Eddy and the Mideast

Joseph C. GouldenOP-ED:

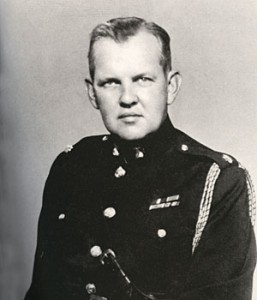

Middle East veterans of a certain era – the World War II era into the 1950s – speak with respectful awe of William A. Eddy. Soldier, scholar, statesman, spy, Arabist – of him a colleague said, “Bill Eddy was probably the nearest thing that the United States has had to a Lawrence of Arabia.”

His rich career is detailed by Thomas Lippman in “Arabian Knight: Colonel Bill Eddy USMC and the Rise of American Power in the Middle East.” Mr. Lippman reported from the Middle East for decades, chiefly with The Washington Post. He documents how Mr. Eddy initially exerted much influence on U.S. policy in the Middle East and how much of his advice went unheeded.

Born of missionary parents in 1896 in Sidon, in what is now Lebanon, Mr. Eddy learned Arabic as a child. After graduation from Princeton in 1917, he served in the Marine Corps in France during World War I, was severely wounded at the battle of Chateau Thierry, and was near death from pneumonia when he was sent home. He was awarded the Navy Cross and the Silver Star. After the war, he studied and taught in Cairo (where he introduced the game of basketball to the people of the Nile Valley), went on to earn a PhD in English Literature from Princeton in 1922, chaired the English Department at Dartmouth, and then became President of Hobart College just before the outbreak of World War II.

Col. Eddy returned to the Marines as war neared, quickly switched to the Office of Strategic Services and was sent to North Africa to do political spadework for the Allied invasion from a post as Naval Attache in Tangiers. He thrived on espionage. Germans bribed a telephone operator in his hotel to monitor his calls. The operator took the money, then told Eddy, who wrote his daughter, “We are taking the francs and composing fake conversations for him to report to them, conversations which should give the Germans plenty of phony information.”

Next came the seminal assignment of Eddy’s career: establishing relations with Ibn Saud, the king of Saudi Arabia, an impoverished backwater considered to be insignificant. But President Roosevelt sensed Saudi Arabia’s future importance as a source of oil, and as a U.S. toehold in the Middle East. FDR dispatched Col. Eddy there as “Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary.” Mr. Eddy wore Arab garb for his first meeting with the king and charmed him with his knowledge of and sympathy for the nation’s culture.

FDR’s fear was that insolvency would drive the kingdom back into the British sphere, with the United States excluded from oil concessions. So Eddy negotiated loans for agricultural and other development, to be repaid with oil. King Saud was favorably disposed to the United States because he was determined that “his country will not become a ward or a mere instrument for profit for some foreign government.” As Eddy (and a few others) felt, “the Arab people, as they gained independence, would face a choice of external loyalties and that it would be far preferable for them to align themselves with the United States than with the looming great rival, the Soviet Union.”

But friendship had limits. Ibn Saud refused American military advisers. He accepted U.S. technology, but laid down a rule: “We will use your iron, but leave our faith alone.” Traditions such as the veiling of women were none of the Americans’ business. He agreed to accept an airfield – but the Saudi flag flew over it, not the Stars and Stripes. During that period, Eddy also opened U.S. relations with Yemen.

At war’s end, Eddy left the Marines and plunged into the fierce war over creation of the U.S. intelligence establishment. He spoke for the State Department in negotiations over creation of the CIA and eventually ran the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research, but resigned from the State Department in 1947 over President Truman’s decision to support the creation of a new Jewish state in Palestine.

Col. Eddy felt strongly that the United States should form a “moral alliance” with Islam. As Mr. Lippman writes, “To support instead what Arabs saw as the expansionist, usurper state created by the Zionists in Palestine would bring down upon America the relentless rage of militant Islam. In this, he was the Cassandra of the Middle East.” Eddy correctly forecast that the U.S. alliance with Israel would inflame the Muslim world.

Eddy returned to the Middle East as a “consultant” to ARAMCO, which U.S. oil companies owned in conjunction with the Saudis. As Mr. Lippman writes, although Eddy was not on the U.S. government payroll, “throughout his years with ARAMCO he reported regularly to the CIA, where he had been present at the creation, and was a trusted informant, about Arab politics and personalities.” Eddy’s nephew, Ray Close, a longtime CIA officer, told Mr. Lippman, “He never spent five minutes in Washington as a member of the staff of the agency. He was a friend of [Allen] Dulles’s on a personal basis.”

Generally I dismiss “what if?” scenarios as a waste of time. But reading Eddy’s dire predictions on U.S. policy inescapably brought those two words to mind.

Joseph C. Goulden is writing a book on Cold War intelligence.

Oct 28 2008

My mother’s kid brother

Permanent link to this article: https://levantium.com/2008/10/28/my-mothers-kid-brother/