This sermon was Dr. Fosdick’s Armistice Day (now Veterans Day) sermon in 1933. After recalling his support for the First World War, Fosdick renounces war and pledges that never again will he support or sanction another, a pledge he kept during World War II.

This sermon was Dr. Fosdick’s Armistice Day (now Veterans Day) sermon in 1933. After recalling his support for the First World War, Fosdick renounces war and pledges that never again will he support or sanction another, a pledge he kept during World War II.

A few years ago my father told me about it, about how powerful it was, and about some brief correspondence he shared with Dr. Fosdick 60 years ago. The Riverside Church graciously sent me a transcript of the sermon and I have tried to faithfully transcribe it here. I daresay such heresy is now nowhere to be found near the bleached, sanitized, fundamentalized environs of 2000 Broadus, Fort Worth, Texas. Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary is poorer for it.

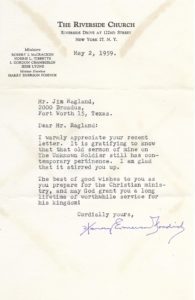

Two weeks ago, my father called to tell me he had found the long-lost letter! He flew here and brought it with him. I have today scanned the letter and its envelope and added them to this introduction.

Monsieur Jacques d’Nalgar, Vendredi 6 septembre 2019 de l’ère commune

…

Dr. Harry Emerson Fosdick

Preached at The Riverside Church, NYC

November 12, 1933

…

IT WAS AN interesting idea to deposit the body of an unrecognized soldier in the national memorial of the Great War, and yet, when one stops to think of it, how strange it is! Yesterday, in Rome, Paris, London, Washington, and how many capitals beside, the most stirring military pageantry, decked with flags and exultant with music, centered about the bodies of unknown soldiers. That is strange. So this is the outcome of Western civilization, which for nearly two thousand years has worshiped Christ, and in which democracy and science have had their widest opportunity — the whole nation pauses, its acclamations rise, its colorful pageantry centers, its patriotic oratory flourishes, around the unrecognizable body of a soldier blown to bits on the battlefield. That is strange.

It was the warlords themselves who picked him out as the symbol of war. So be it! As a symbol of war we accept him from their hands.

You may say that I, being a Christian minister, did not know him. I knew him well. From the north of Scotland, where they planted the sea with mines, to the trenches of France, I lived with him and his fellows — British, Australian, New Zealander, French, American. The places where he fought, from Ypres through the Somme battlefield to the southern trenches, I saw while he still was there. I lived with him in his dugouts in the trenches, and on destroyers searching for submarines off the shores of France. Short of actual battle, from training camp to hospital, from the fleet to no-man’s-land, I, a Christian minister, saw the war. Moreover I, a Christian minister, participated in it. I, too, was persuaded that it was a war to end war. I, too, was a gullible fool and thought that modern war could somehow make the world safe for democracy. They sent men like me to explain to the army the high meanings of war and, by every argument we could command, to strengthen their morale. I wonder if I ever spoke to the Unknown Soldier.

One night, in a ruined barn behind the lines, I spoke at sunset to a company of hand-grenaders who were going out that night to raid the German trenches. They told me that on the average no more than half a company came back from such a raid, and I, a minister of Christ, tried to nerve them for their suicidal and murderous endeavor. I wonder if the Unknown Soldier was in that barn that night.

Once in a dugout, which in other days had been a French wine cellar, I bade Godspeed at two in the morning to a detail of men going out on patrol in no-man’s-land. They were a fine company of American boys fresh from home. I recall that, huddled in the dark, underground chamber, they sang:

Lead, kindly Light, amid th’encircling gloom,

Lead thou me on;

The night is dark, and I am far from home;

Lead thou me on.

Then, with my admonitions in their ears, they went down from the second- to the first-line trenches and so out to no-man’s-land. I wonder if the Unknown Soldier was in that dugout.

You here this morning may listen to the rest of this sermon or not, as you please. It makes much less difference to me than usual what you do or think. I have an account to settle in this pulpit today between my soul and the Unknown Soldier.

He is not so utterly unknown as we sometimes think. Of one thing we can be certain: he was sound of mind and body. We made sure of that. All primitive gods who demanded bloody sacrifices on their altars insisted that the animals should be of the best, without mar or hurt. Turn to the Old Testament and you will find it written there: “Whether male or female, he shall offer it without blemish before the Lord.” The god of war still maintains the old demand. These men to be sacrificed upon his altars were sound and strong. Once there might have been guessing about that. Not now. Now we have medical science, which tests the prospective soldier’s body. Now we have psychiatry, which tests his mind. We used them both to make sure that these sacrifices for the god of war were without blemish. Of all insane and suicidal procedures, can you imagine anything madder than this, that all the nations should pick out their best, use their scientific skill to make certain that they are the best, and then in one mighty holocaust offer ten million of them on the battlefields of one war?

I have an account to settle between my soul and the Unknown Soldier. I deceived him. I deceived myself first, unwittingly, and then I deceived him, assuring him that good consequence could come out of that. As a matter of hardheaded, biological fact, what good can come out of that? Mad civilization, you cannot sacrifice on bloody altars the best of your breed and expect anything to compensate for the loss.

Of another thing we may be fairly sure concerning the Unknown Soldier — that he was a conscript. He may have been a volunteer but on actuarial average he probably was a conscript. The long arm of the nation reached into his home, touched him on the shoulder, saying, You must go to France and fight. If someone asks why in this “land of the free” conscription was used, the answer is, of course, that it was necessary if we were to win the war. Certainly it was. And that reveals something terrific about modern war. We cannot get soldiers — not enough of them, not the right kind of them — without forcing them. When a nation goes to war now, the entire nation must go. That means that the youth of the nation must be compelled, coerced, conscripted to fight.

When you stand before the tomb of the Unknown Soldier on some occasion, let us say when the panoply of military glory decks it with music and color, are you thrilled? I am not — not any more. I see there the memorial of one of the saddest things in American history, from the continued repetition of which may God deliver us — the conscripted boy!

He was a son, the hope of the family, and the nation coerced him. He was, perchance, a lover and the deepest emotion of his life was not desire for military glory or hatred of another country or any other idiotic thing like that, but love of a girl and hope of a home. He was, maybe, a husband and a father, and already, by that slow and beautiful gradation which all fathers know, he had felt the deep ambitions of his heart being transferred from himself to his children. And the nation coerced him. I am not blaming him; he was conscripted. I am not blaming the nation; it never could have won the war without conscription. I am simply saying that that is modern war, not by accident but by necessity, and with every repetition it will be more and more the attribute of war.

Last time they coerced our sons. Next time, of course, they will coerce our daughters, and in any future war they will absolutely conscript all property. Some old-fashioned Americans, born out of the long tradition of liberty, have trouble with these new coercions used as shortcuts to get things done, but nothing else compares with this inevitable, universal, national conscription in time of war. Repeated once or twice more, it will end everything in this nation that remotely approaches liberty.

If I blame anybody about this matter, it is men like myself who ought to have known better. We went out to the army and explained to these valiant men what a resplendent future they were preparing for their children by their heroic sacrifice. 0 Unknown Soldier, however can I make that right with you? For sometimes I think I hear you asking me about it:

Where is this great, new era that the war was to create? Where is it? They blew out my eyes in the Argonne. Is it because of that that now from Arlington I strain them vainly to see the great gains of the war? If I could see the prosperity, plenty, and peace of my children for which this mangled body was laid down!

My friends, sometimes I do not want to believe in immortality. Sometimes I hope that the Unknown Soldier will never know.

Many of you here knew these men better, you may think, than I knew them, and already you may be replacing my presentation of the case by another picture. Probably, you say, the Unknown Soldier enjoyed soldiering and had a thrilling time in France. The Great War, you say, was the most exciting episode of our time. Some of us found in it emotional release unknown before or since. We escaped from ourselves. We were carried out of ourselves. Multitudes were picked up from a dull routine, lifted out of the drudgery of common days with which they were infinitely bored, and plunged into an exciting adventure that they remember yet as the most thrilling episode of their careers.

Indeed, you say, how could martial music be so stirring and martial poetry so exultant if there were not at the heart of war a lyric glory? Even in the churches you sing,

Onward, Christian soldiers,

Marching as to war.

You, too, when you wish to express or arouse ardor and courage, use war’s symbolism. The Unknown Soldier, sound in mind and body — yes! The Unknown Soldier a conscript — probably! But be fair and add that the Unknown Soldier had a thrilling time in France.

To be sure, he may have had. Listen to this from a wounded American after a battle. “We went over the parapet at five o’clock and I was not hit till nine. They were the greatest four hours of my life.” Quite so! Only let me talk to you a moment about that. That was the first time he went over the parapet. Anything risky, dangerous, tried for the first time, well handled, and now escaped from, is thrilling to an excitable and courageous soul. What about the second time and the third time and the fourth? What about the dreadful times between, the long-drawn-out, monotonous, dreary, muddy barrenness of war, concerning which one who knew said “Nine-tenths of war is waiting?” The trouble with much familiar talk about the lyric glory of war is that it comes from people who never saw any soldiers except the American troops, fresh, resilient, who had time to go over the parapet about once. You ought to have seen the hardening-up camps of the armies which had been at the business since 1914. Did you ever see them? Did you look, as I have looked, into the faces of young men who had been over the top, wounded, hospitalized, hardened up — four times, five times, six times? Never talk to a man who has seen that about the lyric glory of war.

Where does all this talk about the glory of war come from, anyway?

Charge, Chester, charge! On, Stanley, on!”

Were the last words of Marmion.

That is Sir Walter Scott. Did he ever see war? Never.

And how can man die better

Than facing fearful odds,

For the ashes of his fathers,

And the temples of his gods?

That is Macaulay. Did he ever see war? He was never near one.

Storm ‘d at with shot and shell,

Boldly they rode and well,

Into the jaws of Death,

Into the mouth of Hell

Rode the six hundred.

That is Tennyson. Did he ever see war? I should say not.

There is where the glory of war comes from. We have heard very little about it from the real soldiers of this last war. We have had from them the appalling opposite. They say what George Washington said: it is “a plague to mankind.” The glory of war comes from poets, preachers, orators, the writers of martial music, statesmen preparing flowery proclamations for the people, who dress up war for other men to fight. They do not go to the trenches. They do not go over the top again and again and again.

Do you think that the Unknown Soldier would really believe in the lyric glory of war? I dare you; go down to Arlington National Cemetery and tell him that now.

Nevertheless, some may say that while war is a grim and murderous business with no glory in it in the end, and while the Unknown Soldier doubtless knew that well, we have the right in our imagination to make him the symbol of whatever was the most idealistic and courageous in the men who went out to fight. Of course we have. Now, let us do that! On the body of a French sergeant killed in battle was found a letter to his parents in which he said, “You know how I made the sacrifice of my life before leaving.” So we think of our Unknown Soldier as an idealist, rising up in answer to a human call and making the sacrifice of his life before leaving. His country seemed to him like Christ himself, saying, “If any man will come after me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross daily, and follow me.” Far from appealing to his worst, the war brought out the best — his loyalty, his courage, his venturesomeness, his care for the downtrodden, his capacity for self-sacrifice. The noblest qualities of his young manhood were aroused. He went out to France a flaming patriot, and in secret quoted Rupert Brooke to his own soul:

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England.

There, you say, is the Unknown Soldier.

Yes indeed, did you suppose I never had met him? I talked with him many a time. When the words that I would speak about war are a blistering fury on my lips and the encouragement I gave to war is a deep self-condemnation in my heart, it is of that I think. For I watched war lay its hands on these strongest, loveliest things in men and use the noblest attributes of the human spirit for what ungodly deeds! Is there anything more infernal than this, to take the best that is in man and use it to do what war does? This is the ultimate description of war — it is the prostitution of the noblest powers of the human soul to the most dastardly deeds, the most abysmal cruelties of which our human nature is capable. That is war.

Granted, then, that the Unknown Soldier should be to us a symbol of everything most idealistic in a valiant warrior, I beg of you, be realistic and follow through what war made the Unknown Soldier do with his idealism. Here is one eyewitness speaking:

Last night, at an officers’ mess there was great laughter at the story of one of our men who had spent his last cartridge in defending an attack, “Hand me down your spade, Mike,” he said; and as six Germans came one by one round the end of a traverse, he split each man’s skull open with a deadly blow.

The war made the Unknown Soldier do that with his idealism.

“I can remember,” says one infantry officer, “a pair of hands (nationality unknown) which protruded from the soaked ashen soil like the roots of a tree turned upside down; one hand seemed to be pointing at the sky with an accusing gesture. . . . Floating on the surface of the flooded trench was the mask of a human face which had detached itself from the skull.” War harnessed the idealism of the Unknown Soldier to that.

Do I not have an account to settle between my soul and him? They sent men like me into the camps to awaken his idealism, to touch those secret, holy springs within him so that with devotion, fidelity, loyalty, and self-sacrifice he might go out to war. 0 war, I hate you most of all for this, that you do lay your hands on the noblest elements in human character, with which we might make a heaven on earth, and you use them to make a hell on earth instead. You take even our science, the fruit of our dedicated intelligence, by means of which we might build here the City of God, and, using it, you fill the earth instead with new ways of slaughtering men. You take our loyalty, our unselfishness, with which we might make the earth beautiful, and, using these, our finest qualities, you make death fall from the sky and burst up from the sea and hurtle from unseen ambuscades sixty miles away; you blast fathers in the trenches with gas while you are starving their children at home by blockades; and you so bedevil the world that fifteen years after the Armistice we cannot be sure who won the war, so sunk in the same disaster are victors and vanquished alike. If war were fought simply with evil things, like hate, it would be bad enough, but when one sees the deeds of war done with the loveliest faculties of the human spirit, he looks into the very pit of hell.

Suppose one thing more — that the Unknown Soldier was a Christian. Maybe he was not, but suppose he was, a Christian like Sergeant York, who at the beginning intended to take Jesus so seriously as to refuse to fight but afterward, otherwise persuaded, made a real soldier. For these Christians do make soldiers. Religion is a force. When religious faith supports war, when, as in the Crusades, the priests of Christ cry, “Deus Vult” — God wills it — and, confirming ordinary motives, the dynamic of Christian devotion is added, then an incalculable resource of confidence and power is released. No wonder the war department wanted the churches behind them!

Suppose, then, that the Unknown Soldier was a Christian. I wonder what he thinks about war now. Practically all modern books about war emphasize the newness of it — new weapons, new horrors, new extensiveness. At times, however, it seems to me that still the worst things about war are the ancient elements. In the Bible we read terrible passages where the Hebrews thought they had a command from Jehovah to slaughter the Amalekites, “both man and woman, infant and suckling, ox and sheep, camel and ass.” Dreadful, we say — an ancient and appalling idea! Ancient? Appalling? Upon the contrary, that is war, and always will be. A military order, issued in our generation by an American general in the Philippines and publicly acknowledged by his counsel afterwards in a military court, commanded his soldiers to burn and kill, to exterminate all capable of bearing arms, and to make the island of Samar a howling wilderness. Moreover, his counsel acknowledged that he had given instructions to kill everyone over the age of ten. Far from launching into a denunciation of that American general, I am much more tempted to state his case for him. Why not? Cannot boys and girls of eleven fire a gun? Why not kill everything over ten? That is war, past, present and future. All that our modern fashions have done is to make the necessity of slaughtering children not the comparatively simple and harmless matter of shooting some of them in Samar, one by one, but the wholesale destruction of children, starving them by millions, impoverishing them, spoiling the chances of unborn generations of them, as in the Great War.

My friends, I am not trying to make you sentimental about this. I want you to be hardhearted. We can have this monstrous thing or we can have Christ, but we cannot have both. 0 my country, stay out of war! Cooperate with the nations in every movement that has any hope for peace; enter the World Court, support the League of Nations, contend undiscourageably for disarmament, but set your face steadfastly and forever against being drawn into another war. 0 church of Christ, stay out of war! Withdraw from every alliance that maintains or encourages it. It was not a pacifist, it was Field-Marshal Earl Haig who said, “It is the business of the churches to make my business impossible.” And 0 my soul, stay out of war!

At any rate, I will myself do the best I can to settle my account with the Unknown Soldier. I renounce war. I renounce war because of what it does to our own men. I have watched them come in gassed from the front-line trenches. I have seen the long, long hospital trains filled with their mutilated bodies. I have heard the cries of the crazed and the prayers of those who wanted to die and could not, and I remember the maimed and ruined men for whom the war is not yet over. I renounce war because of what it compels us to do to our enemies, bombing their mothers and villages, starving their children by blockades, laughing over our coffee cups about every damnable thing we have been able to do to them. I renounce war for its consequences, for the lies it lives on and propagates, for the undying hatreds it arouses, for the dictatorships it puts in the place of democracy, for the starvation that stalks after it. I renounce war and never again, directly or indirectly, will I sanction or support another! 0 Unknown Soldier, in penitent reparation I make you that pledge.

November 12, 1933

2 comments

2 pings

Until about an hour ago, I had not heard of Dr Fosdick! Then I heard how he was an advocate for peace – having being in the army in WWI – and an advocate for war; something he regretted. Then I looked at Project Gutenberg which had one of Dr Fosdick’s books. I searched under “war” inside it. His thinking is so clear. He explains that the arms manufacturers produce the weapons of war for profit. Then, the government that buys the weapons sends youngsters to the battle field to use these weapons telling them it is there patriotic duty. So why doesn’t the government tell the arms suppliers to do so out of duty and not for profit?

I carried on doing more Googling and heard about this speech and was so delighted and impressed with your site, that it has a copy of the 1933 speech and the beautiful story your contributor gave behind it – including the photos of the letter.

Thank you so much for posting it. Best wishes, Paul, UK

Author

Hello Paul in the UK. I first heard about this sermon from my father (see the most recent “obituary” post). He told me Harry Emerson Fosdick was openly hated by American fundamentalists. This was in the days before television, but radio broadcasts were full of broadsides against Fosdick. If that sort of thing interests you, Fosdick’s sermon “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?” is a must-read. If your interests lie in antiwar sentiment, look for the posts by Mark Twain, from the first volume of his autobiography, withheld until 50 years after his death. “Breaking News” is one, but there are others in that section. Also, check out my own effort at guerilla art: “Feliz Navidad” was first published on another website and during the winter solstice I added animated twinkling lights to the grim panorama. Unfortunately they did not convey when I moved the mural to Levantium.

All the best – I’m glad you’ve enjoyed visiting Levantium. Monsieur Jacques d’Nalgar (I maintain a modicum of a pseudonym because, when employed, it afforded a degree of plausible deniability. I have maintained that façade now that the USA is once again waltzing with fascism.)

[…] Y’all should read H.E. Fosdick’s Armistice Day sermon from 1933. It’s by any measure a classic and probably one of the best sermons of the 20th […]

[…] The Unknown Soldier […]