1950s U.S. Foreign Policy Looms Large in Lebanon

1950s U.S. Foreign Policy Looms Large in Lebanon

By Jacob Boswell, July 29, 2022

The Cold War may be over, but the legacy of containment looms large over Lebanon. For decades, the U.S. has been the single largest financial supporter of the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF), in a bid to balance Iran’s influence in the economically and politically stricken country. Despite growing U.S. isolationism, the Biden administration shows no sign of reversing this time-honored interest in Lebanese security, confirming $67 million in aid to the armed forces earlier this year.

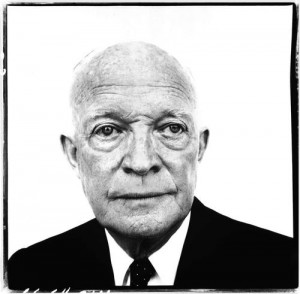

Reducing Lebanon to a theater of containment seems to come naturally to policymakers in Washington. In fact, the mindset can be traced back to the Eisenhower Doctrine — a short-lived U.S. pledge to contain communism in the Middle East — which dragged the U.S. into its first conflict in the Arab region.

At the height of the Cold War, the U.S. first became embroiled in Lebanon’s tricky domestic politics when it sent Marines to storm a beach near Beirut, in the name of fighting international communism. Unfortunately, the White House’s meddling hand only complicated the country’s constitutional crisis and set a dangerous course for U.S. involvement in the Middle East. In the early 2000s, the Bush administration made a similar mistake, projecting a new international conflict — this time, the global war on terror — onto the troubled nation. In both crises, Washington’s reductive containment mentality only deepened complex internal fissures within Lebanon’s society and achieved little for its people.

Roughly 60 years before the United States gave its blessing to Lebanon’s October 2019 Revolution, it was busy stamping out another popular anti-government movement in the land of the cedars. In 1958, civil war gripped Lebanon. Muslims sympathetic to pan-Arabism, a new political force aiming to drive out Western imperial powers, hoped to unseat Camille Chamoun, Washington’s corrupt lackey who served as Lebanon’s second president. When Chamoun requested support through the Eisenhower Doctrine, America was dragged into its first combat operation in the region.

On July 15, 1958, 1,700 U.S. Marines stormed a stretch of Lebanon’s then-pristine coastline in an operation codenamed Blue Bat. In the Mediterranean, 70 warships and three aircraft carriers stood by to provide naval and air support, while another air division back in the U.S. was primed for action. Soon the Marines, expecting to face ferocious pan-Arab militiamen, instead met up with curious mobs of bikini-clad sunbathers, bemused teenagers and opportunistic street peddlers.

The following months proved to be no less farcical; throughout the crisis, the U.S. never stationed more than 14,000 troops in Lebanon. By Oct. 25, they had all departed, leaving the country in relative stability and U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower with the justifiable claim that he had “waged peace.”

By hitting the panic button, Chamoun unwittingly began a new era of U.S. involvement in the Middle East. Operation Blue Bat may have been a stroll along the beach for the Marines who landed at Khalde, but the invasion was both immensely risky in the short run and immeasurably costly in the long run.

At the time, many celebrated Blue Bat for having achieved a hat trick of foreign policy goals: strengthening pro-Western regimes in both Lebanon and Jordan, consolidating America’s special relationship with the United Kingdom, which was growing nervous after the spectacular loss of influence in Iraq and Egypt, and securing the steady flow of oil from the Persian Gulf into Europe. Moreover, the intervention was relatively cheap (costing $200 million), swift and bloodless; only one American service member died from rogue sniper fire, while not a single Lebanese combatant or civilian sustained injury.

So much for “Pandora’s Box,” which had terrified both Eisenhower and British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan on the eve of the landing. In the build-up to Operation Blue Bat, Western powers outwardly expressed fear that Lebanon was in danger of caving to Soviet influence through the vehicle of Arab nationalism. Beginning with the July 23 Revolution in 1952, Egypt’s charismatic leader and former U.S. ally, Gamal Abdel Nasser, had unleashed a powerful new force in the form of pan-Arab nationalism. Always delivered with punchy oratory, Nasser’s vision was clear: Western imperialism has failed, and now Arabs must unite under a greater Arab project.

Nasser’s popularity soared further after the Suez Crisis in 1956, during which he emerged victorious against superior military forces, evicted the British from Egypt, and effectively embarrassed a British prime minister into resignation. In early 1958, Egypt and Syria joined to form the United Arab Republic (UAR), confirming U.S. fears that Nasserism threatened U.S. and European interests beyond Egypt. To make matters worse, the Egyptian strongman appeared to be moving closer to the Soviets, recognizing the People’s Republic of China, and signing a multimillion-dollar arms deal with Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic and Slovakia), a Soviet satellite state.

By the late ‘50s, these conflicting regional currents were creating deep rifts in Lebanese society. Many Sunni Muslims sympathized with Nasser and his calls for Arab solidarity, while Christians tended to identify with Western powers, especially the pro-U.S. Chamoun — a deeply unpopular Christian president whom the U.S. had helped cling to power during the turbulent years of 1957 and 1958. Adding to allegations of corruption and election fraud, Chamoun also appeared poised to remain in office for another six-year term, contrary to the Lebanese Constitution. Chamoun brutally quashed the protests caused by the resulting constitutional crisis, killing several Nasserite protesters. A small civil war began in which Christian, pro-Chamoun militias battled Nasser-inspired Sunni and Shiite fighters.

The embattled Chamoun sought U.S. support within the framework of the Eisenhower Doctrine — a U.S. pledge to provide economic or military aid to counter any “overt armed aggression from any nation controlled by international communism.” But it was only when a violent coup overthrew the British-backed Hashemite monarchy in Iraq on July 14, 1958, that the situation became urgent. The U.S. was forced into making an unpalatable decision: prop up a friendly but unpopular ruler or undermine the Eisenhower Doctrine. With Nasser’s victory over the Suez still fresh, Eisenhower opted for the former.

The only problem was that the Eisenhower Doctrine was never fit for its purported purpose. The doctrine, Washington claimed, aimed to prevent the spread of communism by isolating Nasser and building a coalition of pro-American, anti-communist, Arab states. However, this logic only held as long as Nasser became a Soviet puppet. In the event, Egypt and Arab nationalism in general proved remarkably resistant to the Cold War dichotomy, undermining the doctrine’s central tenet.

Why Eisenhower and his advisers never even considered that Nasser might live up to his aspiration of “positive neutrality” — in which Egypt sought to remain officially neutral, while benefiting from trade with both Cold War blocs — is the subject of academic debate. One convincing theory, proposed by U.S. diplomatic historian Douglas Little, points to the role of cultural and Orientalist stereotypes in conditioning U.S. policymakers to dismiss Nasser’s ability to remain neutral. This tendency, Little argues, can be traced back to the Versailles Treaty that ended World War I. U.S. President Woodrow Wilson himself, the main architect of self-determination, was reluctant to apply the principle to the Arabs; putting such ideas in the minds of certain “races,” Wilson’s Secretary of State Robert Lansing grumbled in 1918, “is simply loaded with dynamite.”

The Eisenhower Doctrine was flawed in two other important aspects: overestimating America’s political strength in the region and assuming that Arab leaders would play along with the policy. In reality, few Arab leaders rallied to Eisenhower’s anti-communist call for the simple reason that it was politically unpopular to openly side with a Western power. Only Western-aligned Lebanon and Hashemite Iraq officially endorsed the doctrine, and even then, they both demanded concessions in return for the endorsement.

When historians cite the 1958 crisis in Lebanon as Eisenhower’s finest hour, they mainly refer to the brilliant U.S. diplomacy that averted a military disaster after the July 15 landing. It is true that the U.S. ambassador to Lebanon Robert McClintock and State Department representative Robert Murphy put their heads together with the Lebanese army commander Gen. Fouad Chehab and contrived to pretend that the Marines were guests of the Lebanese army. This ruse certainly helped to diffuse the immediate tension and avoided embroiling the U.S. in the civil war. Without the pretense that the Marines were not invaders but Chehab’s guests, the anti-Chamoun militias would have no doubt reacted much more violently, making escalation more likely.

But closer scrutiny shows that the 1958 crisis in Lebanon was not quite as low risk as these tales of level-headed diplomacy suggest. First, the success of Operation Blue Bat owes as much to good luck as to good diplomacy or crisis management. Direct confrontation between U.S. Marines and the anti-Chamoun United National Front was narrowly avoided, as vividly depicted in Brookings director Bruce Riedel’s recent book, “Beirut 1958.”

Favorable regional developments are due some credit for the peaceful outcome of the Lebanese crisis. The July 14 coup extinguished Iraq’s Hashemite monarchy, a regime loyal to the West, and brought to power the anti-imperial Abd al-Karim Qasim. In this climate of uncertainty, Britain and the U.S. feared that

Nasserite sentiment sparked by the Iraqi coup would spill over into neighboring Kuwait and Jordan. Fortunately for the Western powers, the conservative monarchies stood strong. Macmillan did not insist on U.S. military aid in Jordan, settling instead for U.S. “logistic support.” In Kuwait, the pro-British Sabah clan was maintained with minimal effort from the British. Help came from within Lebanon, too, in the form of the earnest efforts of local negotiators. If not for their efforts, combined with several strokes of luck elsewhere in the region, it is unlikely that the crisis would have enjoyed such a bloodless resolution.

Perhaps more concerning are the long-term costs of the 1958 crisis in Lebanon — a legacy that had a lasting impact on the Cold War world of the late 1950s and U.S. policy in the Middle East. In his public statement following Operation Blue Bat, Eisenhower justified the military landing by referring to civil strife “actively fomented by Soviet and Cairo broadcasts,” while making no mention of protecting Israel, protecting Western commercial interests, countering Nasserism, Arab nationalism or even nonaligned nationalism among less developed countries.

These omissions were calculated. By focusing on Soviet aggression, Eisenhower was able to shoehorn the intervention into the Eisenhower Doctrine, viewing the situation in Lebanon through the prism of Cold War ideology. Despite couching Operation Blue Bat in the rhetoric of anti-communism and collective security, Eisenhower privately admitted that Arab nationalism, and not communism, was the real threat to Lebanon in 1958. Communist subversion was nowhere in sight. In a conversation with Macmillan, Eisenhower described the deceit involved in the operation as leaving a “nasty aftertaste.”

The price of maintaining credibility on the world stage was significant. Once they had been made, it was impossible to repudiate military commitments made both through the Eisenhower Doctrine and personal channels with local leaders such as Chamoun and Charles Malik, Lebanon’s ambassador to the U.S. The same notion of credibility was one factor in Lyndon B. Johnson’s decision to plunge the U.S. into the quagmire of Vietnam just six years later, with far more serious consequences.

Another worrying legacy, perhaps more pertinent today, is Eisenhower’s ability to mislead both Congress and the American public about matters concerning the Middle East. Much like subsequent attempts to shape Lebanon, Eisenhower’s policy grossly simplified and misrepresented what was and still is a complex confessional system. Without squeezing the Lebanon crisis to fit the Eisenhower Doctrine — a blueprint of grand international conflict with little relevance to Lebanon — Ike could have never received support for Operation Blue Bat from Capitol Hill. Even at the time, the tactic raised eyebrows. One senator described the whole affair as a “curious outgrowth of the Eisenhower Doctrine.” No other U.S. military foray into an Arab state has ended so peacefully, least of all in Lebanon. The next U.S. combat operation into the country was equally misguided. Washington’s tactics during the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990) involved indiscriminately shelling the tiny country from warships stationed in the Mediterranean and ended in tragedy when 241 U.S. troops were killed in the 1983 barracks bombings.

Since the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990, the Middle East has become a hotspot for U.S. combat operations, costing the lives of thousands of soldiers and hundreds of thousands of civilians. It is an interesting proposition that Operation Blue Bat’s relative success vindicated later U.S. involvement in the region and perhaps even made subsequent administrations complacent when dabbling in the affairs of Arab states, especially Lebanon, where the legacy of containment is even more pronounced.

There are unsettling similarities between Eisenhower’s handling of the 1958 crisis and President George W. Bush’s approach to Hezbollah in the years leading up to the 2006 war with Israel. In both instances, the U.S. endowed essentially domestic Lebanese crises with international meaning. Bush’s insistence on lumping Hezbollah alongside al Qaeda in the global war on terror gave international dimensions to disarming the resistance group, as articulated in United Nations Security Resolution 1559. Between 2003 and 2006, the U.S. took an increasingly active role in containing Iranian and Syrian influence in Lebanon, including by allowing the U.N. Security Council to interpret Lebanon’s constitutional provisions in the investigation into the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri and attempting to delegitimize Syria-aligned President Emile Lahoud.

Like in 1958, U.S. interference at a time of deep and potentially violent constitutional and political crisis was incendiary. Hezbollah’s victory over Israel in the 2006 war shifted the internationalized discourse about the group’s weapons into Lebanon’s own constitutional institutions. Debates about the legitimacy of armed resistance and its relationship with the national armed forces took on unprecedented dimensions, leading to the collapse of the national unity government in November 2007 and sparking a constitutional crisis resembling that of 1958. Like Chamoun, U.S.-backed Prime Minister Fouad Siniora — who steered Lebanon in the wake of Hariri’s assassination — was recognized by the West but denied legitimacy by the domestic opposition. Indeed, this time, U.S. policy did more to fan the flames of sectarian conflict, as Hezbollah supporters clashed with government-aligned militias throughout 2008, largely over the issue of the group’s weapons.

Ironically enough, both crises concluded with an entrenchment of the status quo — a likely outcome even without U.S. interference. In 1958, Chamoun was replaced by Chehab as president, a solution advocated by Nasser himself. In 2008, the Doha Accords reaffirmed Hezbollah’s ability to coexist with the LAF — a model that has been followed ever since and almost certainly not what Washington had in mind in 2003.

With the long view of history, America made several costly decisions during the crisis in 1958. How else might a president have handled such a tense situation? One simple improvement would have been to act with greater transparency. The most plausible explanation for Eisenhower’s decision to stretch the Eisenhower Doctrine to breaking point is that he feared defeat in seeking congressional approval to deploy troops.

But Eisenhower might have drawn less criticism in the Senate had he admitted from the beginning the real reasons for Operation Blue Bat: the concern that Nasser’s Arab nationalism was undermining the West’s security and economic interests in the Middle East. Beirut, after all, was a logistical and financial hub serving all U.S.-aligned conservative regimes in the region. Just two years before the invasion, a new banking secrecy law gave a further boost to the capital’s reputation as a free-wheeling business hub, making it an even more convenient place to stash cash. The U.S. feared that losing sway over Lebanon would damage its commercial interests and access to hydrocarbons in other friendly regimes, including oil-producing Kuwait.

Eisenhower should have been doubly aware of the possibility that the Soviets did not threaten Lebanon after the Syrian crisis of 1957, in which the CIA wrongly concluded that the Damascus government had turned to the USSR. Such transparency from the beginning might also have laid the groundwork for a more nuanced approach to foreign policy in the Middle East, in which complex situations are not reduced to easy binaries: capitalist versus communist, moderate versus radical, terrorism versus security, nuclear weapons versus no nuclear weapons.

The speed with which the U.S. resorted to troops represents another missed opportunity. The landing at Khalde was a knee-jerk reaction to panicked calls from Christian leaders fearing Soviet encroachment. Washington and London acted respectively in Lebanon and Jordan on the belief that Qasim’s coup was Nasserite, and therefore vulnerable to Soviet expansionist designs. Photos of protesters holding posters of Nasser during the coup only confirmed this suspicion; within a day of Qasim seizing power in Baghdad, the Marines landed in Lebanon. However, it later became clear that Qasim had no intention of turning to Nasser for regional leadership, much less to the USSR.

While it is true that Qasim had reached an understanding with the Iraqi Communist Party, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s attempts to court the Iraqis were ultimately frustrated. By early 1959, Nasserism had emerged not as an avenue of, but rather a barrier to Soviet penetration in the Middle East. In this sense, the Iraqi coup — the event that triggered Chamoun’s invocation of the Eisenhower Doctrine — did not greatly alter the regional balance of power between the two great superpowers.

Had Eisenhower taken more time to analyze the coup in Baghdad, drawing on British intelligence already stationed in the country, Qasim’s lack of regional alignment might have emerged yet more quickly. With the knowledge that an invasion by the UAR was not imminent, McClintock would have been able to engineer the peaceful transfer of power to Chehab without the complicating intrusion of U.S. troops. Indeed, there is evidence to suggest that without the Marine landing, the Lebanese could have reached an agreement over who succeeded Chamoun more quickly among themselves. Many local leaders saw Chehab as the natural successor to Chamoun, a fact not wasted on Nasser himself, who favored the transition of power to Chehab.

The crucial error of the U.S. in 1958 was in framing the Lebanese crisis as a clash between the U.S. and the USSR. Washington would do well remembering that lesson in its policymaking today. By continuing its Cold War mentality against Iran, Washington is in danger of simplifying Lebanon to a proxy battleground and misunderstanding Hezbollah as a mere Iranian foreign policy pawn, not as a domestic political and security player in its own right. Continuing this outdated mindset in Lebanon is even more baffling, considering that many analysts regard Iranian containment as a failed policy in Lebanon and the region at large.

Rather than depicting Lebanon as a weak state, whose weakness drags it into repeated external conflict, Washington should acknowledge that Lebanon’s plural form of governance resists binary U.S. understanding of security and sovereignty. Rather, Lebanon’s form of hybrid security remains relatively effective precisely because of its unique consensus of rival political forces and sectarian communities. The U.S. might be better off reallocating funds away from the LAF and into infrastructure projects that serve the Lebanese populace at large. Unfortunately, such a shift in thinking won’t come easily to a nation whose Middle East policy is stuck in the past.

https://newlinesmag.com/essays/1950s-u-s-foreign-policy-looms-large-in-lebanon/

Photograph of Eisenhower, by Richard Avedon: http://theworldofphotographers.wordpress.com/2011/04/25/3385/dwight-david-eisenhower-richard-avedon/ or http://bit.ly/lDR0hN or http://tinyurl.com/6b24aja

Photograph of Beirut grain silos after the explosion of August 04, 2020, by Emmanuel Durand: https://hiddenarchitecture.net/beirut-grain-silos/