawing hate speech may sound like a good idea, but when one kind of comment gets people lionized and another kind gets them jailed, all the arguments about the beauty of democracy and freedom of speech are shown to be nothing but worthless words. The excessive yet inconsistent restrictions France imposes on freedom of speech and religion make it clear that it is not the bastion of democracy it claims to be, and this patchwork liberty reinforces what in France are indeed well-founded suspicions of a double standard.

All of us, French lawmakers included, would do well to recall the words of U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, in a 1949 majority ruling overturning the conviction of a man whose pro-Hitler hate speech sparked a protest. “The right to speak freely and to promote diversity of ideas and programs is therefore one of the chief distinctions that sets us apart from totalitarian regimes,” Douglas wrote in Terminiello v. Chicago. “Accordingly, a function of free speech under our system of government is to invite dispute.”

Is everyone always going to agree on where to draw the lines, whether literal or figurative? That would be highly improbable, and the precise location of the border between satire and insult will likely serve as a rich vein of argument for decades to come. Let’s not shut down those arguments, whether by limiting freedom of speech or by dismissing questions about what embodies it and what undermines it. Instead, let’s follow Douglas’ suggestion and invite dispute, as long as it’s the sort that involves words and images rather than guns and bombs.

Shoshana Kordova is an editor at Haaretz English Edition.