Why Muslim Voters Love Bernie Sanders

By Steve Friess, 2/26/20 at 10:53 AM EST

At last night’s messy Democratic debate in Charleston, South Carolina, one of the messiest moments came when Bernie Sanders was asked to address the concerns of American Jews over his Mideast policies. The Vermont senator firmly voiced his commitment to protect the independence and security of Israel. But he also called Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu “a reactionary racist” and coupled his support for Israel with the view that “you cannot ignore the suffering of the Palestinian people.”

The response from the candidate, who increasingly looks like the frontrunner in the Democratic race, will likely serve to solidify feelings about Sanders among two key constituencies: Muslim voters, who strongly support him, and Jewish voters, who do not—even though he may be the first Jewish person to become the presidential nominee of a major political party in the U.S.

In fact, in a national poll of Muslim Democrats released by the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) just before primary season got underway Sanders was the clear leader, with 39 percent support to Joe Biden’s 27 percent. The rest of the Democratic contenders were all in single digits. And in the weeks since, that support has only seemed to grow stronger.

For many Americans, everything about this development defies well-worn stereotypes about Muslims—that they’re instinctively hostile to or suspicious of Jews and that the dogma of their faith demands they be extreme social conservatives who would find a stridently pro-choice, pro-LGBTQ candidate unacceptable. But Sanders, in fact, has a long history of outreach to Muslim Americans that is serving him well in the current race. Says Medicare For All activist Abdul El-Sayed, “Bernie is the one candidate who has made the effort to engage our community and speak to us where we are.”

Early Signs of Strength

The strong support for Sanders among Muslim voters was abundantly clear in Iowa, during a caucus otherwise marred by confusion and suspicion about the outcome.

On caucus night on February 3 at the Muslim Community Organization mosque in Des Moines, for instance, voting didn’t even go to a second round. When Democrats there were first told to head to their candidates’ corners, just two people each dispersed to show support for Andrew Yang and Elizabeth Warren and one went for Pete Buttigieg. The rest, another 115 folks, congregated for Bernie Sanders.

Similarly lopsided breakdowns in Sanders’ favor emerged at other mosques that served as caucus sites. What’s more, the only reason there were caucuses in mosques at all—the first time for a presidential primary caucus anywhere in the U.S.—was because the Sanders campaign lobbied the state Democratic Party to do so to encourage Muslim participation.

Six days after the Iowa caucus, on a conference call of more than 100 “Muslims For Bernie” volunteers, some speakers even referred to him as Ammu Bernie, using the Arabic for “uncle,” so familiarly and affectionately do they regard the independent senator from Vermont.

Yet another vote of confidence: Ten days before Super Tuesday, when voters from 14 states will head to the polls—including California and Texas, which have the largest number of voting-age Muslims—Emgage, the nation’s biggest Muslim PAC, endorsed Sanders, saying the candidate “has built a historically inclusive and forward-thinking movement.”

Courting the Muslim Vote

That the majority of Muslim voters would pick a Democrat has become a given in recent years. More than 74 percent of Muslim voters backed Democrats in exit polling from the 2012, 2016 and 2018 elections, CAIR says—a significant shift since the 2000 election, when Republican George W. Bush took 42 percent of the Muslim vote, according to a 2001 Zogby survey.

After the 9/11 terror attacks, Bush’s “War on Terror” and its harsh rhetoric against what it called Islamic extremism, Muslim Americans migrated in droves to the Democratic Party. “That’s when you start seeing Republican candidates run on really anti-Muslim platforms and engaging in very Islamophobic campaign rhetoric,” says Robert McCaw, CAIR’s director of government affairs director.

As Muslims became a consistent Democratic voting bloc—one with substantial numbers not only in California and Texas but also in fellow Super Tuesday states Minnesota and Virginia, as well as Michigan, which votes a week later—Sanders has been singular in his direct, aggressive effort to win their support.

To be sure, he’s not the only Democratic candidate to reach out to Muslim voters. Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren in January held a one-hour conference call with Muslim leaders to hear their concerns and vie for their help in her quest for the Democratic nomination. And former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg earlier this month sent an Arab-American campaign surrogate to hold two meetings with community leaders in Michigan and has taken out Arabic-language ads in the Dearborn-based Arab American News in advance of that state’s primary on March 10.

But Sanders is the only one of the major 2020 presidential contenders who has visited mosques or appeared publicly with prominent Muslim elected leaders from the Democratic Party such as Representatives Ilhan Omar of Minnesota and Rashida Tlaib of Michigan. Meanwhile, Bloomberg’s Arabic ads, instead of boosting him within the community, conjured up controversy in the Detroit media with many Muslim leaders saying the outreach was disingenuous given his past support of undercover surveillance of New York City mosques while he was mayor.

Sanders, on the other hand, is seen as the real deal. He has a career-long history of outreach to Muslims; it’s not something that began with the 2020 campaign or even his run for president in 2016. Along the way, he’s also forged alliances with some purported anti-Semitic figures and has been a longstanding critic of Israel’s treatment of Palestinians—factors that may help explain why he polls poorly among Jewish voters.

“Jewish reticence for Sanders has a number of sources,” wrote columnist Alex Zeldin last week for The Forward, a Jewish magazine, under the headline “Bernie Sanders says he’s proud to be Jewish. Will Jewish voters care?” “Some may worry that any prominent Jew in the race could attract anti-Semitism. Others may feel alienated by Sanders’ online fans, many of whom have a reputation for harassing his critics. Then there are his surrogates, which include Linda Sarsour, who repeatedly antagonized American Jews, including with attempts to make Jews choose between Zionism and feminism, and by hosting a conference in which Sarsour sought to define and explain anti-Semitism to Jews.”

Sanders also hasn’t worked particularly hard to court this demographic. The day after his resounding Nevada caucus win put him in the driver’s seat for the Democratic nomination, he infuriated many in the Jewish political world by tweeting that he wouldn’t attend the American Israel Public Affairs Committee convention in Washington D.C. in early March because he was “concerned about the platform AIPAC provides for leaders who express bigotry and oppose basic Palestinian rights.”

An “Authentic” Voice

All this just makes Sanders’ views seem more authentic to Arab-American voters, according to Sanders’ campaign manager, Faiz Shakir, the 40-year-old Muslim son of Pakistani immigrants.

“You get tarred as somehow a member of a terrorist group, told you are somehow not fully American because your allegiances may not be to the U.S. Constitution, you get all kinds of Islamophobia spewed against you,” Shakir says. “Then here comes Bernie Sanders who stands up and says, ‘I’m going to a Muslim convention’ and he speaks authentically about Kashmir, the Israel-Palestinian dispute, the Afghanistan war, the Chinese treatment of the Uyghurs. Muslims have been dealt injustices from American politicians of both parties and then Bernie Sanders says, ‘I see that, I speak to it and I tell you I’ll do better.’ ”

El-Sayed, the Medicare for All activist whom Sanders endorsed in his failed pursuit of the 2018 Democratic nomination in Michigan’s gubernatorial race, agreed: “National Democrats all talk about us when it scores some political points for them, like when they want to virtue-signal that they’re standing with Muslims [against Trump’s ban on travel from Muslim-majority nations] and fighting for our rights. But they don’t do the work of actually engaging the issues as we see them or engaging on our turf. Bernie is the one candidate who has made the effort to engage our community and speak to us where we are.”

Shakir and CAIR’s McCaw both trace the origins of Muslim affinity for Sanders at least back to his 2003 vote against the authorization of force that started the Iraq War. In 2007, as Keith Ellison of Minnesota was about to become the nation’s first Muslim member of Congress and controversy swirled in right-wing media over his plan to be sworn in on the Quran, Sanders was the first to call to bolster his resolve.

“Brother Bernie, he said, ‘You swear on anything you want,’ ” says Ellison, now Minnesota attorney general, on that Muslims for Bernie call. “That’s why I love Bernie.” More recently, Sanders campaigned for Tlaib, Omar, El-Sayed and other Muslim candidates in 2018—and they’ve all endorsed him this year in return.

“Bernie Sanders offers an authentic message that has stood the test of time,” McCaw says. “Also, it’s not just that he speaks to Muslim issues. He embraces Muslims speaking for his campaign in a way that I have not seen another candidate do.”

An Agenda That Works

Sanders’ appeal goes beyond his outspoken opposition to bigotry against Muslims and U.S. interference in the affairs of Muslim-majority countries. A 2016 exit poll by CAIR found Muslims rated civil rights, education and the economy as issues of even greater concern than opposition to Trump’s proposed Muslim ban or the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. So the rest of Sanders’ creed—his drive for universal health care and free college and against income inequality, gun violence and climate change—resonates because the vast majority of Muslims in the U.S. are also minorities living in urban areas, says Youssef Chouhoud, a political science professor at Christopher Newport University in Newport News, Virginia.

“A large percentage of American Muslims are actually at or below the poverty line, so these economic policies appeal to them as well,” Chouhoud says. “They gravitate toward Bernie for that broader platform, first and foremost. And then it just so happened that he has a foreign policy that they find appealing as well.”

McCaw echoed this, noting that Muslims are “the most ethnically diverse religious community in the United States. We probably have one of the highest rates of interracial marriage in America. Our issues are a combination of almost every minority community’s issues, all unified around the issues of progressive social justice.”

Still, the idea that Muslim Americans want a Jew as their standard-bearer is intriguing. Prominent Palestinian-American activist Linda Sarsour, a Sanders surrogate, winks at that twist when she marvels over the fact that she “fell in love with an old Jewish guy,” a routine laugh line in her speeches.

And far from Sanders avoiding discussion of his faith around Muslim groups, he uses his family’s immigrant experience to relate to their experiences as targets of oppression and bigotry. At the Islamic Society of North America convention in July 2019, for instance, he opened by declaring himself the “proud son of Jewish immigrants,” a phrase the elicited applause. The Holocaust, he told the crowd, taught him “how important it is for all of us to speak out forcefully wherever we see prejudice and discrimination.”

Sometimes his authenticity does risk alienating Muslims, but audiences give him props for his consistency. “I am a strong supporter of the right of Israel to exist in independence, peace and security,” he said later in that speech. “But I also believe that the United States needs to engage in an even-handed approach towards that long-standing conflict which results in ending the Israeli occupation and enabling the Palestinian people to have independence and self-determination in a sovereign, independent, economically viable state of their own.”

Shakir conceded that some more socially conservative Muslims struggle with Sanders’ stances on LGBTQ equality, abortion and legalized marijuana. But “people end up saying, ‘Hey you know I don’t agree with Bernie Sanders on this or that, but I know he really believes it and so I appreciate that,’ ” Shakir says. “What brings it all together is that he’s trustworthy, he’s compassionate, he has the qualities that I feel comfortable with as a leader.”

Sanders surrogate Amer Zahr, a comic-activist who in November hosted an Arab Americans For Bernie organizing meeting in Dearborn bristles at the idea that disagreement on this topic or Sanders’ Jewish identity could be a deal-breaker. “Yes, the Palestinian-Israeli thing is out there and that creates a lot of tension from time to time, but that doesn’t automatically color the way we see every Jewish person because we have been living peacefully with Jewish people and Christian people for centuries and centuries and centuries,” Zahr says. “The notion that we are automatically suspicious of Jewish people, it’s just simply not the case. We actually view Bernie’s Jewishness as a positive, something that connected us more with him as being minorities in this country.”

Backlash From Jewish Voters?

In fact, Sanders’ embrace of Muslim voters generally and some Muslim leaders in particular may cost him politically—with Jewish voters. A Pew Research survey released in January showed he drew support of just 11 percent of Democratic Jewish voters—the lowest he drew with any religious group—versus 31 percent for Joe Biden and 20 percent for Elizabeth Warren. That 11 percent figure is stubborn and hasn’t grown, even as his overall polling averages have; he got the same percentage of Jewish support in a May 2019 poll too.

Overall, there has been precious little fanfare in the Jewish media over the increasing likelihood that he could be the first Jewish person to become a major political party’s presidential candidate or his unprecedented wins in the early voting. Sanders is not only the first Jewish politician to win the first three contests, but he’s the first candidate to do so, period, from either party.

Specifically of concern to many Jewish pundits and leaders is Sanders’ close relationship with Sarsour, whose strident anti-Israel comments, they believe, occasionally take on an anti-Semitic hue. In December, for instance, Sarsour asked in a speech to the American Muslims for Palestine conference in Chicago how anyone could claim to be against white supremacy but support “a state like Israel that is based on supremacy, that is built on the idea that Jews are supreme to everyone else.”

Sanders, who opposes the Sarsour-led boycott, divest and sanction (BDS) movement to economically punish Israel for its Palestinian policies, nonetheless did not disavow Sarsour’s remarks. That earned him yet another round of opprobrium from Jewish leaders like Rabbi Jacob Herber of Wisconsin, who tweeted in response to Sanders’ silence on Sarsour, “I abhor Donald Trump for the same reasons you do. But I’ll be damned if I’m going to vote for Bernie Sanders.”

For his part, Sanders has put more effort into courting Jews than he did in 2016, when he was criticized for rarely, if ever, discussing his religion. In an essay last year for Jewish Currents, he wrote: “It is true that some criticism of Israel can cross the line into anti-Semitism, especially when it denies the right of self-determination to Jews, or when it plays into conspiracy theories about outsized Jewish power. I will always call out anti-Semitism when I see it.”

At a hall in Derry, New Hampshire, shortly before that state’s primary, Sanders explained that his drive for social justice began when, as a young Jewish boy in Brooklyn, he learned about the Holocaust—an answer that earned him unusual plaudits from the Jewish media.

Yet if Sanders’ outreach to the Muslim community loses him some support among Jewish voters, it has paid political dividends too. The effort can easily be regarded as decisive in his poll-defying, surprise 10,000-vote win over Hillary Clinton in the 2016 primary in Michigan, which has one of the largest concentration of Arabs and Muslims in the U.S. Now the advantage may help him run up the score when Democrats in the Wolverine State vote on March 10.

“He’s going to win the state of Michigan by a bigger majority than he did last time,” El-Sayed says. “His campaign is going to be able to pick up a lot of momentum that was started by his campaign in 2016.”

Even before Michigan, the Sanders cause will likely be helped by the large numbers of Muslim and Arab voters in key Super Tuesday contests. “It’s not that the Muslim community will swing the election in any state, but we’re definitely in a position to tip it,” Shakir says. “If you can increase participation rates by just a few percentage points, you can actually have a major impact.”

In fact, according to a study by Emgage, voter turnout among Muslim Americans for the 2018 midterm elections in the key states of Florida, Michigan, Ohio and Virginia—all four with primaries in early to mid-March—was 25 percentage points higher than in 2014, compared with a 14 percent jump in participation among the general electorate in those areas. If any of these contests are as close as, say, the Iowa caucus turned out to be, says Shakir, “it demonstrates that any increase can be everything.”

Steve Friess is a Newsweek contributor based in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Follow him on Twitter at @SteveFriess.

https://www.newsweek.com/why-muslim-voters-love-bernie-sanders-1489226

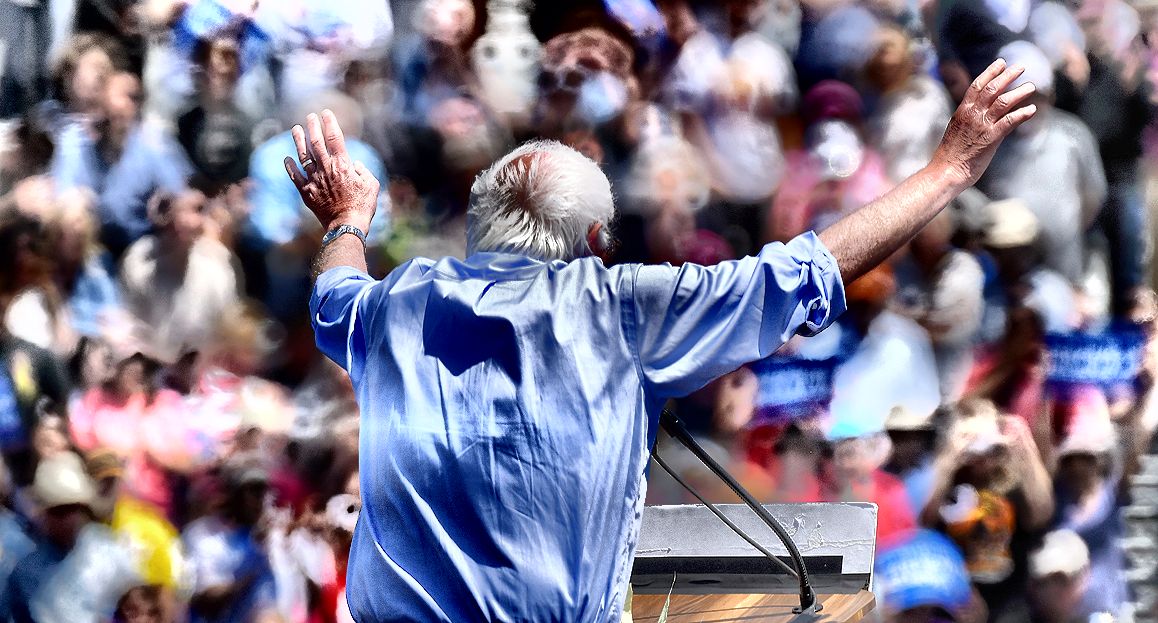

Photograph (modified) of Bernie Sanders by Getty. http://www.politico.com/story/2016/06/bernie-sanders-california-223925