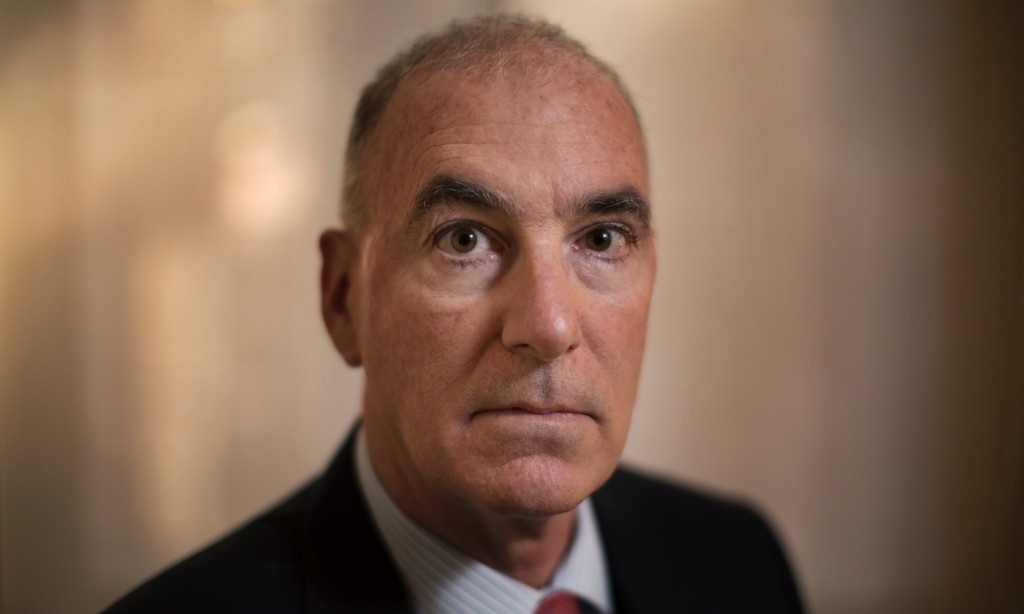

General Dan Bolger says what the US does not want to hear: Why We Lost

By Spencer Ackerman, Monday 10 November 2014 00.01 EST

Dan Bolger is not looking to add to the debate over the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. The retired three-star army general, out of patience with unresolved conflicts, means to end it.

On Tuesday, Bolger will publish his 500-page attempt to make sense of both the wars in which he served. Its blunt title pre-emptively maneuvers conversation over the book on to Bolger’s terrain: Why We Lost.

Senior army officers tend not to use the “L” word, certainly not in public, despite one war stretching into its 14th inconclusive year and the other one restarting. Bolger is not used to being out of step with the army. A tall man who speaks deliberately, he is respected in military circles for being a historian as well as an officer. Bolger deadpanned during an hour-long interview with the Guardian that he won’t get any more Christmas cards from his old friends in uniform.

But Bolger considers a reckoning with the military’s poor record in Iraq and Afghanistan overdue. The army in which he soldiered for three decades comes in for the greatest amount of blame, a decision that flatters the military’s pretensions about being above politics but arguably lets the Bush and Obama administrations off the hook. Bolger, a senior officer responsible for training the Iraqi and Afghan militaries, includes himself in the roster of failed generals.

“Here’s one I would offer that should be asked of every serving general and admiral: general, admiral, did we win? If we won, how are we doing now in the war against Isis? You just can’t get an answer to that question, and in fact, you don’t even hear it,” Bolger said.

“So if you can’t even say if you won or lost the stuff you just wrapped up, what the hell are you doing going into another one?”

Bolger has several explanations for why the US lost. The post-Vietnam army was built, deliberately, for short, conventional, decisive conflicts, yet the post-9/11 military leadership embraced – sometimes deliberately, sometimes through miscalculation – fighting insurgents and terrorists who knew the terrain, the people and the culture better than the US ever would.

“Anybody who does work in foreign countries will tell you, if you want long-term success, you have to understand that culture. We didn’t even come close. We knew enough to get by,” Bolger said.

More controversially, Bolger laments that the US did not pull out of Afghanistan after ousting al-Qaida in late 2001 and out of Iraq after ousting Saddam in April 2003. Staying in each conflict as it deteriorated locked policymakers and officers into a pattern of escalation, with persistence substituting for success. No one in uniform of any influence argued for withdrawal, or even seriously considered it: the US military mantra of the age is to leave behind a division’s worth of advisers as insurance and expect them to resolve what a corps could not.

The objection, which proved contemporaneously persuasive, is that the US would leave a vacuum inviting greater dangerous instability. “It would be a mess, and you’d have the equivalent of Isis,” Bolger conceded.

“But guess what: we’re in that same mess right now after eight years, and we’re going to be in the same mess after 13 years in Afghanistan.” The difference, he said, is thousands of Americans dead; tens of thousands of Americans left with life-changing wounds; and untold hundreds of thousands of Iraqis and Afghans dead, injured, impoverished or radicalized.

“Moreover, you’d be doing a real counterinsurgency, where they’d have to win it. That’s what the mistake is here: to think that we could go into these countries and stabilize their villages and fix their government, that’s incredible, unless you take a colonial or imperial attitude and say, ‘I’m going to be here for 100 years, this is the British Raj, I’m never leaving,’” he said.

It is there that Bolger plants his flag in an interminable debate within the army about the wisdom of counterinsurgency. He savages its proponents, chiefly Generals David Petraeus and Stanley McChrystal, for overpromising and under-delivering in Iraq and then recycling the formula to brew a weaker tea in Afghanistan. It leads Bolger’s book to some dubious places, like comparing the pre-Petraeus Iraq commander George Casey to Ulysses S Grant, the savior of the union, even though Casey under-promised and under-delivered.

Some in military circles view Bolger’s book as the first shot of an internecine fight to purge the army of counterinsurgency, much as the post-Vietnam generation attempted. It is an uphill struggle. While many officers of Bolger’s generation share his views, the Iraq surge saw the greatest tactical results of either long war past the invasion phase. Repudiating it is difficult without conceding the futility of either conflict, as Bolger has done, which, for much of the contemporary military, is a psychological step too far.

John Nagl, a retired army lieutenant colonel and prominent counterinsurgency advocate, praised Bolger as a “smart, dedicated army officer” while rejecting his thesis.

“While I haven’t yet read his new book, I don’t agree with him that we lost, and find it hard to believe that he does,” Nagl said.

But if the wars succeeded, Bolger said, “how come two or three years later, everything’s a pile of crap?”

One of the reasons was an “unstated assumption” that undergirded the American construction of the Iraqi and Afghan militaries, supposedly the US ticket out of both wars.

Bolger, who led the training of Afghan soldiers and held a senior post training the Iraqis, said US trainers banked on being present alongside their foreign charges for decades, guaranteeing their performance and compensating for weaknesses.

“The thought was to leave a conventional division, Korean-type model and you’d be there for 40 or 50 years with a mutual defense treaty and all that kind of stuff. Hey, the Korean army in 1953 was not very good. It takes a generation to build a good army: you need to retrain leaders, you have to build a non-commissioned officer corps,” he said.

The anticipated length of the US training helps explain the immaturity of both forces. The collapse of entire divisions of the Iraqi military against the Isis advance this year sent shockwaves through Washington. The Afghans are judged to lack critical air support, medical evacuation, intelligence and other capabilities, which helps explain how 9,000 soldiers have died in two years, as a US general revealed last week.

Yet never has an administration official or senior military officer – to include Bolger – told the American people to expect a half-century stay in a hostile foreign country. Instead, officials vaguely discuss a “long war”, leaving the actual anticipated duration unstated, to say nothing of the price in money and blood.

Surveying the latest war against Isis, Bolger sees the same pattern repeating.

“Here’s what wasn’t said: we never had the discussion where we said, ‘Hey, Mr President, you realize you’re signing up for a 50-year commitment, or plus, in Afghanistan and Iraq. Where was that discussion? We talk about surges, but those are all short-fuse things. We’re still not having that.

“Has President Obama come to the American people and said, ‘By the way, this fight against Isis is going to last 30 or 40 years. You guys good with that?’”

http://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2014/nov/10/general-dan-bolger-iraq-afghanistan-why-we-lost or http://bit.ly/1uedUys

Photograph: The Guardian.

2 comments

There is a great book titled “ We are Soldiers Still “ Cowritten by General Hal Moore a highly decorated soldier who fought one of the first major battles in Vietnam. He was a great soldier and a wise man. It contains a very revealing quote by the general “ It was the wrong war, in the wrong place, against the wrong people “

Sometimes Our Generals get it right.

Author

Only not until after they retire…