Meditation on My Home in Lebanon

Meditation on My Home in Lebanon

By Frances Fuller, 21st February 2016

I made a mistake in my book. Let’s just say that I was wrong. In the epilogue of In Borrowed Houses I said that the little stone house around which my whole story revolves would outlive all of us. My actual words were: “It will be there when everyone who remembers this story is gone.” With so much confidence I said that. After all, its walls were built of stones a foot thick. It had survived a hundred and fifty years, enduring wars, earthquakes, occupation by wild creatures, and evolutions from home to abandonment, from abandonment to stable, from stable to home.

On Ash Wednesday, at a moment in which I felt a little glum anyway, I got the news from a Lebanese friend. The little house had been demolished. “Nothing but memories remain,” she said. It seems that someone with money to invest bought it to destroy it and build a hotel in that choice spot, with that lovely view.

It is surprising how much this hurts, and I am pondering the reason.

We spent a year finding it, studying it, asking for it, doubting, waiting. Then we spent two and half years shoveling manure out of it, replacing the door the wind blew off, dreaming about it, remodeling, cleaning, losing it, struggling to get it back, trying to be patient, insulating it, measuring for curtains, furnishing it and moving in. And then we lived in it for only two and a half years.

It was never ours; this is important to remember. Missionaries do not own anything in the country in which they serve. We were permitted to turn it into a home and live in it. This is an illustration of life on earth, where some of us are permitted to act like we own something.

Our neighbors admired it; our colleagues envied it; our young Lebanese friends invested in it time and love and dreams of what we could do there together. We even did a few of those things.

We were sometimes lonely there. Our first Christmas in the house was also our first in thirty years without any of our children with us. Trying with a heavy heart to decorate the Christmas tree all alone, I heard a knock on the door and there stood a young man, one with special affection for our eldest daughter. I think he was surprised by the unusual warmth of my reception, but he made me so happy by helping me decorate that tree.

Discovering ourselves in the middle of a battlefield, we erected a sandbag barrier just inside the graceful stone arch at the entry of the little room we called “the cave.” I’m not sure there was ever, anywhere else in the world, a wall of sandbags decorated in front with a table that was a work of art, holding a potted plant. We slept on the floor at the junction of this neat stack of sandbags and the stone wall, a privileged spot in a village holding its breath.

Discovering ourselves in the middle of a battlefield, we erected a sandbag barrier just inside the graceful stone arch at the entry of the little room we called “the cave.” I’m not sure there was ever, anywhere else in the world, a wall of sandbags decorated in front with a table that was a work of art, holding a potted plant. We slept on the floor at the junction of this neat stack of sandbags and the stone wall, a privileged spot in a village holding its breath.

In that little house I scrubbed the skin off my fingers, sang hymns and prayed, hosted crazy parties, was very sick and got well again, wrote stories, got scared, and in the end left it with my heart broken. Why did I think it could go on standing there on the hillside when I know that what the Lebanese want now, and deserve, is a bright new prosperous country?

In church on Ash Wednesday, during our pastor’s brief homily, I tried to listen but mostly thought about “my” house. Then standing in the aisle behind a line of people, waiting my turn to admit that I am a sinner and get ashes on my head, I thought that perhaps I am too attached to the world. I want to stay in places I love. I want them to stay in my life. Why, I wondered, do I care so much that the little house has been destroyed? Didn’t I leave it and let it go? Don’t I have now a bigger, better house? Why should it matter, when I know already I will never go inside of that little house again? Twice I have been to Lebanon in the past twenty years. Twice I have seen the house from the outside. I admit needing to tell myself on those occasions that it was only a house, because of the ache in my breast.

I am reminded of words from Khalil Gibran, Lebanon’s most famous poet, who also departed the country in pain, under difficult circumstances. He wrote that one cannot easily leave a place where he has suffered. I find that to be mysteriously true.

But my daughter Jan also sees a reason for my pain. She says, “It was a symbol of everything we loved about that place.” That could be it. We humans hang on to our symbols, sometimes after the real thing is gone.

As my pastor painted that cross of oil and ashes in the middle of my forehead, I was thinking that a symbol is only that and not the thing it stands for. The house is gone, but like the little black cross on my head, it is only a symbol.

The cross is actually a sign that is hated in many places I have been, because it reminds some people of ways our sins have hurt them. On my forehead where it survived only a few hours, it was a doubly appropriate sign of mourning, and I thought that night that it was also a brand. The way an animal might bear the sign of its owner, I was marked briefly with a sign that I belong to Christ who is pure and good and who, before he died, promised to prepare a “house” with space in it for me, so that I can be where he is.

So on Ash Wednesday I lost the little house in Lebanon but remembered that I have another that cannot be bought with anybody’s money or ever touched by a demolition crew.

But right now, as I write this, I realize that something is wrong with this, too, because I still have that little house. Honestly, I do. In that place where I keep the best-loved things in life— friendships, kindnesses, little pleasures, things treasured but never owned—it is strong and safe. A finished task. A search completed. A gift once received.

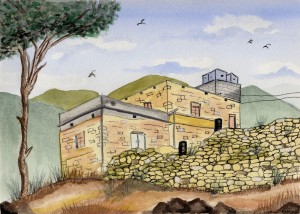

Wayne salvaged a stable, made it comfortable and beautiful. The villagers were amazed when they saw what he had done. The mule who used to live there tried to come home. Our young friends filled it with love and laughter. We cooked hamburgers on the roof and lingered to watch the stars appear. We decorated an artificial Christmas tree and a real wall of sandbags. Snow fell and shrapnel, but we were safe. We stood by a hurting country and did our work. And when I wrote my story, the house was central to the plot and symbolic of things loved and learned, so I put its picture on the cover of the book. I made it famous!

The truth is that whoever demolished that little house made it ours at last. Abandoned, damaged, rejected, revised, borrowed and blessed, sold and resold, devalued and destroyed, it can no longer belong to anyone but those who love it.

Important!

Frances Fuller and her husband Wayne were Southern Baptist missionaries in Lebanon. They are now retired. Their daughter Jan graduated from the same Beirut high school as me, in the same year as me, once upon a time long ago. She is now an Episcopalian priest and an interfaith chaplain at Elon University. It’s been more than 40 years since I’ve seen any of them, but they continue to bless and enrich my life,

— Monsieur d’Nalgar

http://www.inborrowedhouseslebanon.com/?p=338 or http://bit.ly/1KAWx5I

Watercolor painting by Tara Dunn (Said) was a gift to Frances Fuller.

1 comments

This is beautiful and rings of truth for all that we love and hold dear. Thanks for sharing.