Pastors, Not Politicians, Turned Dixie Republican

Pastors, Not Politicians, Turned Dixie Republican

By Chris Ladd, Mar 27, 2017, 09:16am

“White Democrats will desert their party in droves the minute it becomes a black party.”

Kevin Phillips, The Emerging Republican Majority, 1969

Thirty years ago, archconservative Rick Perry was a Democrat and liberal icon Elizabeth Warren was a Republican. Back then there were a few Republican Congressmen and Senators from Southern states, but state and local politics in the South was still dominated by Democrats. By 2014 that had changed entirely as the last of the Deep South states completed their transition from single-party Democratic rule to single party rule under Republicans. The flight of the Dixiecrats was complete.

Reasons for the switch are not so hard to understand. Legend has it that President Johnson, after signing the 1964 Civil Rights Act, mourned “we’ve lost the South for a generation.” That quote might be apocryphal, but it accurately reflects contemporary opinion. Fiery segregationist George Wallace would carry five Southern states in his third party run for President in 1968. Southern anger over the Democratic Party’s embrace of civil rights reforms was no secret and no surprise.

While the “why” behind the flight of the Dixiecrats is obvious, the “how” is more difficult to establish, shrouded in myths and half-truths. Analysts often explain the great exodus of Southern conservatives from the Democratic Party by referencing the Southern Strategy, a cynical campaign ploy supposedly executed by Richard Nixon in his ’68 and ’72 Presidential campaigns, but that explanation falls flat. Though the Southern backlash against the Civil Rights Acts showed up immediately at the top of the ticket, Republicans farther down the ballot gained very little ground in the South between ’68 and ’84. Democrats there occasionally chose Republican candidates for positions in Washington, but they stuck with Democrats for local offices.

Crediting the Nixon campaign with the flight of Southern conservativesfrom the Democratic Party dismisses the role Southerners themselves played in that transformation. In fact, Republicans had very little organizational infrastructure on the ground in the South before 1980, and never quite figured out how to build a persuasive appeal to voters there. Every cynical strategy cooked up in a Washington boardroom withered under local conditions. The flight of the Dixiecrats was ultimately conceived, planned, and executed by Southerners themselves, largely independent of, and sometimes at odds with, existing Republican leadership. It was a move that had less to do with politicos than with pastors.

Southern churches, warped by generations of theological evolution necessary to accommodate slavery and segregation, were all too willing to offer their political assistance to a white nationalist program. Southern religious institutions would lead a wave of political activism that helped keep white nationalism alive inside an increasingly unfriendly national climate. Forget about Goldwater, Nixon or Reagan. No one played as much of a role in turning the South red as the leaders of the Southern Baptist Church.

Jesus and Segregation

There is still today a Southern Baptist Church. More than a century and a half after the Civil War, and decades after the Methodists and Presbyterians reunited with their Yankee neighbors, America’s largest denomination remains defined, right down to the name over the door, by an 1845 split over slavery.

Spirituality may be personal, but organized religion, like race, is a cultural construct. When you’ve lost the ability to mobilize supporters based on race, religion will serve as a capable proxy. What was lost under the banner of “segregation forever” has been tenuously preserved through a continuing “culture war.” A fight for white nationalism and white cultural supremacy has in some ways been more successful after its transformation into an expressly religious, rather than merely racist crusade.

Religion is endlessly pliable. So long as pastors or priests (or in this case, televangelists) are willing to apply their theological creativity to serve political demands, religious institutions can be bent to advance any policy goal. With remarkably little prodding, Christian churches in Germany fanned the flames for Hitler. Liberation theology thrived alongside Communist activism in Latin America. The Southern Baptist Church was organized specifically to protect slavery and white supremacy from the influence of their brethren in the North, a role that has never ceased to distort its identity, beliefs and practices.

In 1956, the Supreme Court had recently struck down school segregation in the Brown v. Board of Education case. President Eisenhower had sponsored sweeping civil rights legislation. Dr. Martin Luther King was organizing bus boycotts in Montgomery. Pressure was building against segregation across the South. At that time, there may have been no more influential figure in the Southern Baptist Convention than W.A. Criswell, the pastor of the enormous First Baptist Church in Dallas.

At a convention in South Carolina, Criswell turned his popular fire and brimstone style on the “blasphemous and unbiblical” agitators who threatened the Southern way of life. Beyond all the boilerplate racist invective, Criswell outlined an eerily prescient rhetorical stance, a framework capable of outlasting Jim Crow. In a passage that managed to avoid explicit racism, he described what would become the primary political weapon of the culture wars:

Don’t force me by law, by statute, by Supreme Court decision…to cross over in those intimate things where I don’t want to go. Let me build my life. Let me have my church. Let me have my school. Let me have my friends. Let me have my home. Let me have my family. And what you give to me, give to every man in America and keep it like our glorious forefathers made – a land of the free and the home of the brave.

Long after the battle over whites’ only bathrooms had been lost, evangelical communities in Houston or Charlotte can continue the war over a “bathroom bill” using a rhetorical structure Criswell and others built. He had constructed a strangely circular, quasi-libertarian argument in which a right to oppress others becomes a fundamental right born of a religious imperative, protected by the First Amendment. Criswell’s bizarre formula, as it metastasized and took hold elsewhere, could allow white nationalists to continue their campaign as a “culture war” long after the battle to protect segregated institutions had been lost.

Southern Baptists remained at the vanguard of the fight to preserve Jim Crow until the fight was lost. A generation later you might hear Southern Baptists mention that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was a Baptist minister. They are less likely to explain that King was not permitted to worship in a Southern Baptist Church. African-American Baptists had their own parallel institutions, a structure that continues today.

Evangelical resistance to the civil rights movement was not uniform, but dissent was rare and muted. Southern Baptist superstar Billy Graham was cautiously sympathetic to King. Early in King’s career, in 1957, Graham once allowed King to lead a prayer from the pulpit in one of his campaigns in faraway New York City. Graham advised King and other civil rights leaders on organizational matters and offered considerable back-channel support to the movement. However, in public Graham was careful to keep a safe distance and avoided the kind of open displays of sympathy for civil rights that might have complicated his career.

King was once invited to speak at a Southern Baptist seminary in Louisville in 1961. Churches responded with a powerful backlash, slashing the seminary’s donations so steeply that it was forced to apologize for the move. Henlee Barnette, the Baptist professor responsible for King’s invitation at the seminary, nearly lost his job and became something of an outcast, a status he would retain until he was finally pressured to retire from teaching in 1977.

In 1965, after President Johnson’s second landmark Civil Rights Act was passed, the Southern Baptists formally abandoned the fight against segregation with a bland statement urging members to obey the law. In 1968, the Southern Baptist Convention formally endorsed desegregation. That same year, in a remarkably passive-aggressive counter to their apparent concession on civil rights, they elected W.A. Criswell to lead the denomination.

Onward, Christian Soldiers

Defeated and demoralized, segregationists in the 1970’s faced a frustrating problem – how to rebuild a white nationalist political program without using the discredited rhetoric of race. Religion would provide them their answer. Armed with the superficially race-neutral rhetorical formula Criswell had described, prominent Southern Baptist ministers like Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson would emerge to take up the fight. All they needed was a spark to light a new wave of political activism.

In 1967, Mississippi began offering tuition grants to white studentsallowing them to attend private segregated schools. A federal court struck down the move two years later, but the tax-exempt status of these private, segregated schools remained a matter of contention for many years. Under that rubric, evangelical churches across the South led an explosion of new private schools, many of them explicitly segregated. Battles over the status of these institutions reached a climax when the Carter Administration in 1978 signaled its intention to press for their desegregation.

It was the status of these schools, a growing source of church recruitment and revenue, that finally stirred the grassroots to action. Televangelist Jerry Falwell would unite with a broader group of politically connected conservatives to form the Moral Majority in 1979. His partner in the effort, Paul Weyrich, made clear that it was the schools issue that launched the organization, an emphasis reflected in chain events across the 1980 Presidential campaign.

The rise of the religious right is usually credited to abortion activism, but few evangelicals cared about the subject in the 70’s. The Southern Baptist Convention expressed support for laws liberalizing abortion access in 1971. Criswell himself expressed support for the Supreme Court’s decision in Roe, taking the traditional theological position that life began at birth, not conception. The denomination did not adopt a firm pro-life stance until 1980.

In August of 1980, Criswell and other Southern Baptist leaders hosted Republican Presidential candidate Ronald Reagan for a rally in Dallas. Reagan in his speech never used the word “abortion,” but he enthusiastically and explicitly supported the ministers’ position on protecting private religious schools. That was what they needed to hear.

Evangelical ministers, previously reluctant to lend their pulpits to political activists, launched a massive wave of activism in Southern pews in support of the Reagan campaign. The new President would not forget their support. Less than a year into his Administration, Reagan officials pressed the IRS to drop its campaign to desegregate private schools.

In a casually triumphant moment in 1981, Reagan advisor Lee Atwater let down his guard, laying bare the racial logic behind the Republican campaigns in the South:

You start out in 1954 by saying, “N…r, n…r, n…r.” By 1968 you can’t say “n…r”—that hurts you, backfires. So you say stuff like, uh, forced busing, states’ rights, and all that stuff, and you’re getting so abstract. Now, you’re talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you’re talking about are totally economic things and a byproduct of them is, blacks get hurt worse than whites.… “We want to cut this,” is much more abstract than even the busing thing, uh, and a hell of a lot more abstract than “N…r, n…r.”

For decades, men like Atwater had been searching for the perfect “abstract” phrasing, a magic political dog whistle that could communicate that “N…r, n…r” message behind a veneer of respectable language. Though quick to take credit for Reagan’s win, the truth was that Atwater and others like him had mostly failed. Their efforts to construct their dog whistle out of taxes and other traditional Republican talking points never quite connected on a deep enough emotional plane to turn the tide at the local level.

It was religious leaders in the South who solved the puzzle on Republicans’ behalf, converting white angst over lost cultural supremacy into a fresh language of piety and “religious liberty.” Southern conservatives discovered that they could preserve white nationalism through a proxy fight for Christian Nationalism. They came to recognize that a weak, largely empty Republican grassroots structure in the South was ripe for takeover and colonization.

Fired by the success of their efforts at the top of the ballot in 1980, newly activated congregations pressed further, launching organized efforts to move their members from pew to precinct, filling the largely empty Republican infrastructure in the South. By the late 80’s religious activists like Stephen Hotze in Houston were beginning to cut out the middleman, going around pastors to recruit political warriors in the pews. Hotze circulated a professionally rendered video in 1990, called “Restoring America,” that included step-by-step instructions for taking control of Republican precinct and county organizations. Religious nationalists began to purge traditional Republicans from the region’s few GOP institutions.

The Southern Strategy was not a successful Republican initiative. It was a delayed reaction by Republican operatives to events they neither precipitated nor fully understood. Republicans did not trigger the flight of the Dixiecrats, they were buried by it.

A young Texas legislator, Rick Perry, spent much of 1988 campaigning for his fellow Southern Democrat, Al Gore. In the crowded landscape of Texas Democratic politics, Perry showed little breakout potential, but he was aware of the activism that was sweeping Democratic Southern conservatives into empty Republican precincts all over the state. The next year Perry made a bold move, switching to the GOP and rising immediately to the front ranks as a potential statewide candidate.

It was in the 90’s, not the 70’s, that Southern conservatives at the local level finally took flight into the GOP. Armed with the strange, apparently race-neutral logic Reverend Criswell had laid out in the fight for Jim Crow, and organized by a new generation of religious leaders, an enormous wave of party-switching transformed grassroots politics in the South. Republicans seized control of the Texas state legislature in 2002 for the first time ever apart from Reconstruction. When Republicans took control of the Arkansas legislature in 2014, the flight of the Dixiecrats was over and Republicans controlled state government across all of the former Confederacy.

The Past Is Never Dead

Russell Moore became the President of the Southern Baptist Convention’s social outreach arm in 2013. In that capacity, he began to challenge many of the darker elements of the church’s history. From a post in the church traditionally dedicated to hand-wringing over gay rights and dirty movies, Moore criticized those who stirred up hatred against refugees and ignored matters of racial justice. He drew sharp criticism when he denounced the Confederate Flag, explaining, “The cross and the Confederate flag cannot co-exist without one setting the other on fire.”

The real fury came when Moore applied to Donald Trump the same standard of conduct Baptists had demanded of Bill Clinton. Southern Baptist leaders in the 90’s savaged President Clinton as the details of the Lewinski Affair began to surface. Moore drew the obvious comparison last year between Trump and Bill Clinton, urging voters to reject the 2016 Republican nominee. As religious leaders lined up solidly behind Trump last fall, Moore commented, “The religious right turns out to be the people the religious right warned us about.”

In the end, evangelical voters backed Donald Trump by a steeper marginthan their support for Romney in ‘12.

Today, W.A. Criswell’s Dallas megachurch is pastored by Robert Jeffress, who has remained faithful to the most bigoted strains of the olde tyme religion. He has led an effort to withdraw funding for Russell Moore’s organization. Jeffress has called the Catholic Church “a Babylonian mystery religion.” He explained that Obama was sent to pave the way for the Antichrist. He has demogogued relentlessly on gay marriage. And naturally, he endorsed Donald Trump.

Billy Graham’s son, Franklin, retooled the ministry he inherited, turning it into something a civil rights era segregationist could love without reservation. Graham, who earns more than $800,000 a year as the head of his inherited charity, has made anti-Muslim rhetoric a centerpiece of his public profile and ministry. While his father quietly befriended Martin Luther King, the younger Graham has chosen a different path. In response to the Black Lives Matter movement, Graham explained that black people can solve the problem of police violence if they teach their children “respect for authority and obedience.” Franklin Graham enthusiastically supports Donald Trump.

Jerry Falwell’s son also inherited the family business, serving now as president of his father’s university. His support for Trump is less surprising than Graham’s, and far less of a departure from his father’s work. Falwell spoke in support of Trump at the Republican National Convention.

Russell Moore may envision an evangelical movement unhindered by racism and bigotry, but just like Henlee Barnette, the Baptist professor who invited King to speak at a Southern Baptist seminary, Moore is wrestling with a powerful heritage. For Jeffress, the heir to W.A. Criswell’s pulpit, to champion an effort to silence Moore, reflects the powerful persistence of an unacknowledged past. After being pressed into an apology for his “unnecessarily harsh” criticisms, Moore has been allowed to keep his job – for now.

Public perception that a “Southern strategy” conceived and initiated by clever Republicans turned the South red is worse than false. By deflecting responsibility onto some shadowy “other” it blocks us from reckoning with the past or changing our future. History is a powerful tide, especially when it runs unseen and concealed. A refusal to honestly confront our past leaves us to repeat our mistakes over and over again.

Texas House member Rick Perry was taking a chance in 1989, when he decided to leave the Democratic Party to become a Republican. He leaned heavily on the emerging religious right and their campaign to convert the state’s Democratic majority. His efforts were richly rewarded. Baptist mega-pastor Robert Jeffress was a major supporter along with other evangelical leaders. Now Perry, after becoming the longest-serving governor in Texas history, sits in Donald Trump’s cabinet as the Secretary of Energy.

No one needs to say “N..r, n..r” anymore. With help from evangelical pastors, this new generation of politicians has found a new political party and a fresh language with which to stir old grievances and feed their power. By merely refining their rhetoric and activating evangelical congregations, a new generation of Southern conservatives grow ever closer to winning a fight their forebears once thought was lost.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/chrisladd/2017/03/27/pastors-not-politicians-turned-dixie-republican/

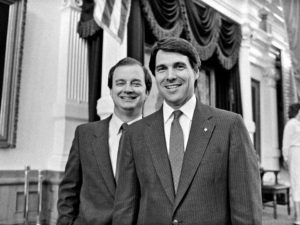

Photograph of Rick Perry and John Sharp serving together as Democrats in the Texas Legislature in 1987 (Texas State Library and Archives Commission).